Today’s installment concludes The Holy Alliance – European Reaction Under Metternich,

our selection from Revolutionary Movements of 1848-1849 by Charles Edmund Maurice published in 1887.

If you have journeyed through the installments of this series so far, just one more to go and you will have completed a selection from the great works of four thousand words. Congratulations! For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in The Holy Alliance – European Reaction Under Metternich.

Time: 1816

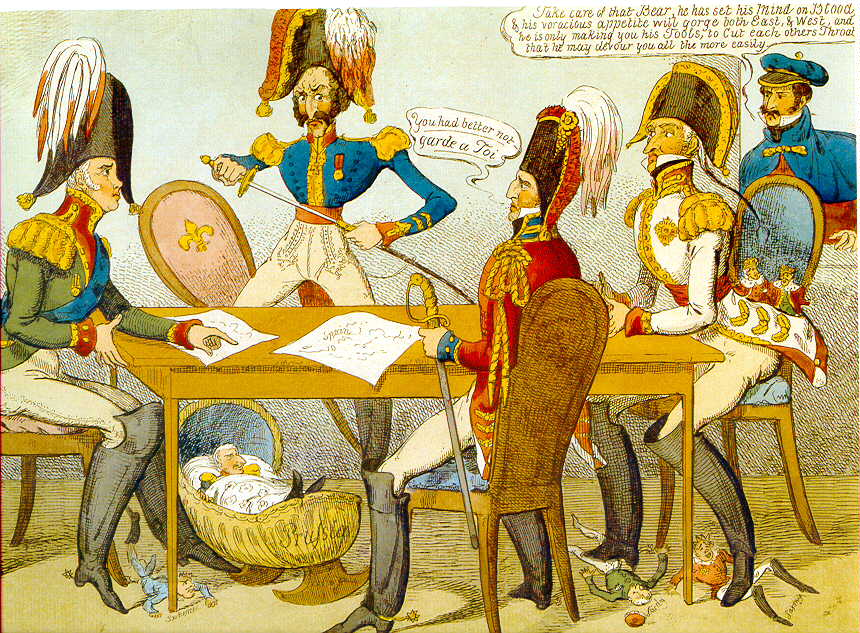

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

The head of the Rhine police, conscious, no doubt, of the ferment in his own province, remonstrated with the Duke of Weimar on permitting such disturbances. The opposition increased the movement which it was designed to check. Jahn, who had founded the gymnastic schools which had speedily become places of military exercise for patriotic Germans during the war, now came forward to organize a ” Burschenschafl,” a society that was to include all the patriotic students of Germany. Metternich and his friend had become thoroughly alarmed at the progress of the opposition, but again events seemed to work for him; and the enthusiasm of the students, ill-regulated and ill-guided, was soon to give an excuse for the blow that would secure the victory for a time to the champions of absolutism. The desire for liberty seems always to connect itself with love of symbolism; and the movement for reform naturally led to the revival of sympathy with earlier reformers. Actuated by these feelings, the students of Leipsic and other German universities gathered at the Wartburg, in 1817, to revive the memory of Luther’s testimony for liberty of thought; and they seized the opportunity for protesting against the tyranny of their own time.

Apparently the enthusiasm for the Emperor of Austria had not extended to Saxony; for an Austrian corporal’s staff was one of the first objects cast into the bonfire that was lighted by the students; while the dislike to Prussia was symbolized by the burning of a pair of Prussian military stays, and the hatred of the tyranny which prevailed in the smaller states found vent in the burning of a Hessian pigtail. The demonstration excited much disapproval among the stricter followers of Metternich; but Stein and others protested against any attempt to hinder the students in their meeting.

In the following year the Burschenschaft, which Jahn desired to form, began to take shape and to increase the alarm of the lovers of peace at all costs. Metternich rose to the occasion, and boasted that he had become a moral power in Europe, which would leave a void when it disappeared. In March, 1819, the event took place which at last gave this “moral power” a success that seemed for the moment likely to be lasting. Ludwig Sand, a young man who had studied first at Erlangen and afterward at Jena, went, on March 23, 1819, to the house of Kotzebue at Mannheim, and stabbed him to the heart. It was said, truly or falsely, that a paper was found with Sand, declaring that he acted with the authority of one of the universities. It was said also that Sand had played a prominent part in the Wartburg celebration. With the logic usual with panic-mongers, Metternich was easily able to deduce from these facts that the universities must, if left to themselves, become schools of sedition and murder.

