Atoms of matter are not simple, but complex; each is composed of an aggregate of smaller bodies in a state of rapid interlocked motion, restrained and coerced into orbits by electrical forces.

Continuing Early Science of Radioactivity,

with a selection from Presidential Address to the British Association for the Advancement of Science by Sir William Ramsay published in either 1911 or 1912. This selection is presented in 3 installments, each one 5 minutes long. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Early Science of Radioactivity.

Time: 1903

Place: Paris

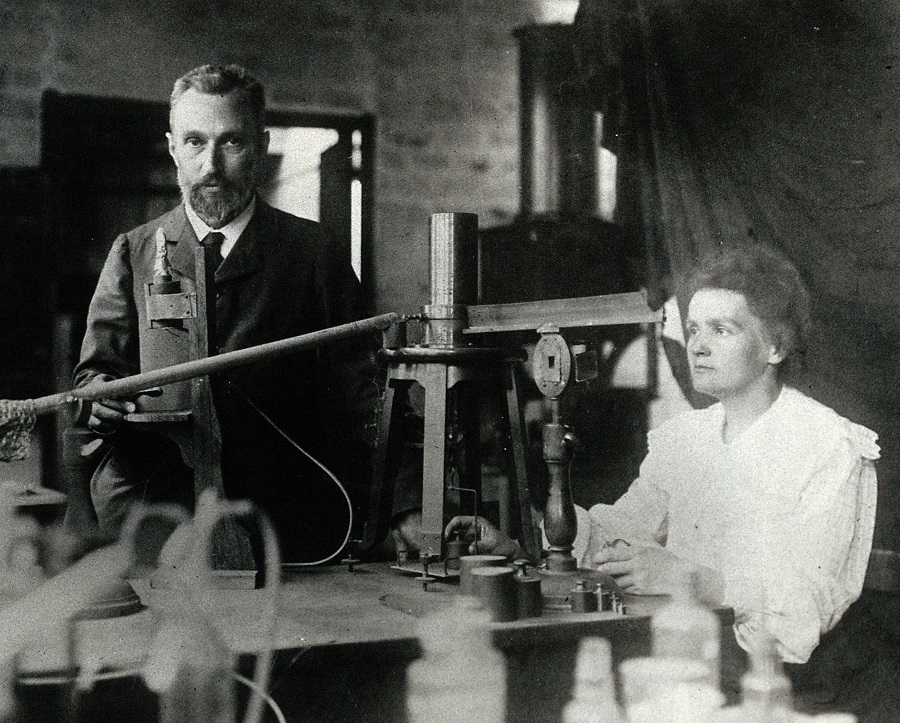

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

But the radioactivity of the substance itself — a substance like radium or thorium — is by no means the whole of what has to be described. When the emission has occurred, when the light atoms have been thrown off, it is clear that something must be left behind and the properties of that substance must be examined too. It appears to be a kind of heavy gas, which remains in the pores of the radium salt and slowly diffuses away. It can be drawn off more rapidly by a wind or current of air, and when passed over suitable phosphorescent substances it causes them to glow. It is, in fact, itself radioactive, as the radium was but its chemical nature is at present partly unknown. Its activity soon ceases, however, gradually fading away, so that in a few days or weeks it is practically gone. It leaves a radioactive deposit on surfaces over which it has passed; a deposit which is a different substance again, and whose chemical nature is likewise different and unknown. The amount of substance in these emanations and deposits is incredibly small, and yet by reason of their radioactivity, and the sensitiveness of our tests for that emission, they can be detected, and their properties to some extent examined. Thus, for instance, the solid deposit left behind by the radium emanation can be dissolved off by suitable reagents, and can then be precipitated or evaporated to dryness and treated in other chemical ways, although nothing is visible or weighable or detectable by any known means except the means of radioactivity. So that directly one of the chain of substances which emanate from a radioactive substance ceases to possess that particular kind of activity, it passes out of recognition; and what happens to it after that, or what further changes take place in it, remains at present absolutely unknown. So it is quite possible that these emanations and deposits and other products of spontaneous change may be emitted by many, perhaps all, kinds of matter, without our knowing anything whatever about it.

That being so, what is the meaning of the series of facts which have been here hastily summarized; and how are they to be accounted for? Here we come to the hypothetic and at present incompletely verified speculations and surmises, the possible truth of which is arousing the keenest interest. There are people who wish to warm their houses and cook their food and drive their engines and make some money by means of radium ; it is possible that these are doomed to disappointment, though it is always rash to predict anything whatever in the negative direction, and I would not be understood as making any prediction or indicating any kind of opinion, on the subject of possible practical applications of the substance, except, as we may hope, to medicine. Applications have their place, and in due time may come within the range of practicability, though there is no appearance of them at present. Meanwhile the real points of interest are none of these, but of a quite other order. The easiest way to make them plain is to state them as if they were certain, and not confuse the statement by constant reference to hypothesis: guarding myself from the beginning by what I have already said as to the speculative character of some of the assertions now going to be made.

Atoms of matter are not simple, but complex; each is composed of an aggregate of smaller bodies in a state of rapid interlocked motion, restrained and coerced into orbits by electrical forces. An atom so constituted is fairly stable and perennial, but not infinitely stable or eternal. Every now and then one atom in a million, or rather in a million millions, gets into an unstable state, and is then liable to break up. A very minute fraction of the whole number of the atoms of a substance do thus actually break up, probably by reason of an excessive velocity in some of their moving parts; an approach to the speed of light in some of their internal motions — perhaps the maximum speed which matter can ever attain — being presumably the cause of the instability. When the break-up occurs, the rapidly moving fragment flies away tangentially, with enormous speed — twenty thousand miles a second — and constitutes the alpha ray of main emission.

If the flying fragment strikes a phosphorescent obstacle, it makes a flash of light; if it strikes (as many must) other atoms of the substance itself, it gets stopped likewise, and its energy subsides into the familiar molecular motion we call “heat”; so the substance becomes slightly warmed. Energy has been transmuted from the unknown internal atomic kind to the known thermal kind: it has been degraded from regular orbital astronomical motion of parts of an atom into the irregular quivering of molecules; and the form of energy which we call heat has therefore been generated, making its appearance, as usual, by the disappearance of some other form, but, in this particular instance, of a form previously unrecognized.

Hitherto a classification of the various forms of energy has been complete when we enumerated rotation, translation, vibration, and strain, of matter in the form of planetary masses, ordinary masses, molecules, and atoms, and of the universal omnipresent medium “ether,” which is to “matter” as the ocean is to the shells and other conglomerates built out of its dissolved contents. But now we must add another category and take into consideration the parts or electrons of which the atoms of matter are themselves hypothetically composed.

The emission of the fragment is accompanied by a convulsion of the atom, minuter portions or electrons being pitched off too; and these, being so extraordinarily small, can proceed a long way through the interstices of ordinary obstacles, seeing, as it were, a clear passage every now and then even through an inch of solid lead, and constituting the beta rays; while the atoms themselves are easily stopped even by paper. But the recoil of the main residue is accompanied by a kind of shiver or rearrangement of the particles, with a suddenness which results in an x-ray emission such as always accompanies anything in the nature of a shock or collision among minute charged bodies; and this true ethereal radiation is the third or y ray of the whole process, and, like the heat- production, is a simple consequence of the main phenomenon, which is the break-up of the atom.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Mme. Marie Curie begins here. Sir William Ramsay begins here. Sir Oliver Lodge begins here.

More information here and here, and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.