We sailed so far south in the torrid zone that we found ourselves under the equinoctial line.

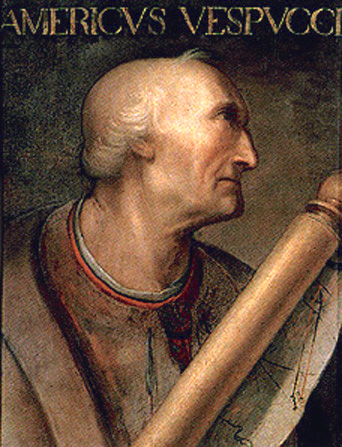

Continuing America’s Namesake’s Second Voyage,

our selection from Mundus Novus by Amerigo Vespucci published in 1507. The selection is presented in five easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in America’s Namesake’s Second Voyage.

Time: 1499

Place: East Coast of Americas

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

As I know, if I remember right, that your excellency understands something of cosmography, I intend to describe to you our progress in our navigation, by the latitude and longitude. We sailed so far to the south that we entered the torrid zone and penetrated the circle of Cancer. You may rest assured that for a few days, while sailing through the torrid zone, we saw four shadows of the sun, as the sun appeared in the zenith to us at midday. I would say that the sun, being in our meridian, gave us no shadow; but this I was enabled many times to demonstrate to all the company, and took their testimony of the fact. This I did on account of the ignorance of the common people, who do not know that the sun moves through its circle of the zodiac. At one time I saw our shadow to the south, at another to the north, at another to the west, and at another to the east, and sometimes, for an hour or two of the day, we had no shadow at all.

We sailed so far south in the torrid zone that we found ourselves under the equinoctial line, and had both poles at the edge of the horizon. Having passed the line, and sailed six degrees to the south of it, we lost sight of the north star altogether, and even the stars of Ursa Minor, or, to speak better, the guardians which revolve about the firmament, were scarcely seen. Very desirous of being the author who should designate the other polar star of the firmament, I lost, many a time, my night’s sleep while contemplating the movement of the stars around the southern pole, in order to ascertain which had the least motion, and which might be nearest to the firmament; but I was not able to accomplish it with such bad nights as I had, and such instruments as I used, which were the quadrant and astrolabe. I could not distinguish a star which had less than ten degrees of motion around the firmament; so that I was not satisfied within myself to name any particular one for the pole of the meridian, on account of the large revolution which they all made around the firmament.

While I was arriving at this conclusion as the result of my investigations, I recollected a verse of our poet Dante, which may be found in the first chapter of his Purgatory, where he imagines he is leaving this hemisphere to repair to the other, and, attempting to describe the antarctic pole, says:

“I turned to the right hand and fixed my mind On the other pole, and saw four stars Not seen before, since the time of our first parents: Joyous appeared the heavens for their glory. Oh, northern lands are widowed Since deprived of such a sight.”

It appears to me that the poet wished to describe in these verses, by the four stars, the pole of the other firmament, and I have little doubt, even now, that what he says may be true. I observed four stars in the figure of an almond, which had but little motion, and if God gives me life and health I hope to go again into that hemisphere, and not to return without observing the pole. In conclusion, I would remark that we extended our navigation so far south that our difference of latitude from the city of Cadiz was sixty degrees and a half, because, at that city, the pole is elevated thirty-five degrees and a half, and we had passed six degrees beyond the equinoctial line. Let this suffice as to our latitude. You must observe that this our navigation was in the months of July, August, and September, when, as you know, the sun is longest above the horizon in our hemisphere, and describes the greatest arch in the day and the least in the night. On the contrary, while we were at the equinoctial line, or near it, within four to six degrees, the difference between the day and the night was not perceptible. They were of equal length, or very nearly so.

As to the longitude, I would say that I found so much difficulty in discovering it that I had to labor very hard to ascertain the distance I had made by means of longitude. I found nothing better, at last, than to watch the opposition of the planets during the night, and especially that of the moon, with the other planets, because the moon is swifter in her course than any other of the heavenly bodies. I compared my observations with the almanac of Giovanni da Monteregio, which was composed for the meridian of the city of Ferrara, verifying them with the calculations in the tables of King Alfonso, and, afterward, with the many observations I had myself made one night with another.

On August 23, 1499 — when the moon was in conjunction with Mars, which, according to the almanac, was to take place at midnight, or half an hour after — I found that when the moon rose to the horizon, an hour and a half after the sun had set, the planet had passed in that part of the east. I observed that the moon was about a degree and some minutes farther east than Mars, and at midnight she was five degrees and a half farther east, a little more or less. So that, making the proportion, if twenty-four hours are equal to three hundred and sixty degrees, what are five hours and a half equal to? I found the result to be eighty-two degrees and a half, which was equal to my longitude from the meridian of the city of Cadiz, then giving to every degree sixteen leagues and two-thirds, which is five thousand four hundred sixty-six miles and two-thirds. The reason why I give sixteen leagues to each degree is because, according to Tolomeo and Alfagrano, the earth turns twenty-four thousand miles, which is equal to six thousand leagues, which, being divided by three hundred sixty degrees, gives to each degree sixteen leagues and two-thirds. This calculation I certified many times conjointly with the pilots, and found it true and good.

It appears to me, most excellent Lorenzo, that by this voyage most of those philosophers are controverted who say that the torrid zone cannot be inhabited on account of the great heat. I have found the case to be quite the contrary. I have found that the air is fresher and more temperate in that region than beyond it, and that the inhabitants are also more numerous here than they are in the other zones, for reasons which will be given below. Thus it is certain that practice is of more value than theory.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.