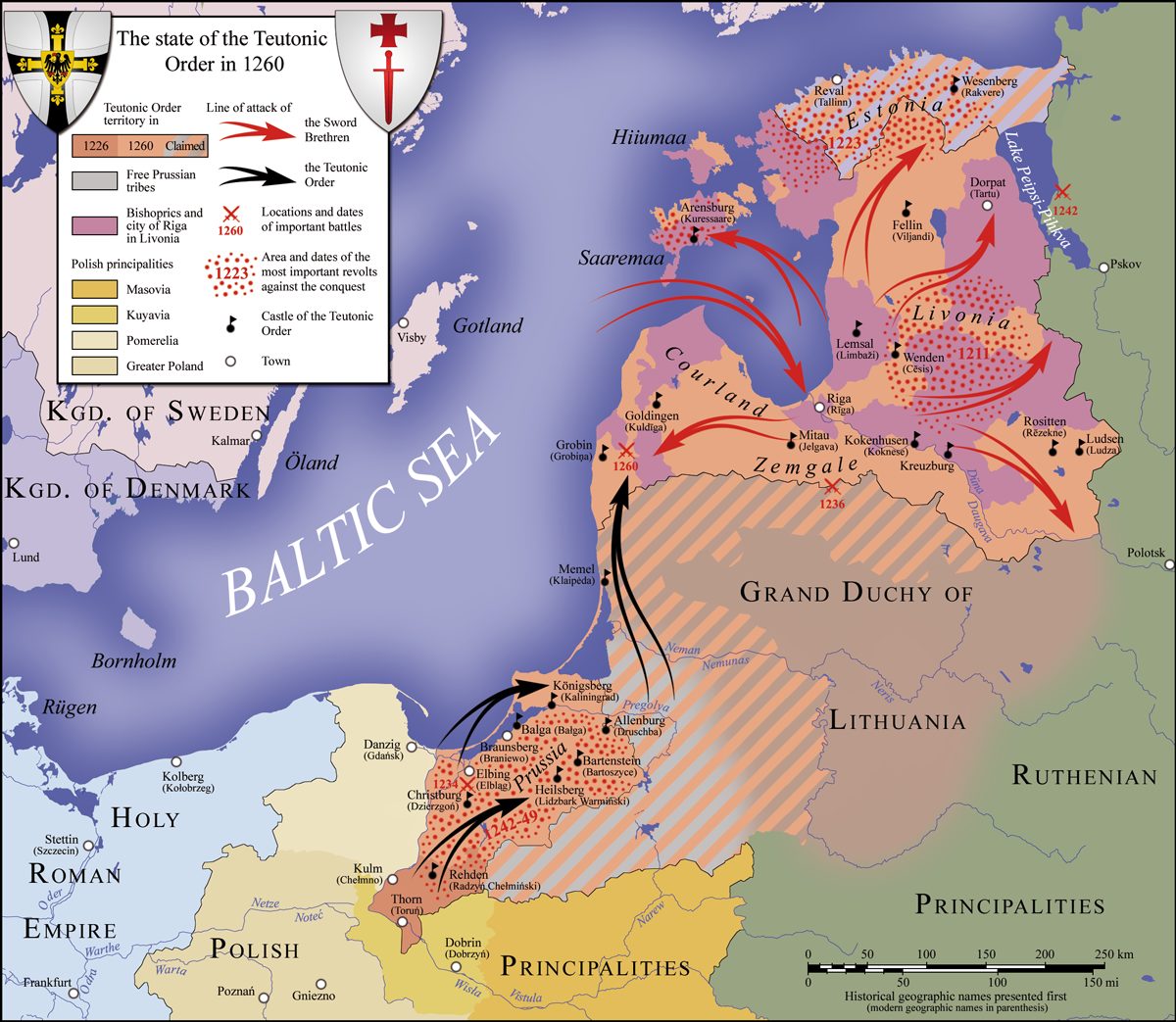

Besides large possessions in Germany, Italy, and other countries, its sovereignty extended from the Oder to the Gulf of Finland.

Continuing The Teutonic Knights,

our selection from The Military Religious Orders of the Middle Ages by Frederick C. Woodhouse published in 1879. The selection is presented in six easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in The Teutonic Knights.

Time: 1190-1809

Place: East Prussia

The times were indeed full of violence, cruelty, and crime. The annals abound with terrible and shameful records, bloody and desolating wars, and individual cases of oppression, injustice, and cruelty. Now a grand master is assassinated in his chapel during vespers; now a judge is proved to have received bribes, and to have induced a suitor to sacrifice the honor of his wife as the price of a favorable decision. Wealth and power led to luxury and sensuality, the weaker were oppressed, noble and bishop alike showing themselves proud and tyrannical. There are often two contradictory accounts of the same transaction, and it is impossible to decide where the fault really was, when there seems so little to choose between the conduct of either side.

