The settlers revolted against its authority and appealed to Virginia.

Continuing Daniel Boone Settles Kentucky,

our selection from The Winning of the West, Vol. 1 by Theodore Roosevelt published in 1889. The selection is presented in seven easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Daniel Boone Settles Kentucky.

Time: 1775

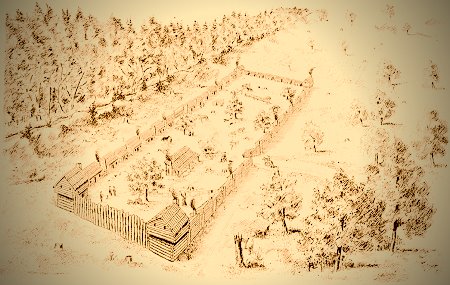

Place: Boonesborough, Kentucky

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

As Henderson pointed out, the game was the sole dependence of the first settlers, who, most of the time, lived solely on wild meat, even the parched corn having been exhausted; and without game the newcomers could not have stayed in the land a week.[1] Accordingly he advised the enactment of game-laws; and he was especially severe in his comments upon the “foreigners” who came into the country merely to hunt, killing off the wild beasts, and taking their skins and furs away, for the benefit of persons not concerned in the settlement. This last point is curious as showing how instantly and naturally the colonists succeeded not only to the lands of the Indians, but also to their habits of thought; regarding intrusion by outsiders upon their hunting-grounds with the same jealous dislike so often shown by their red-skinned predecessors.

[1: “Our game, the only support of life amongst many of us, and without which the country would be abandoned ere to-morrow.” Henderson’s address.]

Henderson also outlined some of the laws he thought it advisable to enact, and the Legislature followed his advice. They provided for courts of law, for regulating the militia, for punishing criminals, fixing sheriffs’ and clerks’ fees, and issuing writs of attachment.[2] One of the members was a clergyman: owing to him a law was passed forbidding profane swearing or Sabbath-breaking; a puritanical touch which showed the mountain rather than the seaboard origin of the men settling Kentucky. The three remaining laws the Legislature enacted were much more characteristic, and were all introduced by the two Boones — for Squire Boone was still the companion of his brother. As was fit and proper, it fell to the lot of the greatest of backwoods hunters to propose a scheme for game protection, which the Legislature immediately adopted; and his was likewise the “act for preserving the breed of horses,” — for, from the very outset, the Kentuckians showed the love for fine horses and for horse-racing which has ever since distinguished them. Squire Boone was the author of a law “to protect the range”; for the preservation of the range or natural pasture over which the branded horses and cattle of the pioneers ranged at will, was as necessary to the welfare of the stock as the preservation of the game was to the welfare of the men. In Kentucky the range was excellent, abounding not only in fine grass, but in cane and wild peas, and the animals grazed on it throughout the year. Fires sometimes utterly destroyed immense tracts of this pasture, causing heavy loss to the settlers; and one of the first cares of pioneer legislative bodies was to guard against such accidents.

[2: Journal of the Proceedings of the House of Delegates or Representatives of the Colony of Transylvania.]

It was likewise stipulated that there should be complete religious freedom and toleration for all sects. This seems natural enough now, but in the eighteenth century the precedents were the other way. Kentucky showed its essentially American character in nothing more than the diversity of religious belief among the settlers from the very start. They came almost entirely from the backwoods mountaineers of Virginia, Pennsylvania, and North Carolina, among whom the predominant faith had been Presbyterianism; but from the beginning they were occasionally visited by Baptist preachers,[3] whose creed spread to the borders sooner than Methodism; and among the original settlers of Harrodsburg were some Catholic Marylanders.[4] The first service ever held in Kentucky was by a clergyman of the Church of England, soon after Henderson’s arrival; but this was merely owing to the presence of Henderson himself, who, it must be remembered, was not in the least a backwoods product. He stood completely isolated from the other immigrants during his brief existence as a pioneer, and had his real relationship with the old English founders of the proprietary colonies, and with the more modern American land speculators, whose schemes are so often mentioned during the last half of the eighteenth century. Episcopacy was an exotic in the backwoods; it did not take real root in Kentucky till long after that commonwealth had emerged from the pioneer stage.

[3: Possibly in 1775, certainly in 1776; MS. autobiography of Rev. Wm. Hickman. In Durrett’s library.]

[4: “Life of Rev. Charles Nerinckx,” by Rev. Camillus P. Maes, Cincinnati, 1880, p. 67.]

When the Transylvanian Legislature dissolved, never to meet again, Henderson had nearly finished playing his short but important part in the founding of Kentucky. He was a man of the seacoast regions, who had little in common with the backwoodsmen by whom he was surrounded; he came from a comparatively old and sober community, and he could not grapple with his new associates; in his journal he alludes to them as a set of scoundrels who scarcely believed in God or feared the devil. A British friend[5] of his, who at this time visited the settlement, also described the pioneers as being a lawless, narrow-minded, unpolished, and utterly insubordinate set, impatient of all restraint, and relying in every difficulty upon their individual might; though he grudgingly admitted that they were frank, hospitable, energetic, daring, and possessed of much common-sense. Of course it was hopeless to expect that such bold spirits, as they conquered the wilderness, would be content to hold it even at a small quit-rent from Henderson. But the latter’s colony was toppled over by a thrust from without before it had time to be rent in sunder by violence from within.

[5: Smyth, p. 330.]

Transylvania was between two millstones. The settlers revolted against its authority, and appealed to Virginia; and meanwhile Virginia, claiming the Kentucky country, and North Carolina as mistress of the lands round the Cumberland, proclaimed the purchase of the Transylvanian proprietors null and void as regards themselves, though valid as against the Indians. The title conveyed by the latter thus inured to the benefit of the colonies; it having been our policy, both before and since the Revolution, not to permit any of our citizens to individually purchase lands from the savages.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.