This series has five easy 5 minute installments. This first installment: The Classes of Feudal England.

Introduction

When William the Conqueror had been some years established in his English realm, he found himself confronted with a feudal baronage largely composed of men who had gone with him from Normandy, where many of them had reluctantly bowed to his command. They were jealous of the royal power and eager for military and judicial independence within their own manors. The Conqueror met this situation with the skill of political genius. He granted large estates to the nobles, but so widely scattered as to render union of the great land-owners and hereditary attachment of great areas of population to separate feudal lords impossible. He caused under-tenants to be bound to their lords by the same conditions of service which bound the lords to the crown, to which each sub-tenant swore direct fealty. William also strengthened his position as king by means of a new military organization and by his control of the judicial and administrative systems of the kingdom. By the abolition of the four great earldoms of the realm he struck a final blow at the ambition of the greater nobles for independent power. By this stroke he made the shire the largest unit of local government. By his control of the national revenues he secured a great financial power in his own hands.

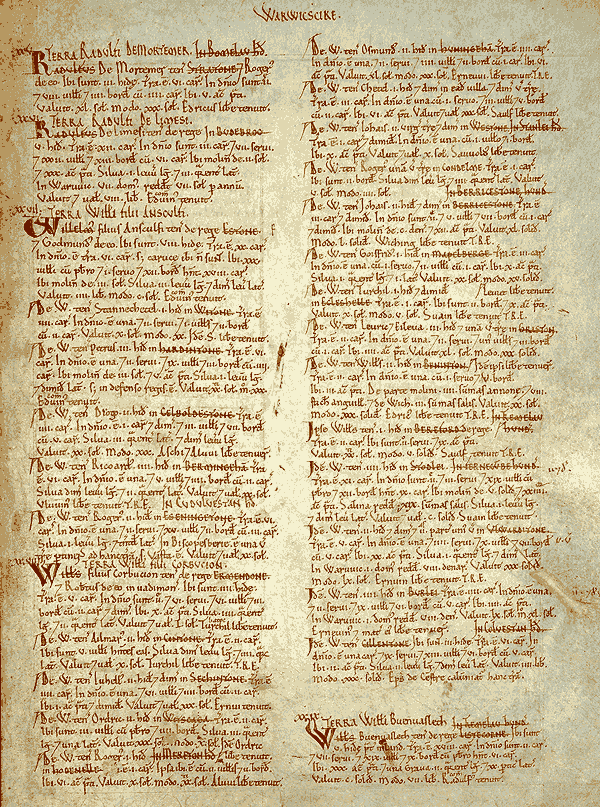

A large part of the manors were burdened with special dues to the crown, and for the purpose of ascertaining and recording these William sent into each county commissioners to make a survey, whose inquiries were recorded in the Domesday Book, so called because its decision was regarded as final. This book, in Norman-French, contains the results of his survey of England made in 1085-1086, and consists of two volumes in vellum, a large folio of three hundred and eighty-two pages, and a quarto of four hundred and fifty pages. For a long time it was kept under three locks in the exchequer with the King’s seal, and is now kept in the Public Record Office. In 1783 the British Government issued a facsimile edition of it, in two folio volumes, printed from types specially made for the purpose. It is one of the principal sources for the political and social history of the time.

The Domesday Book contains a record of the ownership, extent, and value of the lands of England at the time of the survey, at the time of their bestowal when granted by the King, and at the time of a previous survey under Edward the Confessor. Of the detailed registrations of tenants, defendants, livestock, etc., as well, as of contemporary social features of the English people, the following account presents interesting pictures.

This selection is from Popular History of England by Charles Knight published in 1860. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Charles Knight (1791-1873) was a publisher and a widely read author.

Time: 1086

Place: England

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

The survey contained in the Domesday Book extended to all England, with the exception of Northumberland, Cumberland, Westmoreland, and Durham. All the country between the Tees and the Tyne was held by the Bishop of Durham; and he was reputed a count palatine, having a separate government. The other three northern counties were probably so devastated that they were purposely omitted. Let us first see, from the information of Domesday Book, by “what men” the land was occupied.

