Today’s installment concludes The 1871 Paris Commune,

our selection from Histoire de la France contemporaine by Gabriel Hanotaux published in 1903.

If you have journeyed through the installments of this series so far, just one more to go and you will have completed a selection from the great works of six thousand words. Congratulations! For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in The 1871 Paris Commune.

Time: 1871

Place: Paris

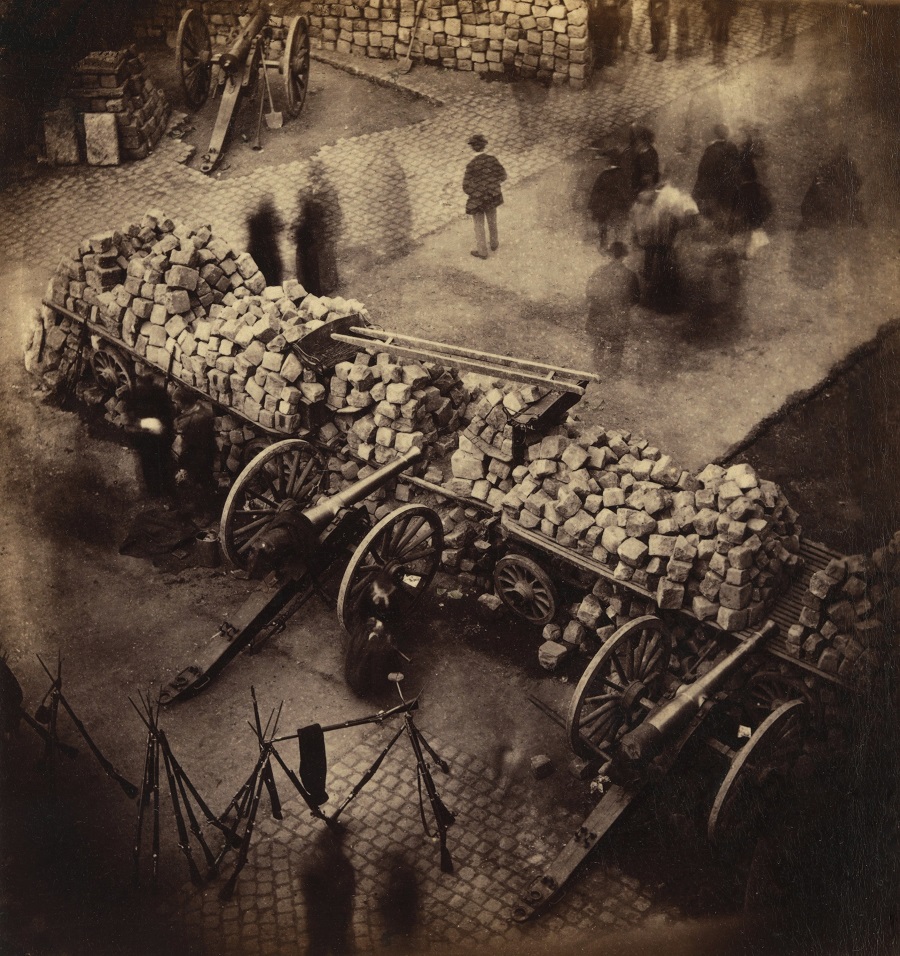

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

In the night, while the center of Paris was one immense furnace, the conflagration reached the quarters that were still being defended. Fire at the Chateau-d’Eau, fire at the Boulevard Voltaire, fire at the Grenier d’Abondance. The Seine, whose waters were already dyed with blood, rolled through Paris like a bed of fire; straws from the granary, papers from all the different records, made a rain of sparks; the air was scorching.

From Thursday, the 25th, there was a multiplication of executions. At the Saint-Sulpice Seminary an ambulance full of Fédérates, under the direction of Doctor Faneau, were slaughtered; it is said that some combatants had taken refuge here and had fired on the troops. Everywhere upon the barricades National Guards taken with arms in their hands were shot. The houses were entered and searched; everything that was suspicious, everything that seemed suspicious, was in danger. The soldiers, black with smoke, were the blind instruments of public vengeance — sometimes also of private grudges. They no longer knew what they were doing. Their chiefs did not always take account of the formal orders that had been given by Marshal MacMahon forbidding useless violence. Often, too, the officers tried in vain to restrain the fury of the exasperated troops. A National Guard’s jacket, trousers with red stripes, blackened hands, a shoulder appearing to be bruised by the rifle-stock, a pair of clumsy boots on the feet, a suspicious mien, age, figure, a word, a gesture, sufficed.

