He calmly finished his dinner, without saying a word of the order he had received, and immediately after got into his carriage with his wife and took the road to Brussels.

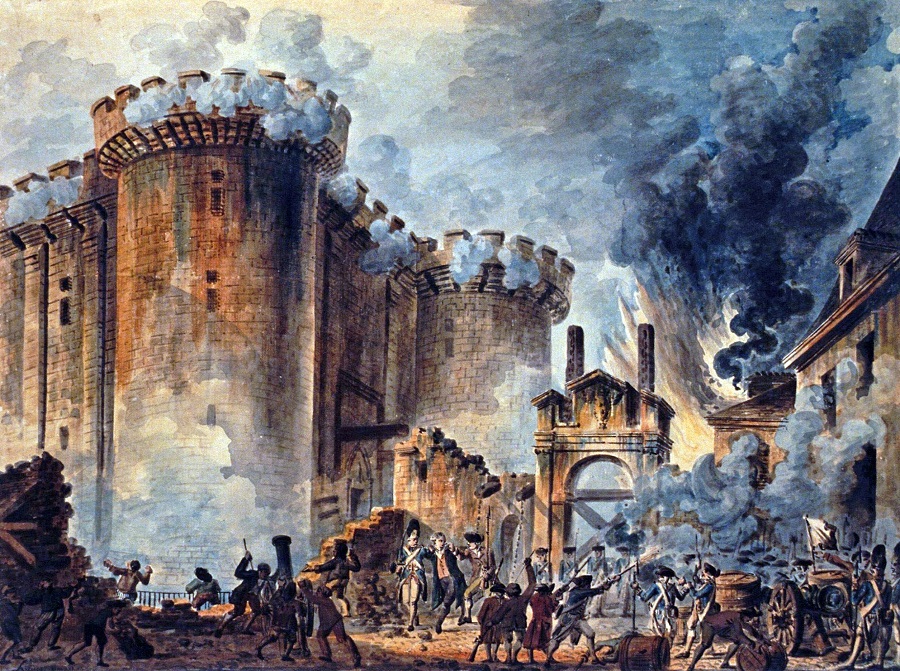

Continuing Revolutionaries Storm Bastille,

our selection from The Life of Napoleon Bounoparte by William Hazlitt published in 1830. The selection is presented in seven easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Revolutionaries Storm Bastille.

Time: July 14, 1789

Place: Paris

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

Paris was in a state of extreme agitation. This immense city was unanimous in its devotedness to the Assembly. A capital is at all times, and Paris was then more particularly, the natural focus of a revolution. To this many causes contribute. The actual presence of the monarch dissipates the illusions of royalty; and he is no longer, as in the distant province or petty village, an abstraction of power and majesty, another name for all that is great and exalted, but a common mortal, one man among a million of men, perhaps one of the meanest of his race. Pageants and spectacles may impose on the crowd; but a weak or haughty look undoes the effect, and leads to disadvantageous reflections on the title to or the good resulting from all this display of pomp and magnificence. From being the seat of the court, its vices are better known, its meannesses are more talked of. * In the number and distraction of passing objects and interests, the present occupies the mind alone — the chain of antiquity is broken, and custom loses its force. Men become “flies of a summer.” Opinion has here many ears, many tongues, and many hands to work with. The slightest whisper is rumored abroad, and the roar of the multitude breaks down the prison or the palace gates. They are seldom brought to act together but in extreme cases; nor is it extraordinary that, in such cases, the conduct of the people is violent, from the consciousness of transient power, its impatience of opposition, its unwieldy bulk and loose texture, which cannot be kept within nice bounds or stop at half-measure.

[* It was observed that almost all the greatest cruelties of the Reign of Terror were resolved on by committees of persons who had been in the immediate employment of the great, and had suffered by their caprice and insolence.]

Nothing could be more critical or striking than the situation of Paris at this moment. Everything betokened some great and decisive change. Foreign bayonets threatened the inhabitants from without, famine within. The capitalists dreaded a bankruptcy; the enlightened and patriotic the return of absolute power; the common people threw all the blame on the privileged classes. The press inflamed the public mind with innumerable pamphlets and invectives against the government, and the journals regularly reported the proceedings and debates of the Assembly. Everywhere in the open air, particularly in the Palais-Royal, groups were formed, where they read and harangued by turns. It was in consequence of a proposal made by one of the speakers in the Palais-Royal that the prison of the Abbaye was forced open and some grenadiers of the French Guards, who had been confined for refusing to fire upon the people, were set at liberty and led out in triumph.

Paris was in this state of excitement and apprehension when the Court, having first stationed a number of troops at Versailles, at Sèvres, at the Champ-de-Mars, and at St. Denis, commenced offensive measures by the complete change of all the ministers and by the banishment of Necker. The latter, on Saturday, July 11th, while he was at dinner, received a note from the King, enjoining him to quit the kingdom without a moment’s delay. He calmly finished his dinner, without saying a word of the order he had received, and immediately after got into his carriage with his wife and took the road to Brussels. The next morning the news of his disgrace reached Paris. The whole city was in a tumult: above ten thousand persons were, in a short time, collected in the garden of the Palais-Royal. A young man of the name of Camille Desmoulins, one of the habitual and most enthusiastic haranguers of the crowd, mounted on a table and cried out that “there was not a moment to lose; that the dismission of Necker was the signal for the St. Bartholomew of liberty; that the Swiss and German regiments would presently issue from the Champ-de-Mars to massacre the citizens; and that they had but one resource left, which was to resort to arms.” And the crowd, tearing each a green leaf, the color of hope, from the chestnut-trees in the garden, which were nearly laid bare, and wearing it as a badge, traversed the streets of Paris, with the busts of Necker and of the Duke of Orléans, who was also said to be arrested, covered with crape and borne in solemn pomp.

They had proceeded in this manner as far as the Place Vendôme, when they were met by a party of the Royal Allemand, whom they put to flight by pelting them with stones; but at the Place Louis XV they were assailed by the dragoons of the Prince of Lambesc; the bearer of one of the busts and a private of the French Guards were killed; the mob fled into the Garden of the Tuileries, whither the Prince followed them at the head of his dragoons, and attacked a number of persons who knew nothing of what was passing, and were walking quietly in the gardens. In the scuffle, an old man was wounded; the confusion as well as the resentment of the people became general; and there was but one cry, “To arms!” to be heard throughout the Tuileries, the Palais-Royal, in the city, and the suburbs.

The French Guards had been ordered to their quarters in the Chaussée-d’Antin, where sixty of Lambesc’s dragoons were posted opposite to watch them. A dispute arose, and it was with much difficulty they were prevented from coming to blows. But when the former learned that one of their comrades had been slain, their indignation could no longer be restrained; they rushed out, killed two of the foreign soldiers, wounded three others, and the rest were forced to fly. They then proceeded to the Place Louis XV, where they stationed themselves between the people and the troops and guarded this position the whole of the night. The soldiers in the Champ-de-Mars were then ordered to attack them, but refused to fire, and were remanded back to their quarters.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.