The measure of Catholic emancipation had recently been carried; and many of its opponents, of the Tory party, disgusted with their own leaders, by whom it had been forwarded, were suddenly converted to the cause of parliamentary reform.

Continuing English Reform Bill of 1832 Passes,

our selection from The Constitutional History of England snce the Accession of George III by Sir Thomas Erskine May published in 1863. The selection is presented in five easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in English Reform Bill of 1832 Passes.

Time: 1832

Place: London

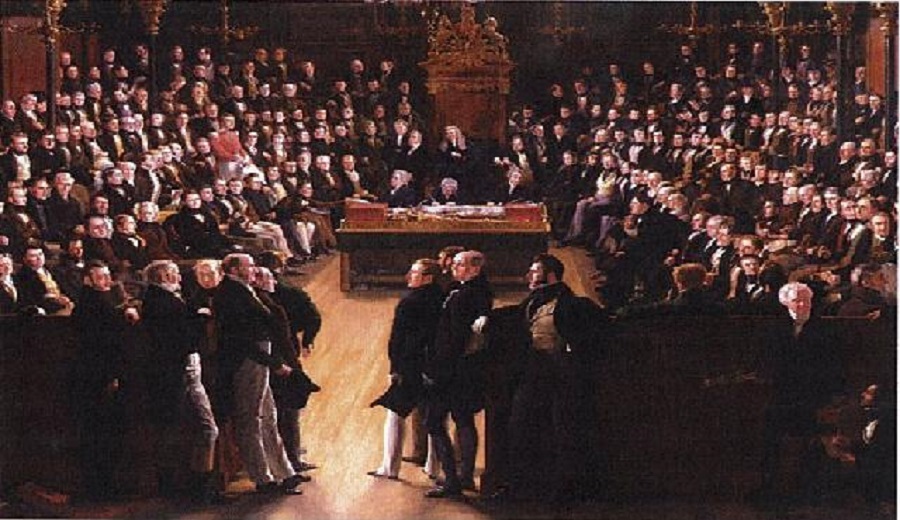

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

In 1823 Lord John renewed his motion in the same terms. He was now supported by numerous petitions, and among the number by one from seventeen thousand freeholders of the county of York, but, after a short debate, was defeated by a majority of one hundred eleven.

Again, in 1826, Lord John proposed the same resolution to the House, and pointed out forcibly that the increasing wealth and intelligence of the people were daily aggravating the inequality of the representation. Nomination boroughs continued to return a large proportion of the Members of the House of Commons, while places of enormous population and commercial prosperity were without representatives. After an interesting debate his resolution was negatived by a majority of one hundred twenty-four.

In 1829 a proposal for reform proceeded from an unexpected quarter and was based upon principles entirely novel. The measure of Catholic emancipation had recently been carried; and many of its opponents, of the Tory party, disgusted with their own leaders, by whom it had been forwarded, were suddenly converted to the cause of parliamentary reform. Representing their opinions, Lord Blandford on June 2nd submitted a motion on the subject. He apprehended that the Roman Catholics would now enter the borough-market and purchase seats for their representatives in such numbers as to endanger our Protestant Constitution. His resolutions condemning close and corrupt boroughs found only forty supporters and were rejected by a majority of seventy-four. At the beginning of the next session Lord Blandford repeated these views in moving an amendment to the address, representing the necessity of improving the representation. Being seconded by Mr. O’Connell, his anomalous position as a reformer was manifest.

Soon afterward he moved for leave to bring in a bill to restore the constitutional influence of the Commons in the Parliament of England, which contained an elaborate machinery of reform, including the restoration of wages to Members. His motion served no other purpose than that of reviving discussions upon the general question of reform.

But in the meantime questions of less general application had been discussed, which eventually produced the most important results. The disclosures that followed the general election of 1826, and the conduct of the Government, gave a considerable impulse to the cause of reform. The corporations of Northampton and Leicester were alleged to have applied large sums, from the corporate funds, for the support of ministerial candidates. In the Northampton case Sir Robert Peel went so far as to maintain the right of a corporation to apply its funds to election purposes; but the House could not be brought to concur in such a principle; and a committee of inquiry was appointed. In the Leicester case all inquiry was successfully resisted.

Next came two cases of gross and notorious bribery — Penryn and East Retford. They might have been easily disposed of; but, treated without judgment by the ministers, they precipitated a contest, which ended in the triumph of reform.

Penryn had long been notorious for its corruption, which had been already twice exposed; yet the ministers resolved to deal tenderly with it. Instead of disfranchising so corrupt a borough, they proposed to embrace the adjacent hundreds in the privilege of returning Members. But true to the principles he had already carried out in the case of Grampound, Lord John Russell succeeded in introducing an amendment in the bill by which the borough was to be entirely disfranchised.

In the case of East Retford a bill was brought in to disfranchise that borough and to enable the town of Birmingham to return two representatives; and it was intended by the reformers to transfer the franchise from Penryn to Manchester. The session closed without the accomplishment of either of these objects. The Penryn Disfranchisement Bill, having passed the Commons, had dropped in the Lords; and the East Retford bill had not yet passed the Commons.

In the next session two bills were introduced : one by Lord John Russell, for transferring the franchise from Penryn to Manchester; and another by Mr. Tennyson, for disfranchising East Retford and giving representatives to Birmingham. The Government proposed a compromise. If both boroughs were disfranchised, they offered, in one case to give two Members to a populous town, and in the other to the adjoining hundreds. When the Penryn bill had already reached the House of Lords, where its reception was extremely doubtful, the East Retford bill came on for discussion in the Commons. The Government now opposed the transference of the franchise to Birmingham. Mr. Huskisson, however, voted for it ; and his proffered resignation being accepted by the Duke of Wellington, led to the withdrawal of Lord Palmerston, Lord Dudley, Mr. Lamb, and Mr. Grant, the most liberal Members of the Government, the friends and colleagues of the late Mr. Canning. The Cabinet was now entirely Tory, and less disposed than ever to make concession to the reformers. The Penryn bill was soon afterward thrown out by the Lords on the second reading; and the East Retford bill, having been amended so as to retain the franchise in the hundreds, was abandoned in the Commons.

It was the opinion of many attentive observers of these times that the concession of demands so reasonable would have arrested, or postponed for many years, the progress of reform. They were resisted; and further agitation was encouraged.

In 1830 Lord John Russell, no longer hoping to deal with Penryn and East Retford, proposed at once to enfranchise Leeds, Birmingham, and Manchester, and to provide that the three next places proved guilty of corruption should be altogether disfranchised. His motion was opposed, mainly on the ground that if the franchise were given to these towns, the claims of other large towns could not afterward be resisted. Where, then, was such concession to stop? It is remarkable that on this occasion Mr. Huskisson said of Lord Sandon, who had moved an amendment, that he “was young, and would yet live to see the day when the representative franchise must be granted to the great manufacturing districts. He thought such a time fast approaching; and that one day or other His Majesty’s ministers would come down to that House to propose such a measure as necessary for the salvation of the country.” Within a year this prediction had been verified; though the unfortunate statesman did not live to see its fulfilment. The motion was negatived by a majority of forty-eight; and thus another moderate proposal, free from the objections which had been urged against disfranchisement, and not affecting any existing rights, was sacrificed to a narrow and obstinate dread of innovation.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.