Today’s installment concludes Revolutionaries Storm Bastille,

our selection from The Life of Napoleon Bounoparte by William Hazlitt published in 1830.

If you have journeyed through the installments of this series so far, just one more to go and you will have completed a selection from the great works of seven thousand words. Congratulations! For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Revolutionaries Storm Bastille.

Time: July 14, 1789

Place: Paris

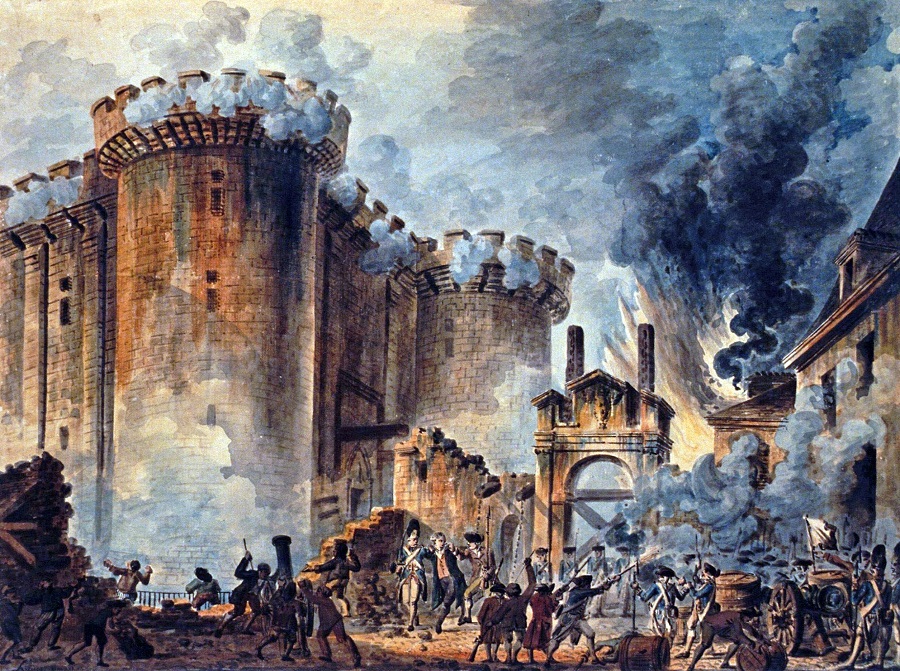

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

While all this was passing, and before it became known at Versailles, the Court was preparing to carry into effect its designs against the Assembly and the capital. The night between the 14th and 15th was fixed upon for their execution. The new minister, Breteuil, had promised to reestablish the royal authority within three days. Marshal Broglie, who commanded the army round Paris, was invested with unlimited powers. The Assembly, it was agreed upon, were to be dissolved, and forty thousand copies of a proclamation to this effect were ready to be circulated throughout the kingdom. The rising of the populace was supposed to be a temporary evil, and it was thought to the last moment an impossibility that a mob of citizens should resist an army. The Assembly was duly apprised of all these projects. It sat for two days in a state of constant inquietude and alarm. The news from Paris was doubtful. A firing of cannon was supposed to be heard, and persons anxiously placed their ears to the ground to listen. The escape of the King was also expected, as a carriage had been kept in readiness, and the bodyguard had not pulled off their boots for several days.

In the orangery belonging to the palace, meat and wine had been distributed among the foreign troops to encourage and spirit them up. The Viscount of Noailles and another deputy, Wimpfen, brought word of the latest events in the capital, and of the increasing violence of the people. Couriers were dispatched every half-hour to gather intelligence. Deputations waited on the King to lay before him the progress of the insurrection, but he still gave evasive and unsatisfactory answers. In the night of the 14th the Duke of Liancourt had informed Louis XVI of the taking of the Bastille and the massacre of the garrison on the preceding day. “It is a revolt!” exclaimed the monarch, taken by surprise. “No, sire, it is a revolution,” was the answer.

[The Bastille was taken about a quarter before six o’clock in the evening (Tuesday, July 14th), after a four-hours’ attack. Only one cannon was fired from the fortress, and only one person was killed among the besieged. The garrison consisted of 82 Invalids, 2 cannoneers, and 32 Swiss. Of the assailants, 83 were killed on the spot, 60 were wounded, of whom 15 died of their wounds, and 13 were disabled. A great many barrels of gunpowder had been conveyed here from the arsenal, in the night between the 12th and 13th. Delaunay, the governor, was killed on the steps of the Hôtel de Ville, as also Delosme, the mayor. Only seven prisoners were found in the Bastille; four of these, Pujade, Bechade, La Roche, and La Caurege, were for forgery. M. de Solages was put in in 1782, at the desire of his father, since which time every communication from without was carefully withheld from him. He did not know the smallest event that had taken place in all that time, and was told by the turnkey, when he heard the firing of the cannon, that it was owing to a riot about the price of bread. M. Tavernier, a bastard son of Paris Duverney, had been confined ever since August 4, 1759. The last prisoner was a Mr. White, who went mad, and it could never be discovered who or what he was: by the name he must have been English.

When Lord Albemarle was ambassador at Paris, in the year 1753, he by mere accident caught a sight of the list of persons confined in the Bastille, lying on the table of the French minister, with the name of Gordon at their head. Being struck with the circumstance, he inquired into the meaning of it; but the French minister could give no account of it; and on the prisoner himself being released and sent for, he could only state that he had been confined there thirty years, but had not the slightest knowledge or suspicion of the cause for which he had been arrested. Nor is this wonderful, when we consider that lettres de cachet were sold, with blanks left for the names to be filled up at the pleasure or malice of the purchasers.

If it was only to prevent the recurrence of one such instance (with the feeling in society at once shrinking from and tamely acquiescing in it), the Revolution was well purchased. When the crowd gained possession of this loathsome spot, they eagerly poured into every corner and turning of it, went down into the lowest dungeons with a breathless curiosity and horror, knocking with sledge-hammers at their triple portals, and breaking down and destroying everything in their way. The stones and devices on the battlements were torn off and thrown into the ditch, and the papers and documents were at the same time unfortunately destroyed.

A low range of dungeons was discovered underground, close to the moat; and so contrived that, if those within had forced a passage through, they would have let in the water of the ditch and been suffocated. In one of these a skeleton was found hanging to an iron cramp in the wall. In reading the accounts of the demolition of this building, one feels that indignation should have melted the stone walls like flax, and that the dungeons should have given up their dead to assist the living!

The Bastille was begun in 1370, in Charles V’s time, by one Hugh Abriot, provost of the city, who was afterward shut up in it in 1381. It at first consisted only of two towers: two more were added by Charles VI, and four more in 1383. Two days after it was taken, it was ordered by the National Assembly to be razed to the ground, and in May, 1790, not a trace of it was left. — ED.]

| <—Previous | Master List |

This ends our series of passages on Revolutionaries Storm Bastille by William Hazlitt from his book The Life of Napoleon Bounoparte published in 1830. This blog features short and lengthy pieces on all aspects of our shared past. Here are selections from the great historians who may be forgotten (and whose work have fallen into public domain) as well as links to the most up-to-date developments in the field of history and of course, original material from yours truly, Jack Le Moine. – A little bit of everything historical is here.

More information on Revolutionaries Storm Bastille here and here and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.