The Domesday Book affords us many curious glimpses of the condition of the people in cities and burghs.

Continuing Domesday Book Completed,

our selection from Popular History of England by Charles Knight published in 1860. The selection is presented in five easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Domesday Book Completed.

Time: 1086

Place: England

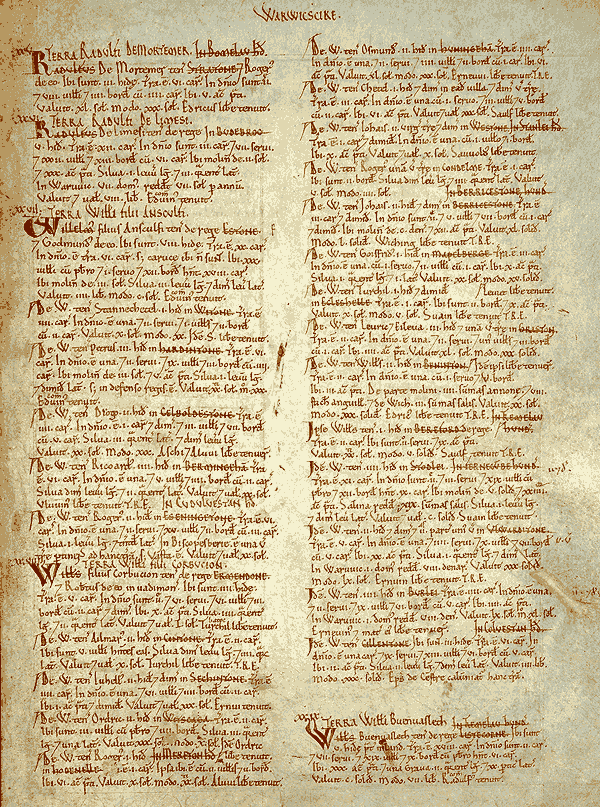

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

Fisheries are important sources of rent. Payments of eels are enumerated by hundreds and thousands. Herrings appear to have been consumed in vast numbers in the monasteries. Sandwich yielded forty thousand annually to Christ Church in Canterbury. Kent, Sussex, and Norfolk appear to have been the great seats of this fishery. The Severn and the Wye had their salmon fisheries, whose produce king, bishop, and lord were glad to receive as rent. There was a weir for Thames fish at Mortlake. The religious houses had their piscinae and vivaria — their stews and fish-pools.

Domesday affords us many curious glimpses of the condition of the people in cities and burghs. For the most part they seem to have preserved their ancient customs. London, Winchester, and several other important places are not mentioned in the record. We shall very briefly notice a few indications of the state of society. Dover was an important place, for it supplied the king with twenty ships for fifteen days in a year, each vessel having twenty-one men on board. Dover could therefore command the service of four hundred and twenty mariners. Every burgess in Lewes compounded for a payment of twenty shillings when the king fitted out a fleet to keep the sea.

At Oxford the king could command the services of twenty burgesses whenever he went on an expedition; or they might compound for their services by a payment of twenty pounds. Oxford was a considerable place at this period. It contained upward of seven hundred houses; but four hundred and seventy-eight were so desolated that they could pay no dues. Hereford was the king’s demesne; and the honor of being his immediate tenants appears to have been qualified by considerable exactions. When he went to war, and when he went to hunt, men were to be ready for his service. If the wife of a burgher brewed his ale, he paid tenpence. The smith who kept a forge had to make nails from the king’s iron. In Hereford, as in other cities, there were moneyers, or coiners. There were seven at Hereford, who were bound to coin as much of the king’s silver into pence as he demanded. At Cambridge the burgesses were compelled to lend the sheriff their ploughs. Leicester was bound to find the king a hawk or to pay ten pounds; while a sumpter or baggage-horse was compounded for at one pound.

At Warwick there were two hundred and twenty-five houses on which the king and his barons claimed tax; and nineteen houses belonged to free burgesses. The dues were paid in honey and corn. In Shrewsbury there were two hundred and fifty-two houses belonging to burgesses; but the burgesses complained that they were called upon to pay as much tax as in the time of the Confessor, although Earl Roger had taken possession of extensive lands for building his castle. Chester was a port in which the king had his dues upon every cargo, and where he had fines whenever a trader was detected in using a false measure. The fraudulent female brewer of adulterated beer was placed in the cucking-stool, a degradation afterward reserved for scolds.

This city has a more particular notice as to laws and customs in the time of the Confessor than any other place in the survey. Particular care seems to have been taken against fire. The owner of a house on fire not only paid a fine to the king, but forfeited two shillings to his nearest neighbor. Marten skins appear to have been a great article of trade in this city. No stranger could cart goods within a particular part of the city without being subjected to a forfeiture of four shillings or two oxen to the bishop. We find, as might be expected, no mention of that peculiar architecture of Chester called the “Rows,” which has so puzzled antiquarian writers. The probability is that in a place so exposed to the attacks of the Welsh they were intended for defence. The low streets in which the Rows are situated have the road considerably beneath them, like the cutting of a railway; and from the covered way of the Rows an enemy in the road beneath might be assailed with great advantage.

In the civil wars of Charles I the possession of the Rows by the Royalists, or Parliamentary troops, was fiercely contested. Of their antiquity there is no doubt. They probably belong to the same period as the Castle. The wall of Chester and the bridge were kept in repair, according to the survey, by the service of one laborer for every hide of land in the county. It is to be remarked that in all the cities and burghs the inhabitants are described as belonging to the king or a bishop or a baron. Many, even in the most privileged places, were attached to particular manors.

The Domesday survey shows that in some towns there was an admixture of Norman and English burgesses; and it is clear that they were so settled after the Conquest, for a distinction is made between the old customary dues of the place and those the foreigner should pay. The foreigner had to bear a small addition to the ancient charge. No doubt the Norman clung to many of the habits of his own land; and the Saxon unwillingly parted with those of the locality in which his fathers had lived. But their manners were gradually assimilated. The Normans grew fond of the English beer, and the English adopted the Norman dress.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.