Courts-martial were opened at the Chatelet, at the Collège de France, at the Ecole Militaire, in several town halls. The prisoners, collected in crowds at all the points where resistance had been offered, and, one may say, over the whole city, were sent before these improvised tribunals, which proceeded to a summary classification. Whether in the streets, or even before these tribunals, how many premature executions were there? How many decisions equivalent to these executions?

On Friday, the 26th, the fighting was concentrated first at Belleville and the Place du Trône. At Belleville, at the town hall of the Eleventh Ward, the remnant of the Central Committee had resumed the direction of affairs along with Varlin. The command was entrusted to Hippolyte Parent. Ferré was carrying out to the very end the horrible mission he had imposed upon himself. After a hideous procession in the streets, which was but one long agony of death, forty-eight hostages — priests, policemen, Jesuit fathers — were massacred in the Rue Haxo. Toward evening, Jecker, the banker, was shot at Père la Chaise.

On the other side, at the Panthéon, Millière, who took sides only at the last moment, Millière, who had long intervened, Millière, upon whom fatality and perhaps an implacable hatred were weighing, Millière was shot on the steps of the Panthéon.

The Bastille yielded at two o’clock. La Villette was still holding out. Indescribable sufferings overwhelmed the exhausted combatants. The fighting was now centered in the extreme quarters, not far from the advanced guards of the German army, who looked on at this spectacle, impassive, contenting themselves with herding back the fugitives.

Fighting was still in progress on Saturday, the 27th. The weather was awful; the sky livid, first a fog, then torrents of rain. There was fighting at La Villette, fighting at Charonne, fighting at Belleville. The center of resistance was still the town hall of the Eleventh Ward, the Buttes Chaumont, and the Rue Haxo. Ranvier brought the last combatants up to the barricades. Ferré was leading a troop of prisoners of the line, whom he still purposed to shoot; they were delivered by the crowd. He went back to La Roquette to fetch fresh victims, but the three hundred men imprisoned there showed fight. Those alone perished who tried to escape, and soon Ferré fled as fast as his horse could gallop at the sound of “Here are the Versailles men.”

On Saturday evening two centers of resistance remained in the Eleventh and Twentieth wards. Five or six members of the Commune — Trinquet, Ferré, Varlin, Ranvier — still held out at Belleville. Some hundreds of the Fédérates threw themselves into Père la Chaise, to fight and die behind the tombs.

On Sunday, at four o’clock in the morning, Père la Chaise was carried after a short struggle. The two wings of the Versailles army, which had enveloped Paris, met at the Rue Haxo, where they captured thirty pieces of artillery from the Fédérates. The town hall of the Eleventh Ward was taken after a desperate resistance. The last groups of the Fédérates led by Varlin, Ferré, Gambon, wandered from the Twentieth Ward to the Rue Fontaine-au-Roi in the Eleventh. Louis Piat hoisted the white flag and surrendered with about sixty combatants. The last barricade was in the Rue Ramponneau. One single Fédérate was defending it; he escaped; the last shots were fired. By one o’clock all was over. The tricolor floated over the whole city. On the 29th the Fort of Vincennes, defended by three hundred seventy-five infantrymen, of whom twenty-four were officers, surrendered after vainly trying to negotiate with the Germans. In the evening nine officers were put to death in the ditches.

On Sunday at midday Marshal MacMahon caused to be posted a proclamation addressed to the inhabitants of Paris, saying: “The army of France has come to save you. Paris is delivered. Our soldiers carried at four o’clock the last positions held by the insurgents. Today the conflict is over, order is reestablished, work and safety will again come into being.”

| <—Previous | Master List |

This ends our series of passages on The 1871 Paris Commune by Gabriel Hanotaux from his book Histoire de la France contemporaine published in 1903. This blog features short and lengthy pieces on all aspects of our shared past. Here are selections from the great historians who may be forgotten (and whose work have fallen into public domain) as well as links to the most up-to-date developments in the field of history and of course, original material from yours truly, Jack Le Moine. – A little bit of everything historical is here.

More information on The 1871 Paris Commune here and here and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.