The guillotine was solemnly burned in front of the statue of Voltaire, but it was replaced by the rifle.

Continuing The 1871 Paris Commune,

our selection from Histoire de la France contemporaine by Gabriel Hanotaux published in 1903. The selection is presented in six easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in The 1871 Paris Commune.

Time: 1871

Place: Paris

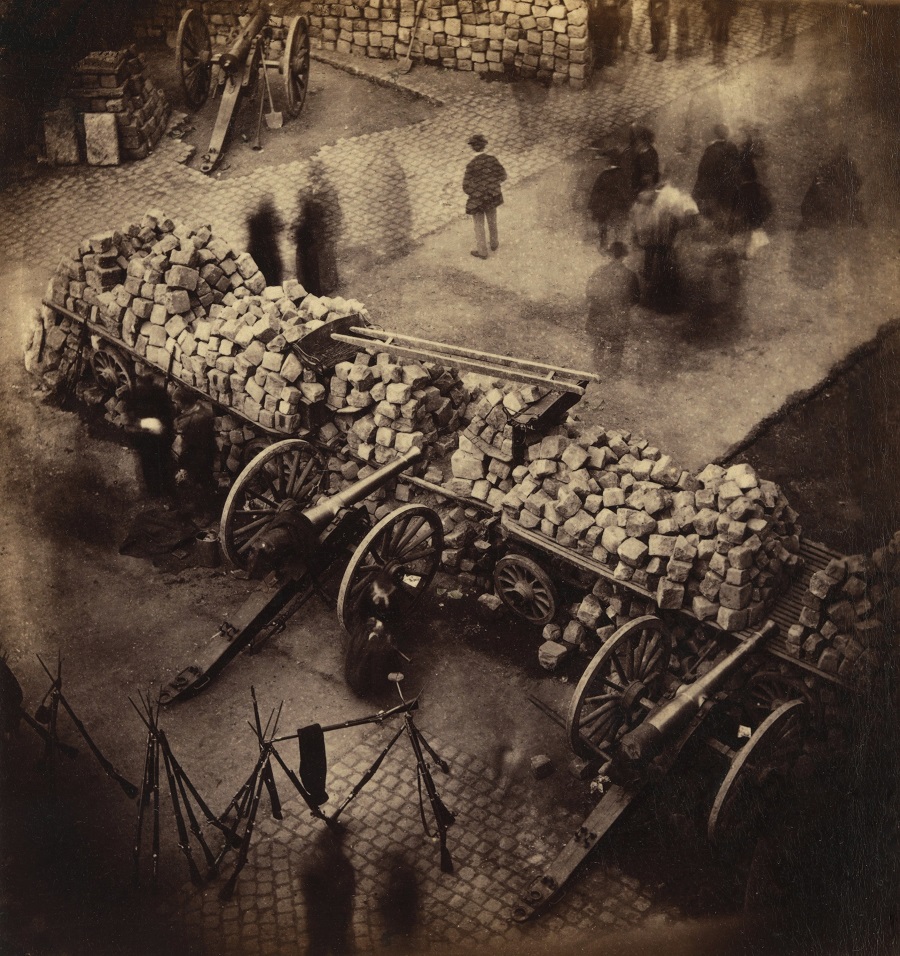

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

So then a new siege of Paris was to begin; the insurrection now became general, occupying the city and the forts on the south and west; M. Thiers and the National Assembly at Versailles; both parties under the eye of the German army, which, in conformity with the terms of the preliminaries, kept all the forts on the north and east.

Events hurried on with rigorous logic. Revolutionary measures multiplied. At the outset the Commune made some show of government; it maintained order in Paris up to a certain point and with some method in its deliberations. Something resembling that “gain of reason” attributed to it by Bismarck can be discovered in it. But it soon fell into clumsy imitation of the first revolution. The decree of hostages copied the list of suspects; the guillotine was suppressed, and then solemnly burned in front of the statue of Voltaire, but it was replaced by the rifle.

