This series has seven easy 5 minute installments. This first installment: States-General Meets.

Introduction

In the scenes of blood and terror which accompanied it, and in the dramatic episodes and strange actors appearing upon its stage — in these respects, if not in the calculable effects of the uprising on France and the world, the French Revolution was the most extraordinary outbreak of modern times.

Matters in France at this time, or during the next few years, might have taken a very different course had not the Eastern powers of Europe been absorbed in their own quarrels, which culminated in the final “scramble for Polish territory.” As it was, France was left through the early years of the Revolution to struggle with her own affairs.

Under Louis XV, loved at the beginning of his reign, execrated by his people at its close, France had fallen into bankruptcy and disgrace. The monarchy was weakened through its head. Louis determined that it should live as long as he survived; he cared nothing for its future. The peasantry of France at this time had become keenly alive to the wrongs under which they had long suffered in comparative silence. The disfranchised bourgeois, or middle class, had lately grown in wealth and now thought more about their political rights. The “common” people were staggering under the burden of taxation, from which the privileged nobility and clergy were largely exempt.

The intellectual life of France during the second half of the eighteenth century was profoundly affected by the literature of the period, especially by the radical and revolutionary writings of Voltaire, Rousseau, and their followers, and in many things the extreme views of these men seemed to find confirmation in the calmer reasonings of Montesquieu on the powers and limitations of governments. Democratic ideas were in the air, and all except the privileged classes were ready for general revolt. Frenchmen returning from America reported the successful working of the new order of things inaugurated by the Revolution there, and this gave stronger impulse to the revolutionary tendency in France.

When the well-meaning but weak-willed Louis XVI came to the throne he found himself confronted with conditions before which a far abler monarch might well have quailed. How the storm broke upon him, and began its sweep over the kingdom which he was set to rule, is told by Hazlitt without the rhetorical flourishes indulged by many writers on this subject, but with clear narration and philosophic judgment of the facts recounted.

This selection is from The Life of Napoleon Bounoparte by William Hazlitt published in 1830. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

William Hazlitt (1778-1830) is now considered one of the greatest critics and essayists in the history of the English language.

