The extreme severity of the Forest Laws was chiefly enforced to prevent the assemblage of Saxons in those vast wooded spaces.

Continuing Domesday Book Completed,

our selection from Popular History of England by Charles Knight published in 1860. The selection is presented in five easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Domesday Book Completed.

Time: 1086

Place: England

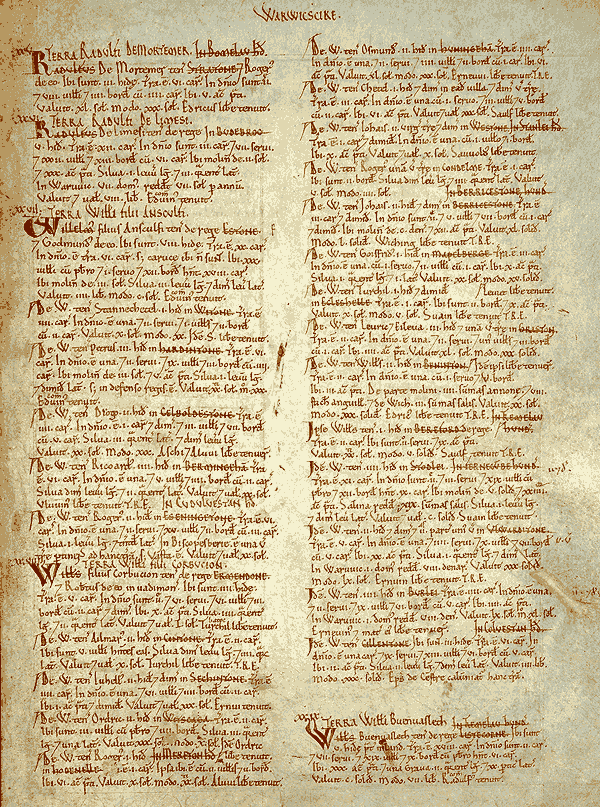

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

It is a curious fact that some woodland spots in the New Forest have still names with the terminations of ham and ton. There are many evidences of the former existence of human abodes in places now solitary; yet we doubt whether this part of the district plentifully supplied Winchester with food, as Ordericus relates; for it is a sterile district, in most places, fitted for little else than the growth of timber. The lower lands are marsh, and the upper are sand. The Conqueror, says the Saxon Chronicle, “so much loved the high deer as if he had been their father.” The first of the Norman kings, and his immediate successors, would not be very scrupulous about the depopulation of a district if the presence of men interfered with their pleasures. But Thierry thinks that the extreme severity of the Forest Laws was chiefly enforced to prevent the assemblage of Saxons in those vast wooded spaces which were now included in the royal demesnes.

All these extensive tracts were, more or less, retreats for the dispossessed and the discontented. The Normans, under pretense of preserving the stag and the hare, could tyrannize with a pretended legality over the dwellers in these secluded places; and thus William might have driven the Saxon people of Ytene to emigrate, and have destroyed their cottages, as much from a possible fear of their association as from his own love of “the high deer.” Whatever was the motive, there were devastation and misery. Domesday shows that in the district of the New Forest certain manors were afforested after the Conquest; cultivated portions, in which the Sabbath bell was heard. William of Jumièges, the Conqueror’s own chaplain, says, speaking of the deaths of Richard and Rufus: “There were many who held that the two sons of William the King perished by the judgment of God in these woods, since for the extension of the forest he had destroyed many inhabited places (villas) and churches within its circuit.” It appears that in the time of Edward the Confessor about seventeen thousand acres of this district had been afforested; but that the cultivated parts remaining had then an estimated value of three hundred and sixty-three pounds. After the afforestation by the Conqueror, the cultivated parts yielded only one hundred and twenty-nine pounds.

The grants of land to huntsmen (venatores) are common in Hampshire, as in other parts of England; and it appears to have been the duty of an especial officer to stall the deer — that is, to drive them with his troop of followers from all parts to the center of a circle, gradually contracting, where they were to stand for the onslaught of the hunters. In the survey many parks are enumerated. The word hay (haia), which is still found in some of our counties, meant an enclosed part of a wood to which the deer were driven.

In the seventeenth century this mode of hunting upon a large scale, by stalling the deer — this mimic war — was common in Scotland. Taylor, called the “Water Poet,” was present at such a gathering, and has described the scene with a minuteness which may help us to form a picture of the Norman hunters: “Five or six hundred men do rise early in the morning, and they do disperse themselves divers ways; and seven, eight, or ten miles’ compass, they do bring or chase in the deer in many herds — two, three, or four hundred in a herd — to such a place as the noblemen shall appoint them; then, when the day is come, the lords and gentlemen of their companies do ride or go to the said places, sometimes wading up to the middle through bourns and rivers; and then they being come to the place, do lie down on the ground till those foresaid scouts, which are called the ‘tinkhelt,’ do bring down the deer. Then, after we had stayed there three hours or thereabouts, we might perceive the deer appear on the hills round about us — their heads making a show like a wood — which being followed close by the tinkhelt, are chased down into the valley where we lay; then all the valley on each side being waylaid with a hundred couple of strong Irish greyhounds, they are let loose as occasion serves upon the herd of deer, that with dogs, guns, arrows, dirks, and daggers, in the space of two hours fourscore fat deer were slain.”

Domesday affords indubitable proof of the culture of the vine in England. There are thirty-eight entries of vineyards in the southern and eastern counties. Many gardens are enumerated. Mills are registered with great distinctness; for they were invariably the property of the lords of the manors, lay or ecclesiastical; and the tenants could only grind at the lord’s mill. Wherever we find a mill specified in Domesday, there we generally find a mill now. At Arundel, for example, we see what rent was paid by a mill; and there still stands at Arundel an old mill whose foundations might have been laid before the Conquest. Salt works are repeatedly mentioned. They were either works upon the coast for procuring marine salt by evaporation, or were established in the localities of inland salt springs. The salt works of Cheshire were the most numerous, and were called “wiches.” Hence the names of some places, such as Middlewich and Nantwich. The revenue from mines offers some curious facts. No mention of tin is to be found in Cornwall. The ravages of Saxon and Dane, and the constant state of hostility between races, had destroyed much of that mineral industry which existed in the Roman times. A century and a half after the Conquest had elapsed before the Norman kings had a revenue from the Cornish iron mines. Iron forges were registered, and lumps of hammered iron are stated to have been paid as rent. Lead works are found only upon the king’s demesne in Derbyshire.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.