Metternich had the wit to see that the piety of Alexander of Russia had now been turned into a direction which might be made use of for the enforcement of Metternich’s own system of government

Continuing The Holy Alliance – European Reaction Under Metternich,

our selection from Revolutionary Movements of 1848-1849 by Charles Edmund Maurice published in 1887. The selection is presented in four easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in The Holy Alliance – European Reaction Under Metternich.

Time: 1816

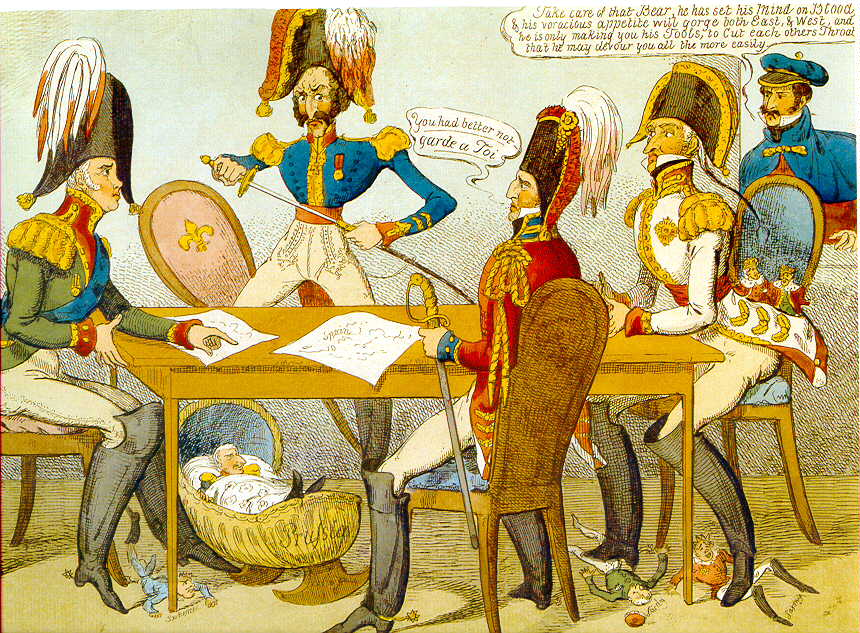

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

The method by which he achieved this end should be given in his own words:

I read every day one or two chapters of the Bible. I discover new beauties daily, and prostrate myself before this admirable book; while at the age of twenty I found it difficult not to think the family of Lot unworthy to be saved, Noah unworthy to have lived, Saul a great criminal, and David a terrible man. At twenty I tried to understand the Apocalypse; now I am sure that I never shall understand it. At the age of twenty a deep and long-continued search in the Holy Books made me an atheist after the fashion of Alembert and Lalande; or a Christian after that of Chateaubriand. Now I believe, and do not criticize. Accustomed to occupy myself with great moral questions, what have I not accomplished or allowed to be wrought out, before arriving at the point where the Pope and my cure’ begged me to accept from them the most portable edition of the Bible? Is it bold in me to take for certain that among a thousand individuals chosen from the men of whom the people are composed, there will be found, owing to their intellectual faculties, their education, or their age, very few who have arrived at the point where I find myself?”

This statement of his attitude of mind is taken from a letter written to remonstrate with the Russian ambassador on the patronage afforded by the Emperor Alexander to the Bible societies. But how much more would such an attitude of mind lead him to look with repugnance on the religious excitement that was displaying itself even in the archduchy of Austria! And to say the truth, men of far deeper religious feeling than Metternich might well be satisfied with the influence of the person who was the chief mover in this excitement.

The Baroness de Kruedener, formerly one of the gayest of Parisian ladies of fashion, and at least suspected of not having been too scrupulous in her conduct, had gone through the process which Carlyle so forcibly describes in his sketch of Ignatius Loyola. She had changed the excitements of religion, and was now preaching and prophesying a millennium of good things to come, in another world, to those who would abandon some of the more commonplace amusements of the present. The disturbance that she was producing in men’s minds especially alarmed Metternich; and, under what influence it may be difficult to prove, she was induced to retire to Russia, and there came in contact with the excitable Czar.

Under her influence Alexander drew up a manifesto, from which it appeared that, while all men were brothers, kings were the fathers of their peoples; Russia, Austria, and Prussia were different branches of one Christian people, who recognized no ruler save the Highest; and they were to combine to enforce Christian principles on the peoples of Europe. When the draft of this proclamation was first placed before Metternich it was so alien from his manner of thinking that he could only treat it with scorn; and Frederick William of Prussia was the only ruler who regarded it with even modified approval. But with all his scorn Metternich had the wit to see that the piety of Alexander of Russia had now been turned into a direction which might be made use of for the enforcement of Metternich’s own system of government; and thus, having induced Alexander, much against his will, to modify and alter the original draft, Metternich laid the foundation of the Holy Alliance.

But there still remained the troublesome question of the aspirations of the German nation; and these seemed likely at first to center in a man of far higher type and far more steady resolution than Alexander. This was Baron von Stein,* who, driven from office by Napoleon, had been in exile the point of attraction to all those who labored for the liberty of Germany. He had declared, at an early period, in favor of a German parliament. But Metternich had ingeniously succeeded in pitting against him the local feeling of the smaller German states; and instead of the real parliament which Stein desired, there arose that curious device for hindering national development called the “German Bund.”

[* This Prussian statesman had become the intimate counsellor of Alexander.— Ed.]

This was composed of thirty-nine members, representatives of all the different German governments. Its object was said to be to preserve the outward and inward safety of Germany, and the independence and inviolability of her separate states. If any change were to be made in fundamental laws, it could only be done by a unanimous vote. Some form of constitution was to be introduced in each state of the bund; arrangements were to be made with regard to the freedom of the press, and the bund was also to take into consideration the question of trade and intercourse between the different states. All the members of the bundestag were to protect Germany, and each individual state, against every attack. The vagueness and looseness of these provisions enabled Metternich so to manage the bundestag as to defeat the object of Stein and his friends, and gradually to use this weakly constituted assembly as an effective engine of despotism.

But in fact Stein was ill fitted to represent the popular feeling in any efficient manner. His position is not altogether easy to explain. He believed, to some extent, in the people, especially the German people. That is to say, he believed in the power of that people to feel justly and honorably; and, as long as that feeling was expressed in the form of a cry to their rulers to guide and lead justly, he was as anxious as anyone that that cry be heard. He liked, too, the sense of the compact embodiment of this feeling in some institution representing the unity of the nation. But with the ideas connected with popular representation in the English sense he had little sympathy. That the people or their representatives should reason or act, independently of their sovereigns, was a political conception which was abhorrent to him.

In short, Stein’s antagonism to Metternich was as intense as that of the most advanced democrat; but it was not so much the opposition of a champion of freedom to a champion of despot ism as the opposition of an honest man to a rogue. Metternich wrote in his Memoirs, when he was taking office for the first time in 1809: “From the day when peace is signed we must con fine our system to tacking and turning and flattering. Thus alone may we possibly preserve our existence till the day of general deliverance.” This policy had been consistently followed. The abandonment of Andrew Hofer after the Tyrolese rising of 1809, the marriage of Maria Louisa, the alliance with Napoleon, the discouragement of all popular effort to throw off the French yoke, the timely desertion of Napoleon’s cause, just soon enough to give importance to the alliance of Austria with Prussia and Russia and England, just late enough to prevent any danger of defeat and misfortune — these acts marked the character of Metternich’s policy and excited the loathing of Stein.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.