In default of practical reforms, the crowd was allowed free feeding for its antireligious violence; suppression of the public worship fund, separation of the Church from the State, arrest of the Archbishop of Paris, Monseigneur Darboy, of several members of the clergy, and Protestant congregations. Liberty of the press was effectively suppressed. Chaudey, deputy to the mayor of the First Ward, and a member of the International, was arrested at the office of the Siecle, of which he was editor.

Divisions, hatred, rose to fever-point among all these desperate men. Disorder, indiscipline, were everywhere. There was no longer any common understanding even for action, for self-defense. Rigault, a fellow with an insolent carriage, was like a madman unchained at the Prefecture of Police. In the end he was removed from his post; but, imitating Fouquier-Tinville, he got himself appointed Attorney-General to the Commune. Violence was only just arrested in front of the Bank of France, thanks to the energy of M. de Ploeuc, the relative moderation of the aged Beslay, and the coolness of Jourde, delegate of finance. For the rest, the Bank of France was in some sort paying its ransom by advancing (with the authority of the Government at Versailles) the money necessary for the pay of “thirty sous.”

Paris at length had opened her eyes. On April 18th, at the supplementary elections, in which eleven quarters were to take part, out of 280,000 electors on the register, only 53,000 took part in the voting; 205,000 abstained — that is to say, 80 percent. of the registered electors. Half the vacant seats were unfilled. Clément and Courbet belong to this day. Henceforth there was nothing but the most manifest tyranny in the great city.

On May 14th Fort Vanves was occupied. The circle drew closer. Delescluze, though dying, was everywhere; he tried to rouse the battalions, whose effectives were diminishing. On May 16th, at nightfall, the Vendome column was flung from its pedestal and shattered. The minority of twenty-two members separated from the majority. Soon it joined them again; on May 17th, at the Hotel de Ville, sixty-six members present still remained at the roll-call.

The forts being taken, the walls were on the point of yielding. It was necessary to think of the classic strife of insurrection, barricade-fighting. But the military men of the Commune — Cluseret, Rossel — infatuated with their ideas of the great war, had made no preparations. Men felt themselves taken by surprise. What was to be done? Then the idea of destruction, of annihilation of the town in the last hours of the catastrophe, began to haunt those fated brains. Delescluze and his colleagues of the Nineteenth Ward placarded: “After our barricades, our houses; after our houses, our ruins.” Valles wrote, “If M. Thiers is a chemist, he will understand us.”

An intense horror spread over the town, no longer knowing the nature of the awakening at hand. The population, which had let things take their course, was now reduced to shutting itself up in the houses. The National Guards ran hither and thither in the empty streets, with the stocks of their rifles forcing suspected houses or shops to open. Some timid efforts were distinguishable on the part of the National Guards to prepare resistance from the inside. M. Thiers received numerous suggestions, proposals of all kinds. One day a promise was made to deliver one of the gates of Paris to him. He spent the night with General Douay in the Bois de Boulogne, waiting for the signal that never came. Meanwhile he was informed that he would find a counter-movement all ready as soon as the troops crossed the lines of defense. Tricolor sleeve-badges were prepared. The great mass of the population waited in a state of terrible anxiety for the entrance of the regular troops.

The Commune felt that it was surrounded by enemies. It decided to draw up lists of suspects. Amouroux recalled that a law of hostages was in existence, and cried out, “Let us strike the priests!” Rigault, on the 19th, inaugurated the sittings of a jury on accusation. On all sides shooting began at the moment when – the terrible contact was on the point of taking place. The works of approach now permitted the bombardment of the gates of La Muette, Auteuil, Saint-Cloud, Point-du-Jour. The Fédérate troops, worn out by their ceaseless efforts, refused to serve. The breach was made; the wall, untenable under the projectiles, was abandoned. The assault was fixed for the 23rd.

On the 21st, toward three o’clock in the afternoon, a man appeared upon the ramparts near the Saint-Cloud gate and waved a white handkerchief. In spite of the projectiles, he insisted, he shouted. Captain Garnier, of the Engineers, on service in the trenches, drew near. The man declared that the gate and the wall were without defenders, and the troops could penetrate into the town without striking a blow. He gave his name. It was Ducatel, a foreman in the municipal service.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.