“Go tell your master,” cried Mirabeau, “that we are here by order of the people; and that we shall not retire but at the point of the bayonet.”

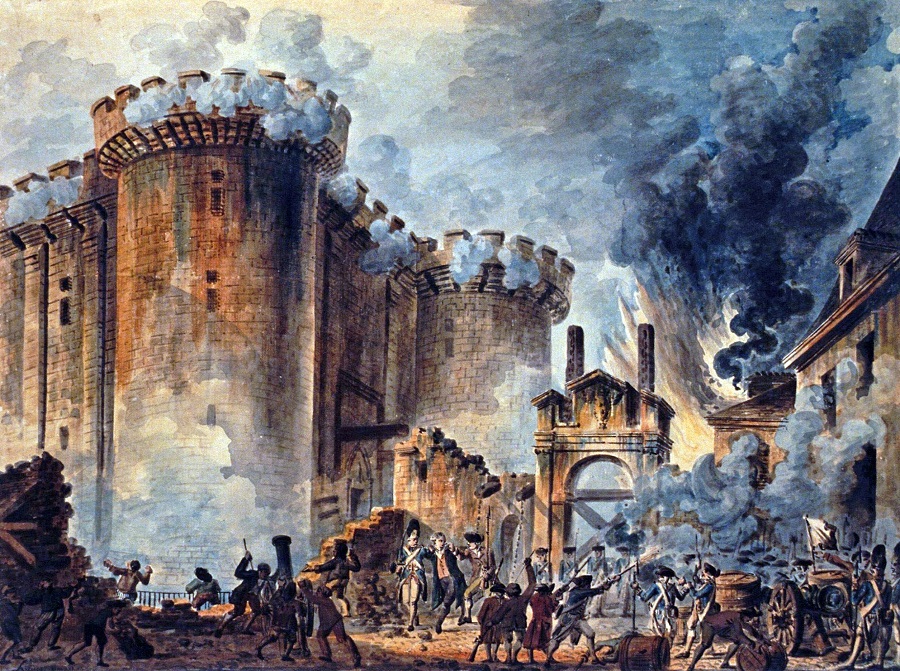

Continuing Revolutionaries Storm Bastille,

our selection from The Life of Napoleon Bounoparte by William Hazlitt published in 1830. The selection is presented in seven easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Revolutionaries Storm Bastille.

Time: July 14, 1789

Place: Paris

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

From this unbridled effusion of bombast, affectation, and real passion two things are evident: first, that the designs of the Court were already looked upon as altogether hostile and alien to the patriotic side; secondly, that the Assembly, from the beginning, felt in themselves the strong and undoubted conviction of their being called to the task of removing the abuses of power and regenerating the hopes of a mighty people. The die was cast, the lists were marked out in the opinions and sentiments of the two parties toward each other. The grand master of the ceremonies of this occasion, seeing that the Assembly did not break up, reminded them of the command of the King. “Go tell your master,” cried Mirabeau, “that we are here by order of the people; and that we shall not retire but at the point of the bayonet.” This was at once an invitation to violence and a defiance of authority. Sieyès added, with his customary coolness: “You are to-day in the same situation that you were yesterday; let us deliberate!” The Assembly immediately confirmed its former resolutions, and, at the instance of Mirabeau, decreed the inviolability of its members.

Such was at one time the brilliant, daring, and forward zeal of a man who not long after sold himself to the Court: so little has flashy eloquence or bold pretension to do with steadiness of principle! Indeed, the Revolution, of which he was one of the most prominent leaders, presented too many characters of this kind — dazzling, ardent, wavering, corrupt — a succession of momentary fires, made of light and worthless materials, soon kindled and soon exhausted, and requiring some new fuel to repair them: nothing deep, internal, relying on its own resources — “outliving fortunes outward with a mind that doth renew swifter than blood decays” — but a flame rash and violent, fanned by circumstances, kept alive by vanity, smothered by sordid interest, and wandering from object to object in search of the most contemptible and contradictory excitement! We may also remark, in the debates and proceedings of this early period, the fevered and anxious state of the public mind; while galling and intolerable abuses, called in question for the first time and defended with blind confidence, were exposed in the most naked and flagrant point of view; and the drapery of forms and circumstances was torn from rank and power with sarcastic petulance or a ruthless logic.

The resistance of the Assembly alarmed the Court, who did not, however, as yet dare to proceed against it. Necker, who had disapproved of the royal interference, and whose dismission had been determined on in the morning, was the same night entreated both by the King and Queen to stay. On the next meeting of the Assembly a large portion of the clergy again repaired to their place of sitting; and four days after, forty members of the noblesse joined them, with the Duke of Orléans at their head. The conduct of this nobleman, all through the Revolution, was in my opinion uncalled for, indecent, and profligate, and his fate not unmerited. Persons situated as he was cannot take a decided part one way or the other, without doing violence either to the dictates of reason and justice or to all their natural sentiments, unless they are characters of that heroic stamp as to be raised above suspicion or temptation: the only way for all others is to stand aloof from a struggle in which they have no alternative but to commit a parricide on their country or their friends, and to await the issue in silence and at a distance.

The people should not ask the aid of their lordly taskmasters to shake off their chains; nor can they ever expect to have it cordial and entire. No confidence can be placed in those excesses of public principle which are founded on the sacrifice of every private affection and of habitual self-esteem! The Court, soon after this reinforcement to the popular party, came forward of its own accord to request the attendance of the dissentient orders, which took place on June 27th; and after some petty ebullitions of jealousy and contests for precedence, the Assembly became general, and all distinctions were lost.

The King’s secret advisers were, however, by no means reconciled to this new triumph over ancient privilege and existing authority and meditated a reprisal by removing the Assembly farther from Paris, and there dissolving, if it could not overawe them. For this purpose the troops were collected from all parts; Versailles, where the Assembly sat, was like a camp; Paris looked as if it were in a state of siege. These extensive military preparations, the trains of artillery arriving every hour from the frontier, with the presence of the foreign regiments, occasioned great suspicion and alarm; and on the motion of Mirabeau, the Assembly sent an address to the King, respectfully urging him to remove the troops from the neighborhood of the capital; but this he declined doing, hinting at the same time that they might retire, if they chose, to Noyon or Soissons, thus placing themselves at the disposal of the Crown, and depriving themselves of the aid of the people.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.