This series has four easy 5 minute installments. This first installment: Metternich Establishes His Dominance.

Introduction

Before the allies had withdrawn from Paris after the fall of Napoleon in 1815, three Continental powers of Europe entered into a new alliance, from which England held aloof. It was formed by Alexander I of Russia, Francis I of Austria, and Frederick William III of Prussia, each of whom personally signed the agreement at Paris, September 26, 1815, when France also joined the alliance.

This event marked the beginning of a concerted reactionary policy on the part of the contracting powers, and led to the long ascendency of Prince Metternich, the Austrian minister, in European affairs. From this time he was leader of the repressive movement against popular aspirations for constitutional government and liberal institutions. The declared purpose of the alliance was to follow the teachings of the New Testament in political conduct. The sovereigns promised to rule ” strictly in accordance with the precepts of justice and Christian love and peace.” The relation of sovereign and subject was to be that of father and son. However sincerely founded, the alliance was soon perverted into an instrument of tyranny, sure to provoke fresh revolts, and after the French revolution of 1830 the league came to an end.

The part played by Metternich, the principal actor in those affairs with which the Holy Alliance concerned itself, is skillfully portrayed by Maurice, the historian of the later revolutionary period in Europe, who speaks with the highest authority of the reactionary influences against which, in due time, the progressive forces themselves reacted.

This selection is from Revolutionary Movements of 1848-1849 by Charles Edmund Maurice published in 1887. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Charles Edmund Maurice (1843-1927) was a writer with some insights on the history of this period.

Time: 1816

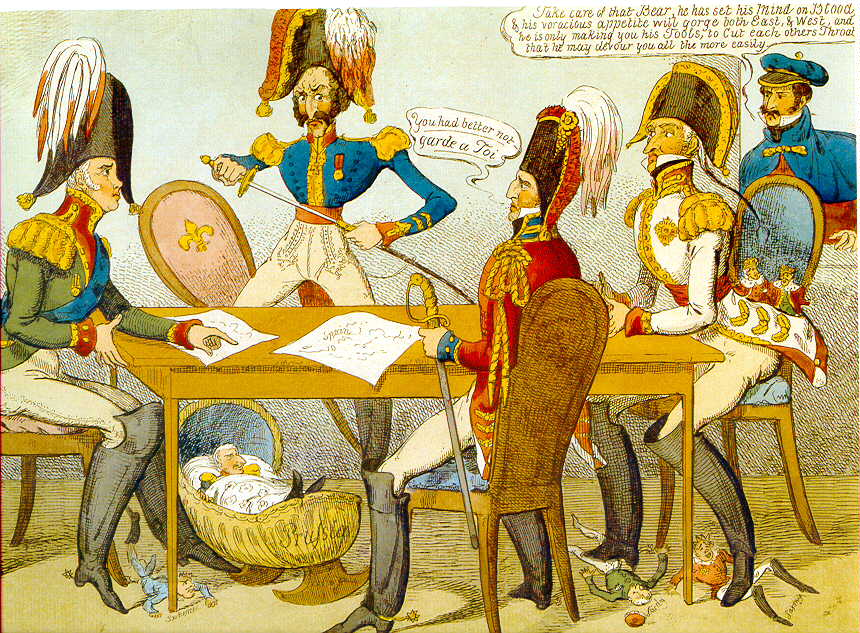

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

In the year 1814 Napoleon Bonaparte ceased to reign over Europe, and, after a very short interregnum, Clemens Metternich reigned in his stead. Ever since the fall of Stadion, and the collapse of Austria in 1809, this statesman had exercised the ‘ chief influence in Austrian affairs; and, by his skillful diplomacy, the Emperor had been enabled to play a part in Europe which, though neither honorable nor dignified, was eminently calculated to enable that prince to take a leading position in politics, when the other powers were exhausted by war, and uncertain of what was to follow. But Francis of Austria, though in agreement with Metternich, was really his hand rather than his head and thus, the crafty minister easily assumed the real headship of Europe, while professing to be the humble servant of the Emperor of Austria.