The Duke of Weimar, with more courage, perhaps, than tact, had anticipated the designs of Metternich by a proclamation in favor of freedom of thought and teaching at the universities, as the best security for attaining truth. This proclamation strengthened still further the hands of Metternich. Abandoning the position which he had assumed at the Congress of Vienna, of champion of the smaller states of Germany, he appealed to the King of Prussia for help to coerce the Duke of Weimar and the German universities.

Frederick William, in spite of his support of Schmalz, was still troubled by some scruples of conscience. In May, 1815, he had made a public promise of a constitution to Prussia; Stein and Humboldt were eager that he should fulfil this promise, and even the less scrupulous Hardenberg held that it ought to be fulfilled sooner or later. But Metternich urged upon the King that he had allowed dangerous principles to grow in Prussia; that his kingdom was the center of conspiracy against the peace and order of Germany; and that, if he once conceded representative government, the other powers would be obliged to leave him to his fate. The King, already alarmed by the course which events were taking, was easily persuaded by Metternich to abandon a proposal that seemed to have nothing in its favor except the duty of keeping his word. Arndt was deprived of his professorship, and tried by commission on the charge of taking part in a republican conspiracy; Jahn was arrested, and Goerres fled from the country, to reappear in Bavaria as a champion of ultramontanism against the hateful influence of Prussia.

Then Mettemich proceeded to his master-stroke. He called a conference at Carlsbad to crush the revolutionary spirit of the universities. A commission of five members was appointed, under whose superintendence an official was to be placed over every university, to direct the minds and studies of students to sound political conclusions. Each government of Germany was to pledge itself to remove any teacher pronounced dangerous by this commission, and if any government resisted, the commission would compel it. No government was ever to accept a teacher so expelled from any other university. No newspaper of fewer than twenty pages was to appear without leave of a board, appointed for the purpose, and every state of Germany was to be answerable to the bund for the contents of its newspapers. The editor of a suppressed paper was to be, ipso facto, prohibited from establishing another paper for five years in any state of the bund; and a central board was to be founded for inquiry into demagogic plots.

These decrees seem a sufficiently crushing engine of despotism; but there still remained a slight obstacle to be removed from Metternich’s path. The Thirteenth Article of the Treaty of Vienna had suggested the granting of constitutions by different rulers of Germany; and, vaguely as it had been drawn, both Metternich and Francis felt this clause an obstacle in their path. As soon, therefore, as the Carlsbad Decrees had been passed, Metternich summoned anew the different states of Germany, to discuss the improvement of this clause. The representatives of Bavaria and Wurtemberg protested against this interference with the independence of the separate states; and, although the representative of Prussia steadily supported Metternich, it was necessary to make some concession in form to the opponents of his policy.

It was, therefore, decided that the princes of Germany should not be hindered in the exercise of their power, nor in their duty as members of the bund, by any constitutions. By this easy device Metternich was able to assume, without resistance, the imperial’ tone that suited his position. The entry in his Memoirs naturally marks this supreme moment of triumph. “I told my five-and-twenty friends,” he says, “what we want, and what we do not want; on this avowal there was a general declaration of approval, and each one asserted he had never wanted more or less, nor indeed anything different.”

Thus was Metternich recognized as the undisputed ruler of Germany, and, for the moment, of Europe.

| <—Previous | Master List |

This ends our series of passages on The Holy Alliance – European Reaction Under Metternich by Charles Edmund Maurice from his book Revolutionary Movements of 1848-1849 published in 1887. This blog features short and lengthy pieces on all aspects of our shared past. Here are selections from the great historians who may be forgotten (and whose work have fallen into public domain) as well as links to the most up-to-date developments in the field of history and of course, original material from yours truly, Jack Le Moine. – A little bit of everything historical is here.

More information on The Holy Alliance – European Reaction Under Metternich here and here and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.