Today’s installment concludes Union of Denmark Sweden and Norway,

our selection from The Scandinavian Races by Paul C. Sinding published in 1875.

For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Union of Denmark Sweden and Norway.

Time: June 17, 1397

Place: Kalmar, Sweden

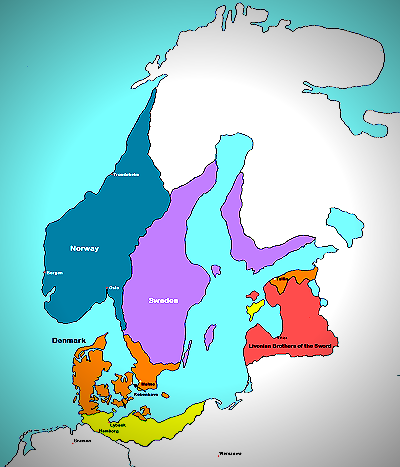

CC BY-SA 3.0 image from Wikipedia.

The year following, the Queen stormed the important city of Kalmar, yet siding with the imprisoned King. She made several wise alliances with Richard II of England, and other potentates, and concluded a truce for two years with the princes of Mecklenburg, and the cities of Rostock and Wismar, which had begun to raise fresh levies in favor of the unfortunate Albert. This period expired, she laid siege to Stockholm and other fortified places, of which John, Duke of Mecklenburg, and other friends of the imprisoned King had become masters. But the cause of Albert was little forwarded, and Margaret gained ground every day. She compelled the capital to surrender to her and do homage to her as its sovereign; whereafter a peremptory peace was concluded on Good Friday, which restored tranquillity to the three kingdoms. The imprisoned King and his son were delivered up to the Hanseatic towns, and they obtained their liberty for sixty thousand ounces of silver, upon condition that they should resign all claims to Sweden if the amount were not paid within three years. As soon as the King and his son were delivered to the deputies, they solemnly swore to a strict observance of this article, the Hanse towns engaging themselves to guarantee the treaty. The money, however, not being paid by the stipulated time, Margaret became undisputed sovereign of Sweden, the third Scandinavian kingdom.

About this time the “Victuals Brethren,” so called because they brought victuals from the Hanse towns to Stockholm while besieged, began to imperil Denmark, plundering the Danish and Norwegian coasts, and destroying all commercial business along the Baltic. But Margaret ordered the harbors of the maritime towns to be blockaded, thus putting a quick stop to their cruelties and piracies. The Queen’s principal care was now to visit the different provinces, to administer justice and redress grievances of every kind. Among other salutary regulations, the affairs of commerce were not forgotten. It was, for instance, decreed that all manner of assistance should be given to foreign merchants and sailors, particularly in case of misfortune and shipwreck, without expectation of reward; and that all pirates should be treated with the greatest rigor.

Eric of Pomerania was, as we have said, elected to be king of Denmark and Norway after Margaret’s death. But wishing to have him also elected her successor to the Swedish throne, Margaret brought him to Sweden, and introduced him to the deputies, one by one, whom she requested to confirm his election to the succession. The majesty of the Queen’s person, the strength of her arguments, and the sweetness of her eloquence gained over the deputies, who, on July 22, 1396, elected him at Morastone by Upsala, to succeed her also in Sweden. But Margaret, soon discovering his inability and impetuousness, took pains to remedy these defects, as much as possible, by procuring for him as a wife the intelligent and virtuous princess Philippa, a daughter of Henry V of England, and shortly after had got Catharine, her niece and Eric’s sister, married to Prince John, a son of the German emperor Ruprecht; John being promised the Scandinavian crowns if Eric of Pomerania should die childless. Thus having strengthened and consolidated her power by influential connections and relationships, the Queen, upon whose head the three northern crowns were actually united, now proceeded to realize the great plan she had long cherished — to get a fundamental law established for a perpetual union of the three large Scandinavian kingdoms. The realization of this purpose immortalized her, securing for her the admiration of the world, whose most eminent historians do not hesitate to surname her the “Great,” and to compare her with the loftiest Greek and Roman heroes and statesmen.

