“We command that all earls, barons, knights, sergeants . . . be always ready to perform to us their whole service, in manner as they owe it to us . . . .:

Continuing Domesday Book Completed,

our selection from Popular History of England by Charles Knight published in 1860. The selection is presented in five easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Domesday Book Completed.

Time: 1086

Place: England

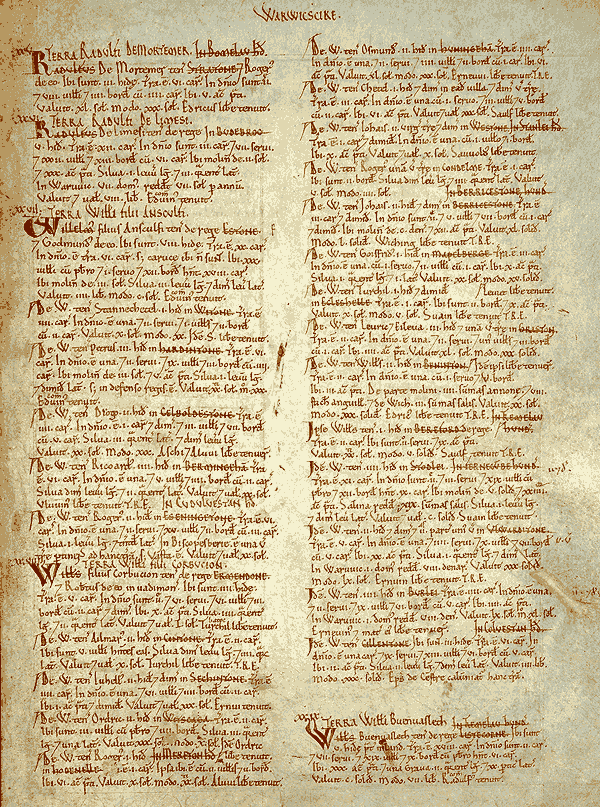

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

The survey of 1085 affords the most complete evidence of the extent to which the Normans had possessed themselves of the landed property of the country. The ancient demesnes of the crown consisted of fourteen hundred and twenty-two manors. But the king had confiscated the properties of Godwin, Harold, Algar, Edwin, Morcar, and other great Saxon earls; and his revenues thus became enormous. Ordericus Vitalis states, with a minuteness that seems to imply the possession of official information, that “the king himself received daily one-and-sixty pounds thirty thousand pence and three farthings sterling money from his regular revenues in England alone, independently of presents, fines for offences, and many other matters which constantly enrich a royal treasury.” The numbers of manors held by the favorites of the Conqueror would appear incredible, if we did not know that these great nobles were grasping and unscrupulous; indulging the grossest sensuality with a pretence of refinement; limited in their perpetration of injustice only by the extent of their power; and so blinded by their pride as to call their plunder their inheritance. Ten Norman chiefs who held under the crown are enumerated in the survey as possessing two thousand eight hundred and twenty manors.

This enormous transfer of property did not take place without the most formidable resistance, but when a period of tranquility arrived came the era of castle-building. The Saxons had their rude fortresses and entrenched earthworks. But solid walls of stone, for defense and residence, were to become the local seats of regal and baronial domination. Domesday contains notices of forty-nine castles; but only one is mentioned as having existed in the time of Edward the Confessor. Some which the Conqueror is known to have built are not noticed in the survey. Among these is the White Tower of London. The site of Rochester Castle is mentioned. These two buildings are associated by our old antiquaries as being erected by the same architect. Stow says: “I find in a fair register-book of the acts of the bishops of Rochester, set down by Edmund of Hadenham, that William I, surnamed Conqueror, builded the Tower of London, to wit, the great white and square tower there, about the year of Christ 1078, appointing Gundulph, then Bishop of Rochester, to be principal surveyor and overseer of that work, who was for that time lodged in the house of Edmere, a burghess of London.” The chapel in the White Tower is a remarkable specimen of early Norman architecture.

The keep of Rochester Castle, so picturesquely situated on the Medway, was not a mere fortress without domestic convenience. Here we still look upon the remains of sculptured columns and arches. We see where there were spacious fireplaces in the walls, and how each of four floors was served with water by a well. The third story contains the most ornamental portions of the building. In the Domesday enumeration of castles, we have repeated mention of houses destroyed and lands wasted, for their erection. At Cambridge twenty-seven houses are recorded to have been thus demolished. This was the fortress to overawe the fen districts. At Lincoln a hundred and sixty-six mansions were destroyed, “on account of the castle.”

In the ruins of all these castles we may trace their general plan. There were an outer court, an inner court, and a keep. Round the whole area was a wall, with parapets and loopholes. The entrance was defended by an outwork or barbacan. The prodigious strength of the keep is the most remarkable characteristic of these fortresses; and thus many of these towers remain, stripped of every interior fitting by time, but as untouched in their solid construction as the mounts upon which they stand. We ascend the steep steps which lead to the ruined keep of Carisbrook, with all our historical associations directed to the confinement of Charles I in this castle. But this fortress was registered in Domesday Book. Five centuries and a half had elapsed between William I and James I. The Norman keep was out of harmony with the principles of the seventeenth century, as much as the feudal prerogatives to which Charles unhappily clung.

We have thus enumerated some of the more prominent statistics of this ancient survey, which are truly as much matter of history as the events of this beginning of the Norman period. There is one more feature of this Domesday Book which we cannot pass over. The number of parish churches in England in the eleventh century will, in some degree, furnish an indication of the amount of religious instruction. By some most extraordinary exaggeration, the number of these churches has been stated to be above forty-five thousand. In Domesday the number enumerated is a little above seventeen hundred. No doubt this enumeration is extremely imperfect. Very nearly half of all the churches put down are found in Lincolnshire, Norfolk, and Suffolk. The Register, in some cases, gives the amount of land with which the church was endowed. Bosham, in Sussex, the estate of Harold, had, in the time of King Edward, a hundred and twelve hides of land. At the date of the survey it had sixty-five hides. This was an enormous endowment. Some churches had five acres only; some fifty; some a hundred. Some are without land altogether. But, whether the endowment be large or small, here is the evidence of a church planted upon the same foundation as the monarchy, that of territorial possessions.

The politic ruler of England had, in the completion of Domesday Book, possessed himself of the most perfect instrument for the profitable administration of his government. He was no longer working in the dark, whether he called out soldiers or levied taxes. He had carried through a great measure, rapidly, and with a minuteness which puts to shame some of our clumsy modern statistics. But the Conqueror did not want his books for the gratification of official curiosity. He went to work when he knew how many tenants-in-chief he could command, and how many men they could bring into the field. He instituted the great feudal principle of knight-service. His ordinance is in these words: “We command that all earls, barons, knights, sergeants, and freemen be always provided with horses and arms as they ought, and that they be always ready to perform to us their whole service, in manner as they owe it to us of right for their fees and tenements, and as we have appointed to them by the common council of our whole kingdom, and as we have granted to them in fee with right of inheritance.”

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.