This series has two easy 5 minute installments. This first installment: Margaret I of Denmark Takes Charge.

Introduction

Canute the Great, King of England and Denmark, by successful wars added almost the whole of Norway to his dominions. At his death in 1035 his kingdoms were divided, and fell into anarchy and discord for two centuries, until the tyrant Black Geert, who had driven out Christopher II, and been for fourteen years the virtual sovereign of Denmark, was assassinated by the Danish patriot Niels Ebbeson.

Christopher’s third son, Waldemar, surnamed Atterdag, because he used to say when a misfortune happened, “To-morrow it is again day,” was recalled from Bavaria and crowned king as Waldemar IV. He commenced at once with vigor and marked success the improvement of the internal conditions of the country, and strove to encompass his chief ambition, the reunion of the ancient Danish possessions.

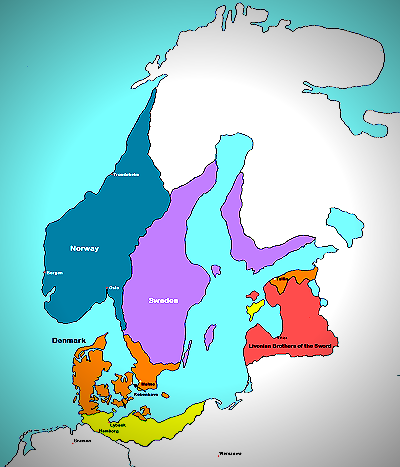

By marrying his daughter Margaret to Hakon VI, King of Norway and son of Magnus Smek, King of Sweden, Waldemar laid a basis for a junction of the three great Scandinavian kingdoms. The union was realized under the administration of his illustrious and sagacious daughter, Margaret, known as the “Semiramis of the North.”

This selection is from The Scandinavian Races by Paul C. Sinding (1812-1887) published in 1875. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Time: June 17, 1397

Place: Kalmar, Sweden

CC BY-SA 3.0 image from Wikipedia.

Waldemar Atterdag left no direct male issue. But his two grandsons, Albert the Younger, of Mecklenburg, a son of Ingeborg, Waldemar’s eldest daughter, and of Henry of Mecklenburg; and Olaf, a son of Margaret, his younger daughter, and of Hakon VI of Norway, were now claiming the hereditary succession to the throne. One party declared for Olaf, but, as he was the son of the younger daughter, his claim was very doubtful. But because the house of Mecklenburg had acted with hostility toward Denmark, and Olaf had expectation of Norway and claims to the crown of Sweden, as a grandson of Magnus Smek, Denmark was, by his election, in hopes of one day seeing the three crowns united on the same head. It was therefore not long before this important affair was determined. The preference was given Olaf, who, although only six years of age, was, under the name of Olaf V, elected king of Denmark, under the guardianship of Margaret his mother; and after the death of his father Hakon VI, he became also king of Norway, the two kingdoms thus being united. This union, till the expiration of four hundred and thirty-four years, was not dissolved. When Olaf V, seven years after, died in Falsterbo, both kingdoms elected Margaret their queen, though custom had not yet authorized the election of a female.

During the reign of this great Princess, who deservedly has been called the “Semiramis of the North,” Denmark and Norway exercised in Europe an influence the effects of which were long felt throughout the Scandinavian countries with their vast extent and rival races. She united wisdom and policy with courage and determination, had strength of mind to preserve her rectitude without deviation, and her efforts were crowned by divine Providence with success. She is justly considered one of the most illustrious female rulers in history. Her renown even reached the Byzantine emperor Emanuel Palæologus, who called her Regina sine exemplo maxima. But under her successors — destitute of her high sense of duty, great ability, and consistent virtue — her triumphs proved a snare instead of a blessing. The great union she created dissolved in a short time, and its downfall was as sudden as its elevation had been extraordinary. She was born in 1353. Her father was, as we have seen, Waldemar Atterdag, her mother Queen Hedevig, and she became queen of Denmark and Norway in 1387. She was no sooner elected queen of Denmark, and homaged on the hill of Sliparehog, near Lund, in Ringsted, Odensee, and Wiborg, than she sailed to Norway to receive their homage. But a remarkable occurrence is mentioned by historians as occurring about this time. A report prevailed that King Olaf, the Queen’s son, was not dead; it was propagated by the nobility, and very likely set on foot by them, in order to punish Margaret for her liberality to the clergy. An impostor claimed the crown of Denmark and Norway, and gained credit every day by making discoveries which could only be known to Olaf and his mother. Margaret, however, proved him to be a son of Olaf’s nurse. Olaf had a large wart between his shoulders — a mark which did not appear on the impostor. The false Olaf was seized, broken on the wheel, and publicly burned at a place between Falsterbo and Skanor, in Sweden, and Margaret continued uninterruptedly her regency.

But the Queen, not wishing to contract a new marriage, and comprehending the importance of having a successor elected to the throne, proposed her nephew, Eric, Duke of Pomerania. This proposal the clergy and nobility approved, and they elected him to be king of Denmark and Norway after Margaret’s death. Meanwhile Albert, King of Sweden, having, on account of his preference given to German favorites, incurred the hatred of his people, the Swedes requested Margaret to assist them against him, which she promised to do if they in return would make her queen of Sweden. Moreover, Albert had highly offended the Danish Queen; had, though hardly able to govern his own kingdom, assumed the title “king of Denmark,” and laid claim to Norway, too; and when she blamed him for it he had answered her disdainfully. In a letter he had used foul and abusive language, calling her “a king without breeches,” and the “abbot’s concubine” (abbedfrillen), on account of her particular attachment to a certain abbot of Soro, who was her spiritual director. It is, however, true, that her intimacy with this monk gave room for some suspicion that her privacies with him were not all employed about the care of her soul. Afterward, to ridicule her yet more, King Albert sent her a hone to sharpen her needles, and swore not to put on his nightcap until she had yielded to him. But under perilous circumstances Margaret was never at a loss how to act. She acted here with the utmost prudence, trying first to gain the favor of the peers of the state, and solemnly promising to rule according to the Swedish laws. War now broke out between Albert and Margaret, whose army was commanded by Jvar Lykke. The encounter of the two armies — about twelve thousand men on each side — took place at Falkoping, September 21, 1388. A furious battle was fought, in which the victory for a long while hung in suspense. But Margaret’s good fortune prevailed; Albert was routed and his army cut to pieces, and Margaret was now mistress of Sweden.

While this was passing, the Queen tarried in Wordingborg Sjelland, ardently desiring to learn the result. But no sooner did she hear that the victory was gained, and the Swedish King and his son Eric taken prisoners, than she hastened to Bahus, in Sweden, where the King and his son were brought before her. Lost in joy and amazement at having her enemy in her power, the Queen now retorted upon King Albert with revilings, and she made him wear a large nightcap of paper — a retaliation proportioned to his offensive words. He and his son were thereupon brought to Lindholm, a castle in Skane, where they were kept prisoners for seven years. When they entered the castle, a dark, square room was assigned them, and when the King said, “I hope that this torture against a crowned head will only last a few days,” the jailer replied: “I grieve to say that the Queen’s orders are to the contrary; anger not the Queen by any bravado, else you will be placed in the irons, and if these fail we can have recourse to sharper means.” To the excessive self-love, intemperance, conceitedness, and want of foresight which had characterized all his actions, the unhappy Albert had to ascribe his present situation.

| Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here and below.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.