His statement raised a storm, which swept away his government and destroyed his party.

Continuing English Reform Bill of 1832 Passes,

our selection from The Constitutional History of England snce the Accession of George III by Sir Thomas Erskine May published in 1863. The selection is presented in five easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in English Reform Bill of 1832 Passes.

Time: 1832

Place: London

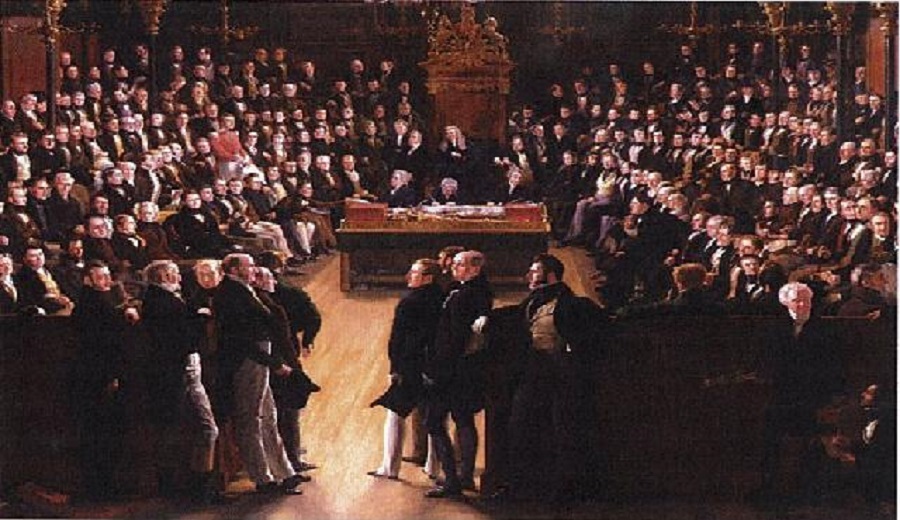

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

In this same session other proposals were made of a widely different character. Mr. O’Connell moved resolutions in favor of universal suffrage, triennial Parliaments, and vote by ballot. Lord John Russell moved to substitute other resolutions providing for the enfranchisement of large towns and giving additional Members to populous counties; while any increase of the numbers of the House of Commons was avoided by disfranchising some of the smaller boroughs, and restraining others from sending more than one Member. Sir Robert Peel, in the course of the debate, said: “They had to consider whether there was not, on the whole, a general representation of the people in that House, and whether the popular voice was not sufficiently heard. For himself he thought that it was.” This opinion was but the prelude to a more memorable declaration, by the Duke of Wellington. Both the motion and the amendment failed; but discussions so frequent served to awaken public sympathy in the cause, which great events were soon to arouse into enthusiasm.

At the end of this session Parliament was dissolved in consequence of the death of George IV. The Government was weak, parties had been completely disorganized by the passing of the Roman Catholic Relief Act; much discontent prevailed in the country; and the question of parliamentary reform, which had been so often discussed in the late session, became a popular topic at the elections. Meanwhile a startling event abroad added to the usual excitement of a general election. Scarcely had the writs been issued when Charles X of France, having attempted a coup-d’etat, lost his crown, and was an exile on his way to England. As he had fallen in violating the liberty of the press and subverting the representative Constitution of France, this sudden revolution gained the sympathy of the English people and gave an impulse to liberal opinions. The excitement was further increased by the revolution in Belgium, which immediately followed. The new Parliament, elected under such circumstances, met in October. Being without the restraint of a strong government, acknowledged leaders, and accustomed party connections, it was open to fresh political impressions; and the first night of the session determined their direction.

A few words from the Duke of Wellington raised a storm, which swept away his government and destroyed his party. In the debate on the address Earl Grey adverted to reform, and expressed a hope that it would not be deferred, like Catholic emancipation, until Government would be “compelled to yield to expediency what they refused to concede upon principle. This elicited from the Duke an ill-timed profession of faith in our representation.” He was fully convinced that the country possessed , at the present moment, a legislature which answered all the good purposes of legislation, and this to a greater degree than any legislature ever had answered, in any country whatever. He would go further, and say that the legislature and system of representation possessed the full and entire confidence of the country, deservedly possessed that confidence, and the discussions in the legislature had a very great influence over the opinions of the country. He would go still further, and say that if at the present moment he had imposed upon him the duty of forming a legislature for any country, and particularly for a country like this, in possession of great property of various descriptions, he did not mean to assert that he could form such a legislature as they possessed now, for the nature of man was incapable of reaching such excellence at once; but his great endeavor would be to form some description of legislature which would produce the same results. Under these circumstances he was not prepared to bring forward any measure of the description alluded to by the noble lord. He was not only not prepared to bring forward any measure of this nature, but he would at once declare that, as far as he was concerned, as long as he held any station in the government of the country, he should always feel it his duty to resist such measures when proposed by others.

At another time such sentiments as these might have passed unheeded, like other general panegyrics upon the British Constitution, with which the public taste had long been familiar. Yet, so general a defense of our representative system had never, perhaps, been hazarded by any statesman. Ministers had usually been cautious in advancing the theoretical merits of the system, even when its abuses had been less frequently exposed and public opinion less awakened. They had spoken of the dangers of innovation; they had asserted that the system, if imperfect in theory, had yet “worked well”; they had said that the people were satisfied and desired no change; they had appealed to revolutions abroad and disaffection at home, as reasons for not entertaining any proposal for change; but it was reserved for the Duke of Wellington, at a time of excitement like the present, to insult the understanding of the people by declaring that the system was perfect in itself and deservedly possessed their confidence.

On the same night Mr. Brougham gave notice of a motion on the subject of parliamentary reform. Within a fortnight the Duke’s administration resigned, after an adverse, division in the Commons, on the appointment of a committee to examine the accounts of the civil list. Though this defeat was the immediate cause of their resignation, the expected motion of Mr. Brougham was not without its influence in determining them to withdraw from further embarrassments.

Earl Grey was the new minister, and Mr. Brougham his Lord Chancellor. The first announcement of the Premier was that the Government would “take into immediate consideration the state of the representation, with a view to the correction of those defects which have been occasioned in it by the operation of time ; and with a view to the reestablishment of that confidence upon the part of the people which he was afraid Parliament did not at present enjoy to the full extent that is essential for the welfare and safety of the country and the preservation of the Government. ”

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.