A triumphant body of reformers was returned, pledged to carry the Reform Bill.

Continuing English Reform Bill of 1832 Passes,

our selection from The Constitutional History of England snce the Accession of George III by Sir Thomas Erskine May published in 1863. The selection is presented in five easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in English Reform Bill of 1832 Passes.

Time: 1831

Place: London

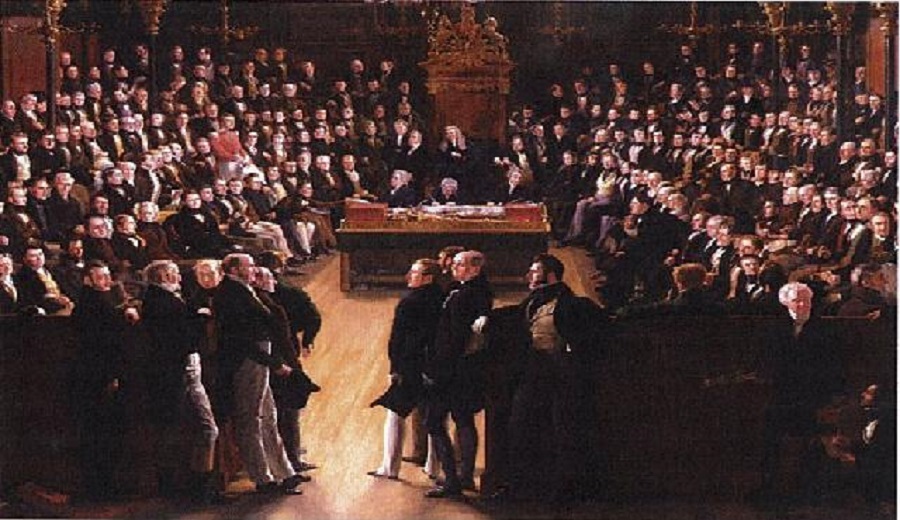

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

The Government were now pledged to a measure of parliamentary reform, and during the Christmas recess were occupied in preparing it. Meanwhile the cause was eagerly supported by the people. Public meetings were held, political unions established, and numerous petitions signed in favor of reform. So great were the difficulties with which the Government had to contend that they needed all the encouragement that the people could give. They had to encounter the reluctance of the King; the interests of the proprietors of boroughs, which Mr. Pitt, un able to overcome, had sought to purchase; the opposition of two- thirds of the House of Lords and perhaps of a majority of the House of Commons, and, above all, the strong Tory spirit of the country. Tory principles had been strengthened by a rule of sixty years. Not confined to the governing classes, but pervading society, they were now confirmed by the fears of impending danger. On the other hand, the too ardent reformers, while they alarmed the opponents of reform, embarrassed the Government and injured the cause by their extravagance.

On February 3rd, when Parliament reassembled, Lord Grey announced that the Government had succeeded in framing “a measure which would be effective, without exceeding the bounds of a just and well-advised moderation,” and which “had received the unanimous consent of the whole Government. ”

On March 1st this measure was brought forward in the House of Commons by Lord John Russell, to whom, though not in the Cabinet, this honorable duty had been justly confided. In the House of Commons he had already made the question his own; and now he was the exponent of the policy of the Government. The measure was briefly this: To disfranchise sixty of the smallest boroughs; to withdraw one Member from forty-seven other boroughs; to add eight Members for the metropolis; thirty- four for large towns; fifty-five for counties in England; and to give five additional Members to Scotland, three to Ireland, and one to Wales. By his new distribution of the franchise the House of Commons would be reduced in number from six hundred fifty-eight to five hundred ninety-six, or by sixty-two Members.

For the old rights of election in boroughs a ten-pound household franchise was substituted; and the corporations were deprived of their exclusive privileges. It was computed that half a million of persons would be enfranchised. Improved arrangements were also proposed for the registration of votes and the mode of polling at elections.

This bold measure alarmed the opponents of reform, and failed to satisfy the radical reformers; but on the whole, it was well received by the reform party and by the country. One of the most stirring periods in our history was approaching: but its events must be rapidly passed over. After a debate of seven nights, the bill was brought in without a division. Its opponents were collecting their forces, while the excitement of the people in favor of the measure was continually increasing. On March 22nd the second reading of the bill was carried by a majority of one only, in a House of six hundred eight, probably the greatest number which up to that time had ever been assembled at a division. On April 19th, on going into committee, ministers found themselves in a minority of eight on a resolution proposed by General Gascoyne, that the number of Members returned for England ought not to be diminished. On the 21st, ministers announced that it was not their intention to proceed with the bill. On that same night they were again defeated on a question of adjournment, by a majority of twenty-two.

This last vote was decisive. The very next day Parliament was prorogued by the King in person, “with a view to its immediate dissolution.” It was one of the most critical days in the history of our country. At a time of grave political agitation, the people were directly appealed to by the King’s Government to support a measure by which their feelings and passions had been aroused, and which was known to be obnoxious to both Houses of Parliament and to the governing classes.

The people were now to decide the question; and they decided it. A triumphant body of reformers was returned, pledged to carry the Reform Bill; and on July 6th the second reading of the renewed measure was agreed to, by a majority of one hundred thirty-six. The most tedious and irritating discussions ensued in committee, night after night; and the bill was not dis posed of until September 21st, when it was passed by a majority of one hundred nine.

That the Peers were still adverse to the bill was certain; but whether, at such a crisis, they would venture to oppose the national will was doubtful. On October 7th, after a debate of five nights, one of the most memorable by which that House has ever been distinguished, and itself a great event in history, the bill was rejected on the second reading by a majority of forty-one.

The battle was to be fought again. Ministers were too far pledged to the people to think of resigning; and on the motion of Lord Ebrington they were immediately supported by a vote of confidence from the House of Commons.

On October 20th Parliament was prorogued; and, after a short interval of excitement, turbulence, and danger, it met again on December 6th. A third reform bill was immediately brought in, changed in many respects, and much improved by reason of the recent census and other statistical investigations. Among other changes the total number of Members was no longer proposed to be reduced. The bill was read a second time on Sunday morning, December 18th, by a majority of one hundred sixty-two. On March 23rd it was passed by the House of Commons, and once more was before the House of Lords.

Here the peril of again rejecting it could not be concealed; the courage of some was shaken, the patriotism of others aroused; and after a debate of four nights the second reading was affirmed by the narrow majority of nine. But danger still awaited it. The Peers who would no longer venture to reject such a bill, were preparing to change its essential character by amendments. Meanwhile the agitation of the people was becoming dangerous. Compulsion and physical force were spoken of; and political unions and monster meetings assumed an attitude of intimidation. A crisis was approaching, fatal, perhaps, to the peace of the country; violence, if not revolution, seemed impending.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.