On June 17, 1397, Margaret summoned to an assembly at Kalmar, in the province of Smaland, Sweden, the clergy and the nobility of Denmark, Norway, and Sweden, and established, by their aid and consent, a fundamental law. This was the law so celebrated in the North under the name of the “Union of Kalmar,” and which afterward gave birth to wars between Sweden and Denmark that lasted a whole century. It consisted of three articles. The first provided that the three kingdoms should thenceforward have but one and the same king, who was to be chosen successively by each of the kingdoms. The second article imposed upon the sovereign the obligation of dividing his time equally between the three kingdoms. The third, and most important, decreed that each kingdom should retain its own laws, customs, senate, and privileges of every kind; that the highest officers should be natives; that any alliance concluded with foreign potentates should be obligatory upon all three kingdoms when approved by the council of one kingdom; and that, after the death of the King, his eldest son, or, if the King died childless, then another wise, intelligent, and able prince, should be chosen common monarch; and if anyone, because of high treason, was banished from one kingdom, then he should be banished from them all. A month after, on the Queen’s birthday, July 13th, a legitimate charter was drawn up, to which the Queen subscribed and put her seal; on which occasion Eric of Pomerania was anointed and crowned by the archbishops of Upsala and Lund as king of Denmark, Norway, and Sweden. The Te Deum was sung in the churches of Kalmar, the assembly crying out: “Hæcce unio esto perpetua! Longe, longe, longe, vivat Margarethe, regina Daniæ, Norvegiæ et Sveciæ!”

This strict union of the three large states became a potent bulwark for their security, and made them, in more than one century, the arbiter of the European system; the three nations of the northern peninsula presenting a compact and united front, that could bid defiance to any foreign aggression.

Although Eric of Pomerania was elected king, and in 1407 passed his minority, Margaret continued governing until the day of her death. “You have done all well,” wrote the people to her, “and we value your services so highly that we would gladly grant you everything.” The union of the three Scandinavian kingdoms having been established in Kalmar, all her efforts were now aimed at regaining the duchy of Schleswig, which circumstances had compelled her to resign to Gerhard IV, Count of Holstein. For such a reunion with Schleswig a favorable opportunity appeared, when Gerhard was killed in an expedition against the Ditmarshers, leaving behind three sons in minority. Elizabeth, Gerhard’s widow, fled to Margaret for succor against her violent brother-in-law, Bishop Henry of Osnabrueck. Margaret, fond of fishing in foul water, was very willing to help her, but availed herself of the opportunity to annex successively different parts of Schleswig.

The dethroned Swedish King, Albert, never able to forget his anger toward Margaret or her severity against him, and continually cherishing a hope of reascending the Swedish throne, and considering the Union of Kalmar a breach of peace, contrived to make the Swedish people displeased with her, and thought it a suitable time to revolt from her dominion. He established a strong camp before Visby, the capital of the island of Gulland, having six thousand foot and, at some distance, nine thousand horse. Determined to engage before their junction could take place, the Queen’s commander-in-chief, Abraham Broder, immediately advanced until in sight of the enemy, and then endeavored to gain possession of Visby and the ground nearby. In this he was so far successful that Albert and his army had to leave the camp and conclude a truce. But nevertheless he did not till after a lapse of seven years give up his hope of remounting the throne of Sweden, making a final peace with Margaret, and henceforward living in Gadebush, Mecklenburg, where in 1412 he closed his inglorious life.

Soon after, October 27th, Queen Margaret died on board a ship in the harbor of Flensburg, at the age of fifty-nine, after an active and notable reign of thirty-seven years. Her funeral was attended with the greatest solemnity, and her corpse was brought to the Cathedral of Roeskilde, where Eric of Pomerania, her successor, in 1423, caused her likeness to be carved in alabaster. Her acts show her character. She displayed judiciousness united with circumspection; wisdom in devising plans, and perseverance in executing them; skill in gaining the confidence of the clergy and peasantry, and thereby counterbalancing the imperious nobility. On the whole she applied herself to the civilization of her three kingdoms, and to their improvement by excellent laws, the great aim of which was to undermine the nobility. She pursued the plan of her great father to recall all rights to the crown lands, which during the reign of her weak and inefficient predecessors had been granted to the nobility. The prosecution of this plan for the perfect subversion of the feudal aristocracy was unfortunately interrupted by her death; her imprudent and weak successor having no power to restrain the turbulent spirit of a factious nobility.

| <—Previous | Master List |

More information on Union of Denmark Sweden and Norway here and here and below.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.