Many forms of matter can evaporate, and many others emit scent; wherein, then, lies the peculiarity of radioactive substances, if the power of flinging away of atoms at tremendous speed is their central feature?

Continuing Early Science of Radioactivity,

Today we begin the second part of the series with our selection from Presidential Address to the British Association for the Advancement of Science by Sir William Ramsay published in either 1911 or 1912. The selection is presented in 3 easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Sir William Ramsay (1852-1916) received the Nobel Prize for “in recognition of his services in the discovery of the inert gaseous elements in air”. The Nobel Gasses opened a new section in the Periodic Table.

Previously in Early Science of Radioactivity.

Time: 1903

Place: Paris

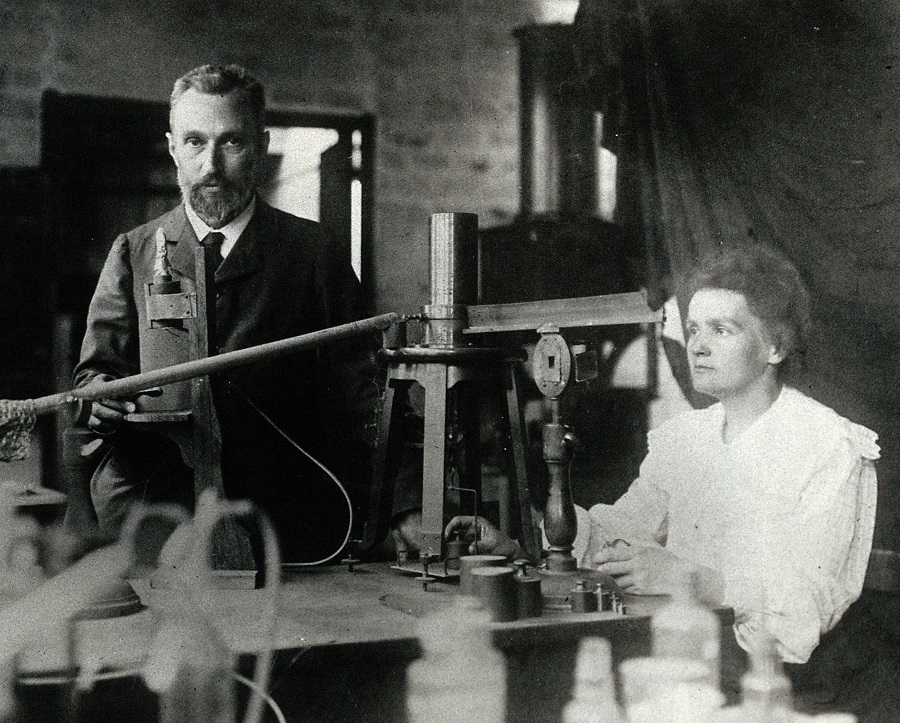

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

Radium, like other far less active substances previously discovered, is constantly emitting, without apparent diminution, three kinds of rays: rays called theta, which appear to be chiefly of the same nature as the x-rays of Rontgen; rays called alpha, or cathodic, which are found to consist of extremely minute flying corpuscles or electrons negatively charged; and rays called a, which appear to be composed of projected and positively charged atoms of matter flying away at an immense speed measured by Professor Rutherford, of Montreal. The whole power of emission is designated radioactivity, or spontaneous radioactivity to distinguish it from the variety which can be artificially excited in several ways, and was discovered in the first instance as a bare experimental fact by M. Becquerel. The most prominent, the most usually and easily demonstrated kind, are the beta rays; for these possess remarkable penetrating power and can excite phosphorescent substances or affect photographic plates and electroscopes after passing through a great length of air or even through an inch of solid iron. But although these are the most conspicuous, they are not the most important. The most important by far are the alpha rays, the flinging off of atoms of matter. It is probable that everything else is subordinate to this effect and can be regarded as a secondary and natural consequence of it.

For instance, undoubtedly radium or any salt of radium has the power of constantly generating heat: M. Curie has satisfactorily demonstrated this important fact. Not that it is to be supposed that a piece of radium is perceptibly warm, if exposed so that the heat can escape as fast as generated — it can then only be a trifle warmer than its surroundings; but when properly packed in a heat-insulating enclosure it can keep itself five degrees Fahrenheit above the temperature of any other substance enclosed in a similar manner; or when submerged in liquid air it can boil away that liquid faster than can a similar weight of anything else. Everything else, indeed, would rapidly get cooled down to the liquid-air temperature, and then cease to have any further effect; but radium, by reason of its heat-generating power, will go on evaporating the liquid continually, in spite of its surface having been reduced to the liquid-air temperature. But it is clear that this emission of heat is a necessary consequence of the vigorous atomic bombardment — at least, if it can be shown that the emission is due to some process occurring inside the atom itself, and not to any subsidiary or surrounding influences. Now that is just one of the features which are most conspicuous. Tested by any of the methods known, the radioactivity of radium appears to be constant and inalienable. Its power never deserts it. Whichever of its known chemical compounds be employed, the element itself in each is equally effective. At a red heat, or at the fearfully low temperature of liquid hydrogen, its activity continues; nothing that can be done to it destroys its radioactivity, nor even appears to diminish or increase it. It is a property of the atoms themselves, without regard, or without much regard, to their physical surroundings or to their chemical combination with the atoms of other substances. And this is one of the facts which elevate the whole phenomenon into a position of first- class importance.

The most striking test for radioactivity is the power of exciting phosphorescence in suitable substances: as, for instance, in diamond. Sir Wm. Crookes has shown that by bringing a scrap of radium, wrapped in any convenient opaque envelope, near a diamond in the dark, it glows brilliantly; whereas the “paste” variety remains dull. But although the excitation of phosphorescence is the most striking test and proof of the power of radioactivity, because it appeals so directly to the eye, it is by no means the most delicate test; and if that had been our only means of observation, the property would be still a long way from being discovered. It was the far weaker power of a few substances — substances found in Nature and not requiring special extraction and concentration, such as Madame Curie applied to tons of the oxide-of-uranium mineral called “pitchblende” in order to extract a minute amount of its concentrated active element — it was the far weaker power of naturally existing substances such as that of pitchblende itself, of thorium, and originally of uranium, which led to the discovery of radioactivity. And none of these substances is strong enough to excite visible phosphorescence. Their influence can be accumulated on a photo graphic plate for minutes, or hours, or days together, and then on developing the plate their radioactive record can be seen; but it is insufficient to appeal direct to the eye. In this photographic way the power of a number of minerals has been tested.

The emission of atoms does not seem, at first hearing, a very singular procedure on the part of matter. Many forms of matter can evaporate, and many others emit scent; wherein, then, lies the peculiarity of radioactive substances, if the power of flinging away of atoms at tremendous speed is their central feature? It all depends on what sort of atoms they are. If they are particles of the substance itself, there is nothing novel in it except the high speed ; but if it should turn out that the atoms flung off belong to quite a different substance — if one elementary body can be proved to throw off another elementary body — then clearly there is something worthy of stringent inquiry. Now, Rutherford has measured the atomic weight of the atoms thrown off, and has shown that they constitute less than i per cent. of the atoms whence they are projected; and that they probably consist of the metal helium.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Mme. Marie Curie begins here. Sir William Ramsay begins here. Sir Oliver Lodge begins here.

More information here and here, and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.