The King of Prussia, who in 1813 had seemed in danger of becoming the champion of popular rights and German freedom, was now, with his usual feebleness, swaying toward the side of despotism; and any irritation which he may have felt at the opposition to his claim upon Saxony had been removed by the con cession of the Rhine province.

Among the smaller sovereigns of Europe, the King of Sardinia and Pope Pius VII alone showed any signs of rebellion against the new ruler of Europe. The former had objected to the continued occupation of Alessandria by Austrian forces; while the representatives of the Pope had even entered a protest against that vague and dangerous clause in the Treaty of Vienna which gave Austria a right to occupy Ferrara.

But, on the other hand, the King of Sardinia had shown more zeal than any other ruler of Italy in restoring the old feudal and absolutist regime which the French had overthrown. And though Cardinal Consalvi, the chief adviser of the Pope, was following for the present a semi-liberal policy, he might as yet be considered as only having established a workable government in Rome. And the Pope, who had been kidnapped by Napoleon, was hardly likely to offer much opposition to the man who, in his own opinion, was the over-thrower of Napoleon.

Yet there were two difficulties which seemed likely to hinder the prosperity of Metternich’s reign. These were the character of Alexander I of Russia and the aspirations of the German nation.

Alexander, indeed, if occasionally irritating Metternich, evidently afforded him considerable amusement, and the sort of pleasure which every man finds in a suitable subject for the exercise of his peculiar talents. For Alexander was eminently a man to be managed. Enthusiastic, dreamy, and vain; now bent on schemes of conquest, now on the development of some ideal of liberty, now filled with some confused religious mysticism; at one time eager to divide the world with Napoleon, then anxious to restore Poland to its independence ; now listening to the appeals of Metternich to his fears, at another time to the nobler and more liberal suggestions of Stein and Pozzo di Borgo; he was only consistent in the one desire to play an impressive and melodramatic part in European affairs.

But, amusing as Alexander was to Metternich, there were circumstances connected with the condition of Europe which might make his weak love of display as dangerous to Metternich’s policy as a more determined opponent could be. There were still scattered over Europe traces of the old aspirations after liberty which had been first kindled by the French Revolution, and again awakened by the rising against Napoleon. Setting aside, for the moment, the leaders of German thought, there were men who had hoped that even Napoleon might give liberty to Poland; there were Spanish popular leaders who had arisen for the independence of their country; Lombards who had sat in the Assembly of the Cisalpine Republic; Carbonari in Naples, who had fought under Murat, and who had at one time received some little encouragement, even from their present king. If the Emperor of Russia should put himself at the head of such a com bination as this, the consequences to Europe might indeed be serious. But the stars in their courses fought for Metternich and a force that he had considered almost as dangerous as the character of Alexander proved the means of securing the Czar to the side of despotism.

Nothing is more characteristic of Metternich and his system than his attitude toward any kind of religious feeling. It might have been supposed that the anti-religious spirit which had shown itself in the fiercest period of the French Revolution, and to a large extent also in the career of Napoleon, would have induced the restorers of the old system to appeal both to clerical feeling and to religious sentiment as the most hopeful bulwark of legitimate despotism. Metternich was far wiser. He knew, in spite of the accidental circumstances which had connected atheism with the fiercer forms of Jacobinism, that, from the time of Moses to the time of George Washington, religious feeling had constantly been a tremendous force on the side of liberty; and although he might try to believe that to himself alone was due the fall of Napoleon, yet he could not but be aware that there were many who still fancied that the popular risings in Spain and Germany had contributed to that end, and that in both these cases the element of religious feeling had helped to strengthen the popular enthusiasm. He felt, too, that however much the clergy might at times have been made the tools of despotism, they did represent a spiritual force which might become dangerous to those who relied on the power of armies, the traditions of earthly kings, or the tricks of diplomatists. Much, therefore, as he may have disliked the levelling and liberating part of the policy of Joseph II, Metternich shared the hostility of that prince to the power of the clergy.

Nor was it purely from calculations of policy that Metternich was disposed to check religious enthusiasm. Like many of the nobles of his time he had come under the influence of the French philosophers of the eighteenth century; his hard and cynical spirit had easily caught the impress of their teaching; and he found it no difficult matter to flavor Voltairism with a slight tincture of respectable orthodox Toryism.

| Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.