Early in the morning the people assembled in large bodies at the Hôtel de Ville; the tocsin sounded from all the churches; the drums beat to summon the citizens together, who formed themselves into different bands of volunteers.

Continuing Revolutionaries Storm Bastille,

our selection from The Life of Napoleon Bounoparte by William Hazlitt published in 1830. The selection is presented in seven easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Revolutionaries Storm Bastille.

Time: July 14, 1789

Place: Paris

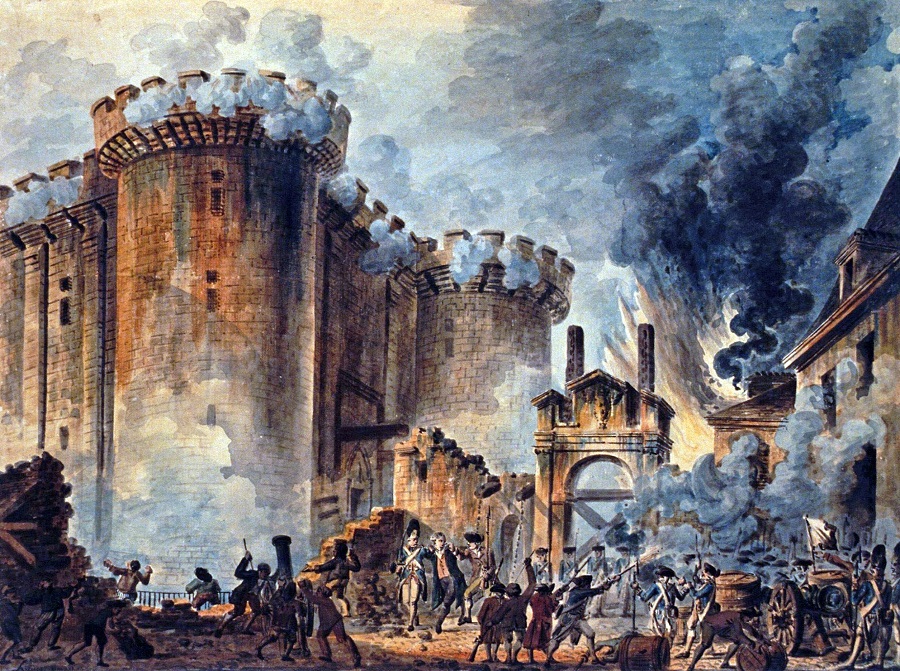

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

The defection of the French Guards, with the repugnance of the other troops to march against the capital, put a stop for the present to the projects of the Court. In the mean time the populace had assembled at the Hôtel de Ville, and loudly demanded the sounding of the tocsin and the arming of the citizens. Several highly respectable individuals also met here, and did much good in repressing a spirit of violence and mischief. They could not, however, effect everything. A number of disorderly people and of workmen out of employ, without food or place of abode, set fire to the barriers, infested the streets, and pillaged several houses in the night between the 12th and 13th.

The departure of Necker, which had excited such a sensation in the capital, produced as deep an impression at Versailles and on the Assembly, who manifested surprise and indignation, but not dejection. Lally Tollendal pronounced a formal eulogium on the exiled minister. After one or two displays of theatrical vehemence, which is inseparable from French enthusiasm and eloquence, they despatched a deputation to the King, informing him of the situation and troubles of Paris, and praying him to dismiss the troops and intrust the defence of the capital to the city militia. The deputation received an answer which amounted to a repulse. The Assembly now perceived that the designs of the Court party were irrevocably fixed, and that it had only itself to rely upon. It instantly voted the responsibility of the ministers and of all the advisers of the Crown, “of whatsoever rank or degree.”

This last clause was pointed at the Queen, whose influence was greatly dreaded. They then, from an apprehension that the doors might be closed during the night in order to dissolve the Assembly, declared their sittings permanent. A vice-president was chosen, to lessen the fatigue of the Archbishop of Vienne. The choice fell upon Lafayette. In this manner a part of the Assembly sat up all night. It passed without deliberation, the deputies remaining on their seats, silent, but calm and serene. What thoughts must have revolved through the minds of those present on this occasion! Patriotism and philosophy had here taken up their sanctuary. If we consider their situation; the hopes that filled their breasts; the trials they had to encounter; the future destiny of their country, of the world, which hung on their decision as in a balance; the bitter wrongs they were about to sweep away; the good they had it in their power to accomplish — the countenances of the Assembly must have been majestic, and radiant with the light that through them was about to dawn on ages yet unborn. They might foresee a struggle, the last convulsive efforts of pride and power to keep the world in its wonted subjection — but that was nothing — their final triumph over all opposition was assured in the eternal principles of justice and in their own unshaken devotedness to the great cause of mankind! If the result did not altogether correspond to the intentions of those firm and enlightened patriots who so nobly planned it, the fault was not in them, but in others.

At Paris the insurrection had taken a more decided turn. Early in the morning the people assembled in large bodies at the Hôtel de Ville; the tocsin sounded from all the churches; the drums beat to summon the citizens together, who formed themselves into different bands of volunteers. All that they wanted was arms. These, except a few at the gunsmiths’ shops, were not to be had. They then applied to M. de Flesselles, a provost of the city, who amused them with fair words. “My children,” he said, “I am your father!” This paternal style seems to have been the order of the day. A committee sat at the Hôtel de Ville to take measures for the public safety. Meanwhile a granary had been broken open: the Garde-Meuble had been ransacked for old arms; the armorers’ shops were plundered; all was a scene of confusion, and the utmost dismay everywhere prevailed. But no private mischief was done. It was a moment of popular frenzy, but one in which the public danger and the public good overruled every other consideration. The grain which had been seized, the carts loaded with provisions, with plate or furniture, and stopped at the barriers, were all taken to the Grève as a public depot.

The crowd incessantly repeated the cry for arms, and were pacified by an assurance that thirty thousand muskets would speedily arrive from Charleville. The Duc d’Aumont was invited to take the command of the popular troops; and on hesitating, the Marquis of Salle was nominated in his stead. The green cockade was exchanged for one of red and blue, the colors of the city. A quantity of powder was discovered, as it was about to be conveyed beyond the barriers; and the cases of fire-arms promised from Charleville turned out, on inspection, to be filled with old rags and logs of wood. The rage and impatience of the multitude now became extreme. Such perverse, trifling, and barefaced duplicity would be unaccountable anywhere else; but in France they pay with promises; and the provost, availing himself of the credulity of his audience, promised them still more arms at the Chartreux. To prevent a repetition of the excesses of the mob, Paris was illuminated at night and a patrol paraded the streets.

The following day, the people being deceived as to the convoy of arms that was to arrive from Charleville, and having been equally disappointed in those at the Chartreux, broke into the Hospital of Invalids, in spite of the troops stationed in the neighborhood, and carried off a prodigious number of stands of arms concealed in the cellars. An alarm had been spread in the night that the regiment quartered at St. Denis was on its way to Paris, and that the cannon of the Bastille had been pointed in the direction of the street of St. Antoine. This information, the dread which this fortress inspired, the recollection of the horrors which had been perpetrated there, its very name, which appalled all hearts and made the blood run cold, the necessity of wresting it from the hands of its old and feeble possessors, drew the attention of the multitude to this hated spot. From nine in the morning of the memorable July 14th, till two, Paris from one end to the other rang with the same watchword: “To the Bastille! To the Bastille!” The inhabitants poured there in throngs from all quarters, armed with different weapons; the crowd that already surrounded it was considerable; the sentinels were at their posts, and the drawbridges raised as in war-time.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.