First, we have barons and we have thanes. The barons were the Norman nobles; the thanes, the Saxon. These were included under the general designation of liberi homines, free men; which term included all the freeholders of a manor. Many of these were tenants of the King “in capite” — that is, they held their possessions direct from the Crown. Others of these had placed themselves under the protection of some lord, as the defender of their persons and estates, they paying some stipend or performing some service. In the Register there are also liberae feminae, free women. Next to the free class were the sochemanni or “socmen,” a class of inferior land-owners, who held lands under a lord, and owed suit and service in the lord’s court, but whose tenure was permanent. They sometimes performed services in husbandry; but those services, as well as their payments, were defined.

Descending in the scale, we come to the villani. These were allowed to occupy land at the will of the lord, upon the condition of performing services, uncertain in their amount and often of the meanest nature. But they could acquire no property in lands or goods; and they were subject to many exactions and oppressions. There are entries in Domesday Book which show that the villani were not altogether bondmen, but represented the Saxon “churl.” The lowest class were servi, slaves; the class corresponding with the Saxon theow. By a degradation in the condition of the villani, and the elevation of that of the servi, the two classes were brought gradually nearer together; till at last the military oppression of the Normans, thrusting down all degrees of tenants and servants into one common slavery, or at least into strict dependence, one name was adopted for both of them as a generic term, that of villeins regardant.

Of the subdivisions of these great classes, the Register of 1085 affords us some particulars. We find that some of the nobles are described as milites, soldiers; and sometimes the milites are classed with the inferior orders of tenantry. Many of the chief tenants are distinguished by their offices. We have among these the great regal officers, such as they existed in the Saxon times — the camerarius and cubicularius, from whom we have our lord chamberlain; the dapifer, or lord steward; the pincerna, or chief butler; the constable, and the treasurer. We have the hawkkeepers, and the bowkeepers; the providers of the king’s carriages, and his standard-bearers. We have lawmen, and legates, and mediciners. We have foresters and hunters.

Coming to the inferior officers and artificers, we have carpenters, smiths, goldsmiths, farriers, potters, ditchers, launders, armorers, fishermen, millers, bakers, salters, tailors, and barbers. We have mariners, moneyers, minstrels, and watchmen. Of rural occupations we have the beekeepers, ploughmen, shepherds, neatherds, goatherds, and swineherds. Here is a population in which there is a large division of labor. The freemen, tenants, villeins, slaves, are laboring and deriving sustenance from arable land, meadow, common pasture, wood, and water. The grain-growing land is, of course, carefully registered as to its extent and value, and so the meadow and pasture. An equal exactness is bestowed upon the woods. It was not that the timber was of great commercial value, in a country which possessed such insufficient means of transport; but that the acorns and beech-mast, upon which great herds of swine subsisted, were of essential importance to keep up the supply of food. We constantly find such entries as “a wood for pannage of fifty hogs.” There are woods described which will feed a hundred, two hundred, three hundred hogs; and on the Bishop of London’s demesne at Fulham a thousand hogs could fatten. The value of a tree was determined by the number of hogs that could lie under it, in the Saxon time; and in this survey of the Norman period, we find entries of useless woods, and woods without pannage, which to some extent were considered identical. In some of the woods there were patches of cultivated ground, as the entries show, where the tenant had cleared the dense undergrowth and had his corn land and his meadows. Even the fen lands were of value, for their rents were paid in eels.

There is only mention of five forests in this record, Windsor, Gravelings (Wiltshire), Winburn, Whichwood, and the New Forest. Undoubtedly there were many more, but being no objects of assessment they are passed over. It would be difficult not to associate the memory of the Conqueror with the New Forest, and not to believe that his unbridled will was here the cause of great misery and devastation. Ordericus Vitalis says, speaking of the death of William’s second son, Richard: “Learn now, my reader, why the forest in which the young prince was slain received the name of the New Forest. That part of the country was extremely populous from early times, and full of well-inhabited hamlets and farms. A numerous population cultivated Hampshire with unceasing industry, so that the southern part of the district plentifully supplied Winchester with the products of the land. When William I ascended the throne of Albion, being a great lover of forests, he laid waste more than sixty parishes, compelling the inhabitants to emigrate to other places, and substituted beasts of the chase for human beings, that he might satisfy his ardor for hunting.” There is probably some exaggeration in the statement of the country being “extremely populous from early times.” This was an old woody district, called Ytene. No forest was artificially planted, as Voltaire has imagined; but the chases were opened through the ancient thickets, and hamlets and solitary cottages were demolished.

| Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.