Today’s installment concludes Domesday Book Completed,

our selection from Popular History of England by Charles Knight published in 1860.

If you have journeyed through the installments of this series so far, just one more to go and you will have completed a selection from the great works of five thousand words. Congratulations! For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Domesday Book Completed.

Time: 1086

Place: England

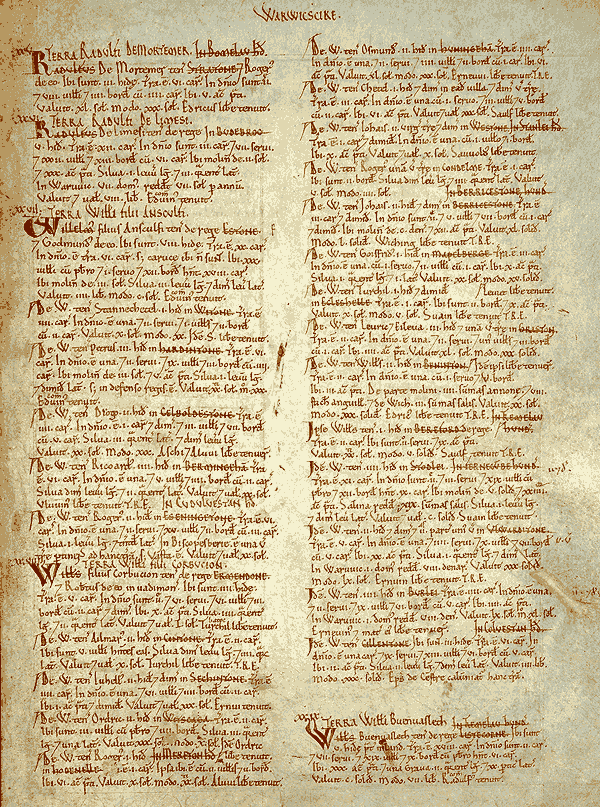

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

These words, “in fee, with right of inheritance,” leave no doubt that the great vassals of the crown were absolute proprietors, and that all their subvassals had the same right of holding in perpetuity. The estate, however, reverted to the crown if the race of the original feoffee became extinct, and in cases, also, of felony and treason. When Alain of Bretagne, who commanded the rear of the army at the battle of Hastings, and who had received four hundred and forty-two manors, bowed before the King at Salisbury, at the great council in 1085, and swore to be true to him against all manner of men, he also brought with him his principal land-sittende men (land-owners), who also bowed before the King and became his men. They had previously taken the oath of fealty to Alain of Bretagne, and engaged to perform all the customs and services due to him for their lands and tenements. Alain, and his men, were proprietors, but with very unequal rights. Alain, by his tenure, was bound to provide for the King as many armed horsemen as the vast extent of his estates demanded. But all those whom he had enfeoffed, or made proprietors, upon his four hundred and forty-two manors, were each bound to contribute a proportionate number. When the free service of forty days was to be enforced, the great earl had only to send round to his vassals, and the men were at his command.

By this organization, which was universal throughout the kingdom, sixty thousand cavalry could, with little delay, be called into the field. Those who held by this military service had their allotments divided into so many knights’ fees, and each knight’s fee was to furnish one mounted and armed soldier. The great vassals retained a portion of their land as their demesnes, having tenants who paid rents and performed services not military. But, under any circumstances, the vassal of the crown was bound to perform his whole free service with men and horses and arms. It is perfectly clear that this wonderful organization rendered the whole system of government one great confederacy, in which the small proprietors, tenants, and villeins had not a chance of independence; and that their condition could only be ameliorated by those gradual changes which result from a long intercourse between the strong and the weak, in which power relaxes its severity and becomes protection.

In the ordinance in which the King commanded “free service” he also says, “we will that all the freemen of the kingdom possess their lands in peace, free from all tallage and unjust exaction.” This, unhappily for the freemen, was little more than a theory under the Norman kings. There were various modes of making legal exaction the source of the grossest injustice. When the heir of an estate entered into possession he had to pay a “relief,” or heriot, to the lord. This soon became a source of oppression in the crown; and enormous sums were exacted from the great vassals. The lord was not more sparing of his men. He had another mode of extortion. He demanded “aid” on many occasions, such as the marriage of his eldest daughter, or when he made his eldest son a knight. The estate of inheritance, which looks so generous and equitable an arrangement, was a perpetual grievance; for the possessor could neither transmit his property by will nor transfer it by sale. The heir, however remote in blood, was the only legitimate successor.

The feudal obligation to the lord was, in many other ways, a fruitful source of tyranny, which lasted up to the time of the Stuarts. If the heir were a minor, the lord entered into possession of the estate without any accountability. If it descended to a female, the lord could compel her to marry according to his will, or could prevent her marrying. During a long period all these harassing obligations connected with property were upheld. The crown and the nobles were equally interested in their enforcement; and there can be little doubt that, though the great vassals sometimes suffered under these feudal obligations to the king, the inferior tenants had a much greater amount of oppression to endure at the hands of their immediate lords. But if the freemen were oppressed in the tenure of their property, we can scarcely expect that the landless man had not much more to suffer. If he committed an offence in the Saxon time, he paid a “mulct”; if in the Norman, he was subjected to an amerciament. His whole personal estate was at the mercy of the lord.

Having thus obtained a general notion of the system of society established in less than twenty years after the Conquest, we see that there was nothing wanting to complete the most entire subjection of the great body of the nation. What had been wanting was accomplished in the practical working out of the theory that the entire land of the country belonged to the King. It was now established that every tenant-in-chief should do homage to the king; that every superior tenant should do homage to his lord; that every villein should be the bondman of the free; and that every slave should, without any property however limited and insecure, be the absolute chattel of some master. The whole system was connected with military service. This was the feudal system. There was some resemblance to it in parts of the Saxon organization; but under that organization there was so much of freedom in the allodial or free tenure of land that a great deal of other freedom went with it. The casting-off of the chains of feudality was the labor of six centuries.

| <—Previous | Master List |

This ends our series of passages on Domesday Book Completed by Charles Knight from his book Popular History of England published in 1860. This blog features short and lengthy pieces on all aspects of our shared past. Here are selections from the great historians who may be forgotten (and whose work have fallen into public domain) as well as links to the most up-to-date developments in the field of history and of course, original material from yours truly, Jack Le Moine. – A little bit of everything historical is here.

More information on Domesday Book Completed here and here and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.