His opposition to the unity of Germany, and his consequent attempt to pose as the champion of the separate states, had not tended to secure the despotic system which his soul loved.

Continuing The Holy Alliance – European Reaction Under Metternich,

our selection from Revolutionary Movements of 1848-1849 by Charles Edmund Maurice published in 1887. The selection is presented in four easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in The Holy Alliance – European Reaction Under Metternich.

Time: 1816

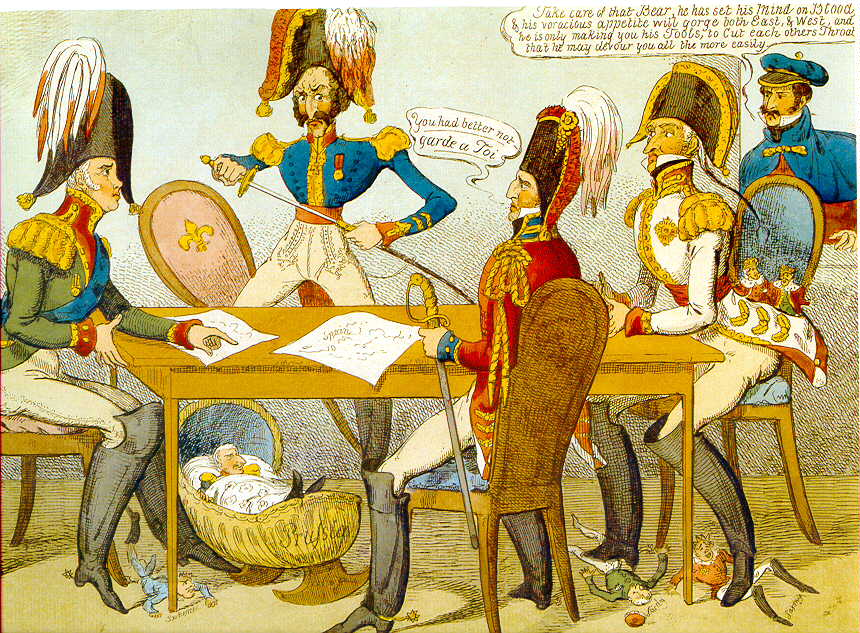

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

As he had been repelled from Metternich by arts like these, so Stein had been drawn to Arndt, Schleiermacher, and Steffens by a common love of honesty and by a common power of self-sacrifice but he looked upon them none the less as to a large extent dreamers and theorists and this want of sympathy with them grew, as the popular movement took a more independent form, until at last the champion of parliamentary government, the liberator of the Prussian peasant, the leader of the German people in the struggle against Napoleon, drifted entirely out of political life from want of sympathy with all parties.

But it was not to Stein alone that the Germans of 1813 had looked for help and encouragement in their struggle against Napoleon. The people had found other noble leaders at that period and it remembered them. The King of Prussia remembered them too, to his shame. He was perfectly aware that he had played a very sorry part in the beginning of the struggle, and that, instead of leading his people, he had been forced by them most unwillingly into the position of a champion of liberty. It was not, therefore, merely from a fear of the political effects of the constitutional movement, but from a more personal feeling, that Frederick William III was eager to forget the events of 1813.

But if the King wished to put aside uncomfortable facts, his flatterers were disposed to go much further, and to deny them. A man named Schmalz, who had been accused, rightly or wrongly, of having acted in 1808 with Scharnhorst in promoting the “Tugendbund,” and of writing in a democratic sense about popular assemblies, now wrote a pamphlet to vindicate himself against these charges. Starting from this personal standpoint, he went on to maintain that all which was useful in the movement of 1813 came directly from the King; that enterprises like that by which Schill endeavored to rouse the Prussians to a really popular struggle against the French were an entire mis take; that the political unions did nothing to stir up the people; that the alliance between Prussia and France in 1812 had saved Europe; and that it was not till the King gave the word in February, 1813, that the German people had shown any wish to throw off the yoke of Napoleon.

This pamphlet at once called forth a storm of indignation. Niebuhr and Schleiermacher both wrote answers to it, and the remaining popularity of the King received a heavy blow when it was found that he was checking the opposition, and had even singled out Schmalz for special honor. The great center of dis content was in the newly acquired Rhine province. The King of Prussia, indeed, had hoped that by founding a university at Bonn, by appointing Arndt professor of history, and Goerres, the former editor of the Rhenish Mercury (Rheinischer Merkur), director of public instruction, he might have secured the popular feeling in the province to his side.

But Arndt and Goerres were not men to be silenced by favor, any more than by fear. Goerres remonstrated with the King for giving a decoration to Schmalz, and organized petitions for enforcing the clause in the Treaty of Vienna which enabled the bund to summon the staende of the different provinces. Arndt renewed his demand for the abolition of serfdom in his own province of Ruegen, advocated peasant proprietorship, and, above all, parliamentary government for Germany. The feeling of discontent, which these pamphlets helped to keep alive, was further strengthened in the Rhine province by a growing feeling that Frederick William was trying to crush out local traditions and local independence by the help of Prussian officials.

So bitter was the anti-Prussian feeling produced by this conduct, that a temporary liking was excited for the Emperor of Austria, as an opponent of the Prussianizing of Germany; and Metternich, travelling in 1817 through this province, remarked that it is “no doubt the part of Europe where the Emperor is most loved, more even than in our own country.” But it was but a passing satisfaction that the ruler of Europe could derive from this accidental result of German discontent. He had already begun to perceive that his opposition to the unity of Germany, and his consequent attempt to pose as the champion of the separate states, had not tended to secure the despotic system which his soul loved.

Stein had opposed the admission of the smaller German states to the Vienna Congress, no doubt holding that unity of Germany would be better accomplished in this manner, and very likely distrusting Bavaria and Wurtemberg as former allies of Napoleon. Metternich, by the help of Talleyrand, had defeated this attempt at exclusion, and had secured the admission of Bavaria and Wurtemberg to the Congress. But he now found that these very states were thorns in his side.

They resented the attempts of Metternich to dictate to them in their internal affairs; and, though the King of Bavaria might confine himself to vague phrases about liberty, the King of Wurtemberg actually went the length of granting a constitution. Had the King lived much longer, Metternich might have been able to revive against him the remembrance of his former alliance with Napoleon. But when, after his death in 1816, the new King of Wurtemberg, a genuine German patriot, continued, in defiance of his nobles, to uphold his father’s constitution, this hope was taken away, and the South German states remained to the last, with more or less consistency, a hinderance to the completeness of Metternich’s system.

But the summary of Metternich’s difficulties in Germany is not yet complete. The ruler of another small principality, the Duke of Weimar, like the King of Wurtemberg, had taken advantage of the permission to grant a constitution to his people; and had been more prominent than even the King of Wurtemberg in encouraging freedom of discussion in his dominions. This love of freedom, in Weimar as in most countries of Europe, connected itself with university life, and thus found its center in the celebrated University of Jena; and on June 18, 1816, the students of the university met to celebrate the anniversary of the battle of Leipzig. There, to the great alarm of the authorities, they publicly burned the pamphlet of Schmalz, and another written by the playwriter Kotzebue, who was believed to have turned away Alexander of Russia from the cause of liberty, and now to be acting as his tool and spy.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.