By far the most skillful player in this game, and at the same time the man who had the support of the foreign governments and of the financiers of Shanghai, he gained the victory.

Continuing The Republic of China,

our selection from A History of China by Wolfram Eberhard published in 1969. The selection is presented in nine easy 5-minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in The Republic of China.

Time: 1905-1948

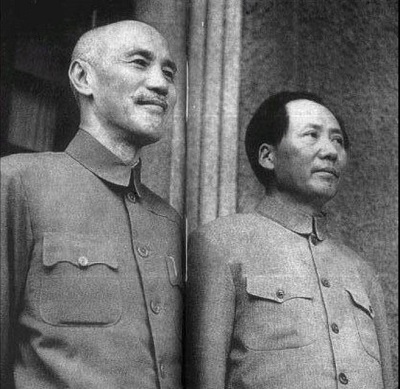

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

3 Second period of the Republic: Nationalist China

With the continued success of the northern campaign, and with Chiang Kai-shek’s southern army at the gates of Shanghai (March 21st, 1927), a decision had to be taken. Should the left wing be allowed to gain the upper hand, and the great capitalists of Shanghai be expropriated as it was proposed to expropriate the gentry? Or should the right wing prevail, an alliance be concluded with the capitalists, and limits be set to the expropriation of landed estates? Chiang Kai-shek, through his marriage with Sun Yat-sen’s wife’s sister, had become allied with one of the greatest banking families. In the days of the siege of Shanghai Chiang, together with his closest colleagues (with the exception of Hu Han-min and Wang Chying-wei, a leader who will be mentioned later), decided on the second alternative. Shanghai came into his hands without a struggle, and the capital of the Shanghai financiers, and soon foreign capital as well, was placed at his disposal, so that he was able to pay his troops and finance his administration. At the same time the Russian advisers were dismissed or executed.

The decision arrived at by Chiang Kai-shek and his friends did not remain unopposed, and he parted from the “left group” (1927) which formed a rival government in Hankow, while Chiang Kai-shek made Nanking the seat of his government (April 1927). In that year Chiang not only concluded peace with the financiers and industrialists, but also a sort of “armistice” with the landowning gentry. “Land reform” still stood on the party program, but nothing was done, and in this way the confidence and cooperation of large sections of the gentry was secured. The choice of Nanking as the new capital pleased both the industrialists and the agrarians: the great bulk of China’s young industries lay in the Yangtze region, and that region was still the principal one for agricultural produce; the landowners of the region were also in a better position with the great market of the capital in their neighborhood.

Meanwhile the Nanking government had succeeded in carrying its dealings with the northern generals to a point at which they were largely outmaneuvered and became ready for some sort of collaboration (1928). There were now four supreme commanders — Chiang Kai-shek, Fêng Yü-hsiang (the “Christian general”), Yen Hsi-shan, the governor of Shansi, and the Muslim Li Chung-yen. Naturally this was not a permanent solution; not only did Chiang Kai-shek’s three rivals try to free themselves from his ever-growing influence and to gain full power themselves, but various groups under military leadership rose again and again, even in the home of the Republic, Canton itself. These struggles, which were carried on more by means of diplomacy and bribery than at arms, lasted until 1936. Chiang Kai-shek, as by far the most skillful player in this game, and at the same time the man who had the support of the foreign governments and of the financiers of Shanghai, gained the victory. China became unified under his dictatorship.

As early as 1928, when there seemed a possibility of uniting China, with the exception of Manchuria, which was dominated by Japan, and when the European powers began more and more to support Chiang Kai-shek, Japan felt that her interests in North China were threatened, and landed troops in Shantung. There was hard fighting on May 3rd, 1928. General Chang Tso-lin, in Manchuria, who was allied to Japan, endeavored to secure a cessation of hostilities, but he fell victim to a Japanese assassin; his place was taken by his son, Chang Hsüeh-liang, who pursued an anti-Japanese policy. The Japanese recognized, however, that in view of the international situation the time had not yet come for intervention in North China. In 1929 they withdrew their troops and concentrated instead on their plans for Manchuria.

Until the time of the “Manchurian incident” (1931), the Nanking government steadily grew in strength. It gained the confidence of the western powers, who proposed to make use of it in opposition to Japan’s policy of expansion in the Pacific sphere. On the strength of this favorable situation in its foreign relations, the Nanking government succeeded in getting rid of one after another of the Capitulations. Above all, the administration of the “Maritime Customs”, that is to say of the collection of duties on imports and exports, was brought under the control of the Chinese government: until then it had been under foreign control. Now that China could act with more freedom in the matter of tariffs, the government had greater financial resources, and through this and other measures it became financially more independent of the provinces. It succeeded in building up a small but modern army, loyal to the government and superior to the still existing provincial armies. This army gained its military experience in skirmishes with the Communists and the remaining generals.

It is true that when in 1931 the Japanese occupied Manchuria, Nanking was helpless, since Manchuria was only loosely associated with Nanking, and its governor, Chang Hsüeh-liang, had tried to remain independent of it. Thus, Manchuria was lost almost without a blow. On the other hand, the fighting with Japan that broke out soon afterwards in Shanghai brought credit to the young Nanking army, though owing to its numerical inferiority it was unsuccessful. China protested to the League of Nations against its loss of Manchuria. The League sent a commission (the Lytton Commission), which condemned Japan’s action, but nothing further happened, and China indignantly broke away from her association with the Western powers (1932-1933). In view of the tense European situation (the beginning of the Hitler era in Germany, and the Italian plans of expansion), the Western powers did not want to fight Japan on China’s behalf, and without that nothing more could be done. They pursued, indeed, a policy of playing off Japan against China, in order to keep those two powers occupied with each other, and so to divert Japan from Indo-China and the Pacific.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

|

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.