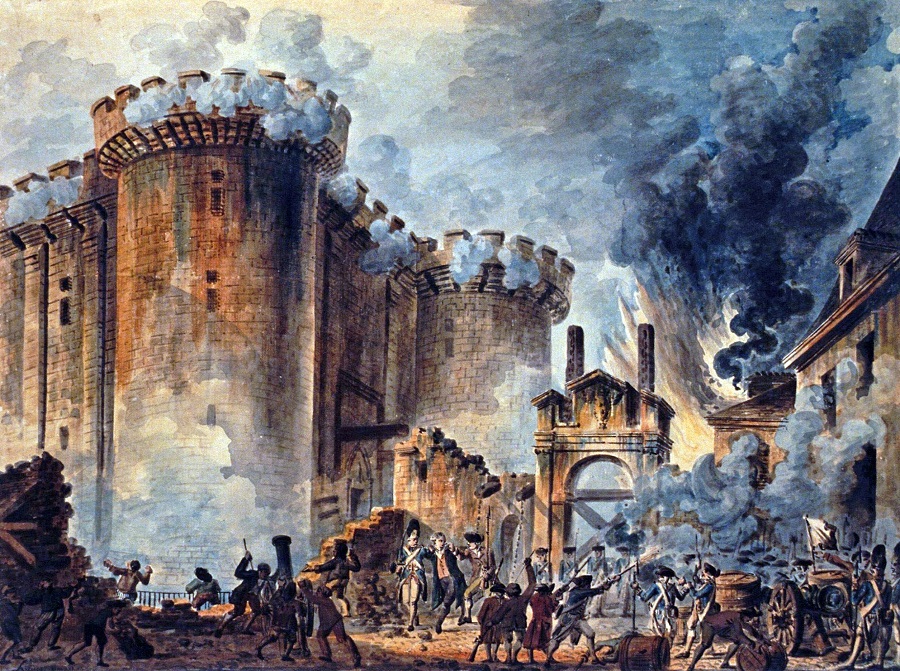

Time: July 14, 1789

Place: Paris

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

Louis XVI succeeded to the throne of France in 1774, and soon after married Marie Antoinette, a daughter of the house of Austria. She was young, beautiful, and thoughtless. In her the pride of birth was strengthened and rendered impatient of the least restraint by the pride of sex and beauty; and all three together were instrumental in hastening the downfall of the monarchy. Devoted to the licentious pleasures of a court, she looked both from education and habit on the homely comforts of the people with disgust or indifference, and regarded the distress and poverty which stood in the way of her dissipation with incredulity or loathing. * Louis XVI himself, though a man of good intentions, and free, in a remarkable degree, from the common vices of his situation, had not firmness of mind to resist the passions and importunity of others, and, in addition to the extravagance, petulance, and extreme counsels of the Queen, fell a victim to the intrigues and officious interference of those about him, who had neither the wisdom nor spirit to avert those dangers and calamities which they had provoked by their rashness, presumption, and obstinacy.

[* Edmund Burke passed a splendid and well-known eulogium on the beauty and accomplishments of the Queen, and it was in part the impression which her youthful charms had left in his mind that threw the casting-weight of his talents and eloquence into the scale of opposition to the French Revolution. I have heard another very competent judge, Mr. Northcote, describe her entering a small anteroom, where he stood, with her large hoop sideways, and gliding by him from one end to the other with a grace and lightness as if borne on a cloud. It was possibly to “this air with which she trod or rather disdained the earth,” as if descended from some higher sphere, that she owed the indignity of being conducted to a scaffold. Personal grace and beauty cannot save their possessors from the fury of the multitude, more than from the raging elements, though they may inspire that pride and self-opinion which expose them to it.]

The want of economy in the court, or a maladministration of the finances, first occasioned pecuniary difficulties to the Government, for which a remedy was in vain sought by a succession of ministers, Necker, Calonne, Maupeou, and by the Parliament. Considerable embarrassment and uneasiness began to be felt throughout the kingdom when in 1787 the King undertook to convoke the States-General, as alone competent to meet the emergency, and to confer on other topics of the highest consequence, which were at this time agitated with general anxiety and interest. The necessity of raising the supplies to defray the expenses of government was indeed only made the handle to introduce and enforce other more important and widely extended plans of reform.

For some time past the public mind had been growing critical and fastidious with the progress of civilization and letters; the monarchy, as it existed at the period “with all its imperfections on its head,” had been weighed in the balance of reason and opinion, and found wanting; and a favorable opportunity was only required, and the first that presented itself was eagerly seized to put in practice what had been already resolved upon in theory by the wits, philosophers, and philanthropists of the eighteenth century. From the first calling together the general council of the nation to deliberate and determine for the public good, in the then prevailing ferment of the popular feeling and with the predisposing causes, not a measure of finance was to be looked to, but a revolution became inevitable. All the cahiers, or instructions given to the deputies by the great mass of their constituents, show that the kingdom at large was ripe for a material change in its civil and political institutions, and for the most part point out the individual grievances which were afterward done away with.

The States-General met at Versailles on May 5, 1789. They consisted of the representatives of the nobility, of the clergy, and of the Tiers État or people in general, the number of the last having been doubled in order to equal that of the other two. They heard mass the evening before at the Church of St. Louis, in the same dresses, and with the same forms and order of precedence as in 1614, the last time they had ever been assembled. The King opened the sitting with a speech which gave little satisfaction, as it dwelt chiefly on the liquidation of the debt and the unsettled state of the public mind, and did not go into those general measures on which the views of the assembly were bent and from which alone relief was expected. The first question which divided opinion and led to a conflict was that regarding the vote by head or by order. By the first mode, that of counting voices, the commons would be numerically on a par with the privileged classes; by the latter, their opponents would always have the advantage of two to one. In order to keep this advantage, and prevent that reform of abuses which the Third Estate was supposed to have principally at heart, the Court did all it could to separate the different orders, first by adhering to etiquette, afterward by means of intrigue, and in the end by force.

| Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.