The conclusion seems forced upon us that human nature was in those days much the same as it is now, and that riches and irresponsible authority scarcely ever fail to lead to pride and to selfish and oppressive treatment of inferiors. When we gaze upon the magnificent cathedrals that were rising all over Europe at the bidding of the great of those times, we are filled with admiration, and disposed to imagine that piety and a high standard of religious life must have prevailed; but a closer acquaintance with historical facts dissipates the illusion, and we find that then as now good and evil were mingled.

The history of the order for the next century presents little of interest. In 1388 two of the knights repaired to England by order of the grand master, to make commercial arrangements with that country, which had been rendered necessary by the changes introduced into the trade of Europe by the creation of the Hanseatic League. A second commercial treaty between the King of England and the order was made in 1409.

The order had now reached the summit of its greatness. Besides large possessions in Germany, Italy, and other countries, its sovereignty extended from the Oder to the Gulf of Finland. This country was both wealthy and populous. Prussia is said to have contained fifty-five large fortified cities, forty-eight fortresses, and nineteen thousand and eight towns and villages. The population of the larger cities must have been considerable, for we are told that in 1352 the plague carried off thirteen thousand persons in Dantzig, four thousand in Thorn, six thousand at Elbing, and eight thousand at Konigsberg. One authority reckons the population of Prussia at this time at two million one hundred and forty thousand eight hundred. The greater part of these were German immigrants, since the original inhabitants had either perished in the war or retired to Lithuania.

Historians who were either members of the order or favorably disposed toward it, are loud in their praise of the wisdom and generosity of its government; while others accuse its members and heads of pride, tyranny, luxury, and cruel exactions.

In 1410 the Teutonic order received a most crushing defeat at Tannenberg from the King of Poland, assisted by bodies of Russians, Lithuanians, and Tartars. The grand master, Ulric de Jungingen, was slain, with several hundred knights and many thousand soldiers. There is said to have been a chapel built at Gruenwald, in which an inscription declared that sixty thousand Poles and forty thousand of the army of the knights were left dead upon the field of battle. The banner of the order, its treasury, and a multitude of prisoners fell into the hands of the enemy, who shortly afterward marched against Marienberg and closely besieged it. Several of the feudatories of the knights sent in their submission to the King of Poland, who began at once to dismember the dominions of the order and to assign portions to his followers. But this proved to be premature. The knights found in Henry de Planau a valiant leader, who defended the city with such courage and obstinacy that, after fifty-seven days’ siege, the enemy retired, after serious loss from sorties and sickness. A series of battles followed, and finally a treaty of peace was signed, by which the order gave up some portion of its territory to Poland.

But a new enemy was on its way to inflict upon the order greater and more lasting injury than that which the sword could effect. The doctrines of Wycklif had for some time been spreading throughout Europe, and had lately received a new impulse from the vigorous efforts of John Huss in Bohemia, who had eagerly embraced them, and set himself to preach them, with additions of his own. Several knights accepted the teaching of Huss, and either retired from the order or were forcibly ejected. Differences and disputes also arose within the order, which ended in the arrest and deposition of the grand master in 1413. But the new doctrines had taken deep root, and a large party within the order were more or less favorable to them, so much so that at the Council of Constance (1415) a strong party demanded the total suppression of the Teutonic order. This was overruled; but it probably induced the grand master to commence a series of persecutions against those in his dominions who followed the principles of Huss.

The treaty that had followed the defeat at Tannenberg had been almost from the first disputed by both parties, and for some years appeals were made to the Pope and the Emperor on several points; but the decisions seldom gave satisfaction or commanded obedience. The general result was the loss to the order of some further portions of its dominions.

Another outbreak of the plague, in 1427, inflicted injury upon the order. In a few weeks no less than eighty-one thousand seven hundred and forty-six persons perished. There were also about this time certain visions of hermits and others, which threatened terrible judgments upon the order, because, while it professed to exist and fight for the honor of God, the defense of the Church, and the propagation of the faith, it really desired and labored only for its own aggrandizement.

It was said, too, that it should perish through a goose (oie), and as the word “Huss” means a goose in Bohemian patois, it was said afterward that the writings of Huss, or more truly, perhaps, the work of the goose-quill, had fulfilled the prophecy in undermining and finally subverting the order. There were also disputes respecting the taxes, which the people declared to be oppressive, and finally, in 1454, a formidable rebellion took place against the authority of the knights.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.