Difficulties grew to such an extent in 1917 that a dictatorship was set up and soon after came an interlude, the recall of the Manchus and the reinstatement of the deposed emperor (July 1st-8th, 1917).

Continuing The Republic of China,

our selection from A History of China by Wolfram Eberhard published in 1969. The selection is presented in nine easy 5-minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in The Republic of China.

Time: 1905-1948

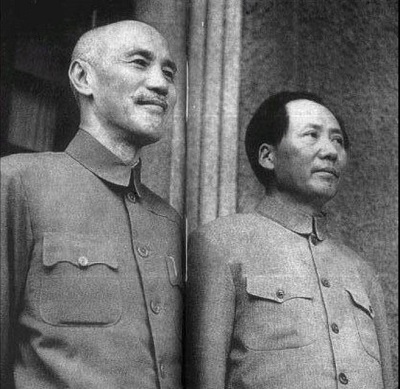

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

China’s internal difficulties reacted on the border states, in which the European powers were keenly interested. The powers considered that the time had come to begin the definitive partition of China. Thus, there were long negotiations and also hostilities between China and Tibet, which was supported by Great Britain. The British demanded the complete separation of Tibet from China, but the Chinese rejected this (1912); the rejection was supported by a boycott of British goods. In the end the Tibet question was left undecided. Tibet remained until recent years a Chinese dependency with a good deal of internal freedom. The Second World War and the Chinese retreat into the interior brought many Chinese settlers into Eastern Tibet which was then separated from Tibet proper and made a Chinese province (Hsi-k’ang) in which the native Khamba will soon be a minority. The communist régime soon after its establishment conquered Tibet (1950) and has tried to change the character of its society and its system of government which lead to the unsuccessful attempt of the Tibetans to throw off Chinese rule (1959) and the flight of the Dalai Lama to India. The construction of highways, air and missile bases and military occupation have thus tied Tibet closer to China than ever since early Manchu times.

In Outer Mongolia Russian interests predominated. In 1911 there were diplomatic incidents in connection with the Mongolian question. At the end of 1911 the Hutuktu of Urga declared himself independent, and the Chinese were expelled from the country. A secret treaty was concluded in 1912 with Russia, under which Russia recognized the independence of Outer Mongolia, but was accorded an important part as adviser and helper in the development of the country. In 1913 a Russo-Chinese treaty was concluded, under which the autonomy of Outer Mongolia was recognized, but Mongolia became a part of the Chinese realm. After the Russian revolution had begun, revolution was carried also into Mongolia. The country suffered all the horrors of the struggles between White Russians (General Ungern-Sternberg) and the Reds; there were also Chinese attempts at intervention, though without success, until in the end Mongolia became a Soviet Republic. As such she is closely associated with Soviet Russia. China, however, did not quickly recognize Mongolia’s independence, and in his work China’s Destiny (1944) Chiang Kai-shek insisted that China’s aim remained the recovery of the frontiers of 1840, which means among other things the recovery of Outer Mongolia. In spite of this, after the Second World War Chiang Kai-shek had to renounce de jure all rights in Outer Mongolia. Inner Mongolia was always united to China much more closely; only for a time during the war with Japan did the Japanese maintain there a puppet government. The disappearance of this government went almost unnoticed.

At the time when Russian penetration into Mongolia began, Japan had entered upon a similar course in Manchuria, which she regarded as her “sphere of influence”. On the outbreak of the first world war Japan occupied the former German-leased territory of Tsingtao, at the extremity of the province of Shantung, and from that point she occupied the railways of the province. Her plan was to make the whole province a protectorate; Shantung is rich in coal and especially in metals. Japan’s plans were revealed in the notorious “Twenty-one Demands” (1915). Against the furious opposition especially of the students of Peking, Yüan Shih-k’ai’s government accepted the greater part of these demands. In negotiations with Great Britain, in which Japan took advantage of the British commitments in Europe, Japan had to be conceded the predominant position in the Far East.

Meanwhile Yüan Shih-k’ai had made all preparations for turning the Republic once more into an empire, in which he would be emperor; the empire was to be based once more on the gentry group. In 1914 he secured an amendment of the Constitution under which the governing power was to be entirely in the hands of the president; at the end of 1914 he secured his appointment as president for life, and at the end of 1915 he induced the parliament to resolve that he should become emperor.

This naturally aroused the resentment of the republicans, but it also annoyed the generals belonging to the gentry, who had had the same ambition. Thus, there were disturbances, especially in the south, where Sun Yat-sen with his followers agitated for a democratic republic. The foreign powers recognized that a divided China would be much easier to penetrate and annex than a united China, and accordingly opposed Yüan Shih-k’ai. Before he could ascend the throne, he died suddenly — and this terminated the first attempt to re-establish monarchy.

Yüan was succeeded as president by Li Yüan-hung. Meanwhile five provinces had declared themselves independent. Foreign pressure on China steadily grew. She was forced to declare war on Germany, and though this made no practical difference to the war, it enabled the European powers to penetrate further into China. Difficulties grew to such an extent in 1917 that a dictatorship was set up and soon after came an interlude, the recall of the Manchus and the reinstatement of the deposed emperor (July 1st-8th, 1917).

This led to various risings of generals, each aiming simply at the satisfaction of his thirst for personal power. Ultimately the victorious group of generals, headed by Tuan Ch’i-jui, secured the election of Fêng Kuo-chang in place of the retiring president. Fêng was succeeded at the end of 1918 by Hsü Shih-ch’ang, who held office until 1922. Hsü, as a former ward of the emperor, was a typical representative of the gentry, and was opposed to all republican reforms.

The south held aloof from these northern governments. In Canton an opposition government was set up, formed mainly of followers of Sun Yat-sen; the Peking government was unable to remove the Canton government. But the Peking government and its president scarcely counted any longer even in the north. All that counted were the generals, the most prominent of whom were: (1) Chang Tso-lin, who had control of Manchuria and had made certain terms with Japan, but who was ultimately murdered by the Japanese (1928); (2) Wu P’ei-fu, who held North China; (3) the so-called “Christian general”, Fêng Yü-hsiang, and (4) Ts’ao K’un, who became president in 1923.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

|

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.