This first independent and spirited step on the part of the commons produced a reaction on the part of the Court.

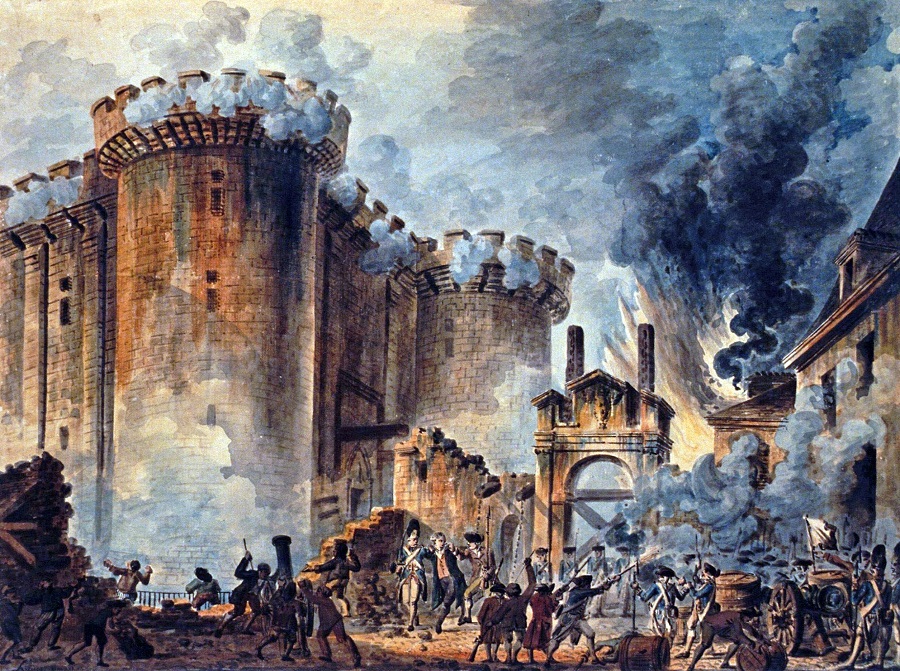

Continuing Revolutionaries Storm Bastille,

our selection from The Life of Napoleon Bounoparte by William Hazlitt published in 1830. The selection is presented in seven easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Revolutionaries Storm Bastille.

Time: July 14, 1789

Place: Paris

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

On the day following the meeting, the deputies of the three estates were called upon to verify their powers, which the nobles and clergy wished to do apart; but the commons refused to take any steps toward this object, except conjointly, or as a general legislative body. This led to various overtures and discussions, which lasted for several weeks. The Court offered its mediation; but the nobles giving a peremptory refusal to come to any compromise, at the motion of the Abbé Sieyès, the Third Estate, after in vain inviting the two others to join them, constituted themselves into a national assembly.

This was the first act of the Revolution, or the first occasion on which a part of a given body of individuals took upon them to decide for the rest, from the urgency and magnitude of the case, without the consent of their coadjutors, and contrary to established rules. It was a stroke of state necessity, to be defended not by the forms but by the essence of justice, and by the great ends of human society. The usurpation of a discretionary and illegal power was clear, but nothing could be done without it, everything with it. Yet so strong and natural is the prejudice against every appearance of what is violent and arbitrary, that serious attempts were made to reconcile the letter with the spirit of justice in this instance, and to prove that the Tiers État, being the representatives of the nation, and the nation being everything, the nobility and clergy were included in it and had nothing to complain of. It is not worth while to answer this sophistry. The truth is that the Third Estate erected themselves from parties concerned into framers of the law and judges of the reason of the case, and must themselves be judged, not by precedent and tradition, but by posterity, to whom, from the scale on which they acted, the benefit or the injury of their departure from common and worn-out forms will reach. Acts that supersede old established rules and create a new era in human affairs are to be approved or condemned by what comes after, not by what has gone before, them.

This first independent and spirited step on the part of the commons produced a reaction on the part of the Court. They shut up the place of sitting. The King had been prevailed on to consent to hostile measures against the popular side during an excursion to Marly with the Queen and princes of the blood. Bailly, afterward mayor of Paris, had been chosen president of the new National Assembly, and, arriving with other members, and finding the doors of the hall shut against them, they repaired to the Jeu de Paumes (“Tennis-court”) at Versailles, followed by the people and soldiers in crowds, and there, enclosed by bare walls, with heads uncovered, and a strong and spontaneous burst of enthusiasm, made a solemn vow, with the exception of only one person present, never to separate till they had given France a constitution.

This memorable and decisive event took place on June 20th. On the 23d the King came to the Church of St. Louis, whither they had been compelled to remove, and where they were joined by a considerable number of the clergy; addressed them in a tone of authority and reprimand, treated them as simply the Tiers État, pointed out certain partial reforms which he approved, and which he enjoined them to effect in conjunction with the other orders, or threatened to dissolve them and take the whole management of the government upon himself, and ended with a command that they should separate. The nobles and the clergy obeyed; the deputies of the people remained firm, immovable, silent.

Mirabeau then started from his seat and appealed to the Assembly in that mixed style of the academician and the demagogue which characterized his eloquence. The words are worth repeating here, both as a sample of the unqualified tone of the period and on account of the fierce and personal attack on the King, whom he stigmatizes by a sort of nickname. “Gentlemen, I acknowledge that what you have just heard might be a pledge of the welfare of the country, if the offers of despotism were not always dangerous. What is the meaning of this insolent dictation, the array of arms, the violation of the national temple, merely to command you to be happy? Who gives you this command? your Mandatory [‘deputy’]. Who imposes his imperious laws? your Mandatory, he who ought to receive them from you; from us, gentlemen, who are invested with an inviolable political priesthood; from us, in short, to whom, and to whom alone, twenty-five millions of men look up for a happiness insured by its being agreed upon, given, and received by all. But the freedom of your deliberations is suspended: a military force surrounds the Assembly! Where are the enemies of the nation, that this outrage should be attempted? Is Catiline at our gates? I demand that in asserting the claims of your insulted dignity, of your legislative power, you arm yourselves with the sanctity of your oath: it does not permit us to separate till we have achieved the constitution.”

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.