This series has five easy 5 minute installments. This first installment: Thirteen Hundred Leagues SW of Cadiz.

Introduction

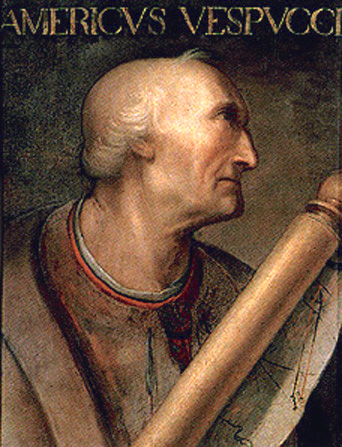

It was the claim of Amerigo Vespucci that he accompanied four expeditions to the New World, and that he wrote a narrative of each voyage. According to Amerigo, the first expedition sailed from Spain in 1497; the second, of which his own account is here given, in 1499; both by order of King Ferdinand. Grave doubt has been thrown upon the first of these expeditions, the sole authority for which is Vespucci himself.

The name America was given to two continents in honor of this naval astronomer on the authority of an account of his travels published in 1507, in which he is represented as having reached the mainland in 1497. The justice of this naming has always been and still remains a matter of warm dispute among historical critics.

But at the age of almost fifty — he was born in Florence in 1451 — Vespucci unquestionably promoted and made a voyage to the New World. In May, 1499, he sailed from Spain with Alonzo de Ojeda, who commanded four vessels. During the summer they explored the coast of Venezuela (“Little Venice”), a name first given by Ojeda to a gulf of the Caribbean Sea, on the shores of which were cabins built on piles over the water, reminding him of Venice in Italy. Ojeda, who was but little acquainted with navigation, entered upon this voyage more as a marauding enterprise than an expedition of discovery, and he gladly availed himself of Amerigo’s scientific ability. Vespucci was also able to command the financial support of his wealthy acquaintances. It is said that many of the former sailors of Columbus shipped with this expedition.

The following account was written by Amerigo in a letter to Lorenzo Pier Francesco, of the Medici family of Florence, from whom Vespucci had held certain business commissions in Spain. Respecting this letter an Italian critic observes that “it is the most ancient known writing of Amerigo relating to his voyages to the New World, having been composed within a month after his return from his second voyage, and remaining buried in our archives for a long time. It is a precious monument, for without it we should have been left in ignorance of the great additions which he made to astronomical science. The most rigorous examination of this letter cannot bring to light the least circumstance proving anything for or against the accuracy of his first voyage. The diffidence with which he commences the matter is, however, a strong indication that he had previously written an account of his first voyage to the same Lorenzo de’ Medici, to whom he addressed this communication.”

This selection is from Mundus Novus by Amerigo Vespucci published in 1507. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Amerigo Vespucci (1454-1512) was the great explorer who wrote this account of his second voyage.

Time: 1499

Place: East Coast of Americas

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

MOST EXCELLENT AND DEAR LORD:

It is a long time since I have written to your excellency, and for no other reason than that nothing has occurred to me worthy of being commemorated. This present fetter will inform you that about a month ago I arrived from the Indies, by the way of the great ocean, brought, by the grace of God, safely to this city of Seville. I think your excellency will be gratified to learn the result of my voyage, and the most surprising things which have been presented to my observation. If I am somewhat tedious, let my letter be read in your more idle hours, as fruit is eaten after the cloth is removed from the table. Your excellency will please to note that, commissioned by his highness the King of Spain, I set out with two small ships, on May 18, 1499, on a voyage of discovery to the southwest, by way of the great ocean, and steered my course along the coast of Africa, until I reached the Fortunate Islands, which are now called the Canaries. After having provided ourselves with all things necessary, first offering our prayers to God, we set sail from an island which is called Gomera, and, turning our prows southwardly, sailed twenty-four days with a fresh wind, without seeing any land.

At the end of these twenty-four days we came within sight of land, and found that we had sailed about thirteen hundred leagues, and were at that distance from the city of Cadiz, in a southwesterly direction. When we saw the land we gave thanks to God, and then launched our boats, and, with sixteen men, went to the shore, which we found thickly covered with trees, astonishing both on account of their size and their verdure, for they never lose their foliage. The sweet odor which they exhaled — for they are all aromatic — highly delighted us, and we were rejoiced in regaling our nostrils.

We rowed along the shore in the boats, to see if we could find any suitable place for landing, but, after toiling from morning till night, we found no way or passage which we could enter and disembark. We were prevented from doing so by the lowness of the land, and by its being so densely covered with trees. We concluded, therefore, to return to the ships, and make an attempt to land in some other spot.

We observed one remarkable circumstance in these seas.

It was that at fifteen leagues from the land we found the water fresh like that of a river, and we filled all our empty casks with it. Having returned to our ships, we raised anchor and set sail, turning our prows southwardly, as it was my intention to see whether I could sail around a point of land which Ptolemy calls the Cape of Cattegara, which is near the Great Bay. In my opinion it was not far from it, according to the degrees of latitude and longitude, which will be stated hereafter. Sailing in a southerly direction along the coast, we saw two large rivers issuing from the land, one running from west to east, and being four leagues in width, which is sixteen miles; the other ran from south to north, and was three leagues wide. I think that these two rivers, by reason of their magnitude, caused the freshness of the water in the adjoining sea. Seeing that the coast was invariably low, we determined to enter one of these rivers with the boats, and ascend it till we either found a suitable landing-place or an inhabited village.

Having prepared our boats, and put in provision for four days, with twenty men well armed, we entered the river, and rowed nearly two days, making a distance of about eighteen leagues. We attempted to land in many places by the way, but found the low land still continuing, and so thickly covered with trees that a bird could scarcely fly through them. While thus navigating the river, we saw very certain indications that the inland parts of the country were inhabited; nevertheless, as our vessels remained in a dangerous place in case an adverse wind should arise, we concluded, at the end of two days, to return.

Here we saw an immense number of birds, of various forms and colors; a great number of parrots, and so many varieties of them that it caused us great astonishment. Some were crimson-colored, others of variegated green and lemon, others entirely green, and others, again, that were black and flesh-colored. Oh! the song of other species of birds, also, was so sweet and so melodious, as we heard it among the trees, that we often lingered, listening to their charming music. The trees, too, were so beautiful and smelled so sweetly that we almost imagined ourselves in a terrestrial paradise; yet not one of those trees, or the fruit of them, was similar to the trees or fruit in our part of the world. On our way back we saw many people, of various descriptions, fishing in the river.

Having arrived at our ships, we raised anchor and set sail, still continuing in a southerly direction, and standing off to sea about forty leagues. While sailing on this course, we encountered a current which ran from southeast to northwest; so great was it, and ran so furiously, that we were put into great fear, and were exposed to great peril. The current was so strong that the Strait of Gibraltar and that of the Faro of Messina appeared to us like mere stagnant water in comparison with it. We could scarcely make any headway against it, though we had the wind fresh and fair. Seeing that we made no progress, or but very little, and the danger to which we were exposed, we determined to turn our prows to the northwest.

| Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.