Today’s installment concludes Daniel Boone Settles Kentucky,

our selection from The Winning of the West, Vol. 1 by Theodore Roosevelt published in 1889.

If you have journeyed through the installments of this series so far, just one more to go and you will have completed a selection from the great works of seven thousand words. Congratulations! For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Daniel Boone Settles Kentucky.

Time: 1775

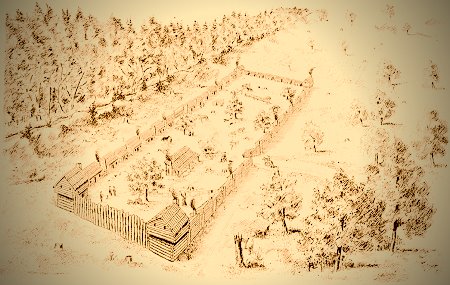

Place: Boonesborough, Kentucky

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

Lord Dunmore denounced Henderson and his acts; and it was in vain that the Transylvanians appealed to the Continental Congress, asking leave to send a delegate thereto, and asserting their devotion to the American cause; for Jefferson and Patrick Henry were members of that body, and though they agreed with Lord Dunmore in nothing else, were quite as determined as he that Kentucky should remain part of Virginia. So Transylvania’s fitful life flickered out of existence; the Virginia Legislature in 1778, solemnly annulling the title of the company, but very properly recompensing the originators by the gift of two hundred thousand acres.[1] North Carolina pursued a precisely similar course; and Henderson, after the collapse of his colony, drifts out of history.

[1: Gov. James T. Morehead’s “address” at Boonsborough, in 1840 (Frankfort, Ky., 1841).]

Boone remained to be for some years one of the Kentucky leaders. Soon after the fort at Boonesboro was built, he went back to North Carolina for his family, and in the fall returned, bringing out a band of new settlers, including twenty-seven “guns” — that is, rifle-bearing men, — and four women, with their families, the first who came to Kentucky, though others shortly followed in their steps.[2] A few roving hunters and daring pioneer settlers also came to his fort in the fall; among them, the famous scout, Simon Kenton, and John Todd,[3] a man of high and noble character and well-trained mind, who afterwards fell by Boon’s side when in command at the fatal battle of Blue Licks. In this year also Clark[4] and Shelby[5] first came to Kentucky; and many other men whose names became famous in frontier story, and whose sufferings and long wanderings, whose strength, hardihood, and fierce daring, whose prowess as Indian fighters and killers of big game, were told by the firesides of Kentucky to generations born when the elk and the buffalo had vanished from her borders as completely as the red Indian himself. Each leader gathered round him a little party of men, who helped him build the fort which was to be the stronghold of the district. Among the earliest of these town-builders were Hugh McGarry, James Harrod, and Benjamin Logan. The first named was a coarse, bold, brutal man, always clashing with his associates (he once nearly shot Harrod in a dispute over work). He was as revengeful and foolhardy as he was daring, but a natural leader in spite of all. Soon after he came to Kentucky his son was slain by Indians while out boiling sugar from the maples; and he mercilessly persecuted all redskins for ever after. Harrod and Logan were of far higher character, and superior to him in every respect. Like so many other backwoodsmen, they were tall, spare, athletic men, with dark hair and grave faces. They were as fearless as they were tireless, and were beloved by their followers. Harrod finally died alone in the wilderness, nor was it ever certainly known whether he was killed by Indian or white man, or perchance by some hunted beast. The old settlers always held up his memory as that of a man ever ready to do a good deed, whether it was to run to the rescue of someone attacked by Indians, or to hunt up the strayed plough-horse of a brother settler less skillful as a woodsman; yet he could hardly read or write. Logan was almost as good a woodsman and individual fighter, and in addition was far better suited to lead men. He was both just and generous. His father had died intestate, so that all of his property by law came to Logan, who was the eldest son; but the latter at once divided it equally with his brothers and sisters. As soon as he came to Kentucky he rose to leadership, and remained for many years among the foremost of the commonwealth founders.

[1: _Do._, p. 51. Mrs. Boon, Mrs. Denton, Mrs. McGarry, Mrs. Hogan; all were from the North Carolina backwoods; their ancestry is shown by their names. They settled in Boonesborough and Harrodsburg.]

[2: Like Logan he was born in Pennsylvania, of Presbyterian Irish stock. He had received a good education.]

[3: Morehead, p. 52.]

[4: Shelby’s MS. autobiography, in Durrett’s Library at Louisville.]

All this time there penetrated through the somber forests faint echoes of the strife the men of the seacoast had just begun against the British king. The rumors woke to passionate loyalty the hearts of the pioneers; and a roaming party of hunters, when camped on a branch[5] of the Elkhorn, by the hut of one of their number, named McConnell, called the spot Lexington, in honor of the memory of the Massachusetts minute-men, about whose death and victory they had just heard.[6]

[5: These frontiersmen called a stream a “run,” “branch,” “creek,” or “fork,” but never a “brook,” as in the northeast.]

[6: “History of Lexington,” G. W. Ranck, Cincinnati, 1872, p. 19. The town was not permanently occupied till four years later.]

By the end of 1775 the Americans had gained firm foothold in Kentucky. Cabins had been built and clearings made; there were women and children in the wooden forts, cattle grazed on the range, and two or three hundred acres of corn had been sown and reaped. There were perhaps some three hundred men in Kentucky, a hardy, resolute, strenuous band. They stood shoulder to shoulder in the wilderness, far from all help, surrounded by an overwhelming number of foes. Each day’s work was fraught with danger as they warred with the wild forces from which they wrung their living. Around them on every side lowered the clouds of the impending death struggle with the savage lords of the neighboring lands.

These backwoodsmen greatly resembled one another; their leaders were but types of the rank and file, and did not differ so very widely from them; yet two men stand out clearly from their fellows. Above the throng of wood-choppers, game-hunters, and Indian fighters loom the sinewy figures of Daniel Boon and George Rogers Clark.

| <—Previous | Master List |

This ends our series of passages on Daniel Boone Settles Kentucky by Theodore Roosevelt from his book The Winning of the West, Vol. 1 published in 1889. This blog features short and lengthy pieces on all aspects of our shared past. Here are selections from the great historians who may be forgotten (and whose work have fallen into public domain) as well as links to the most up-to-date developments in the field of history and of course, original material from yours truly, Jack Le Moine. – A little bit of everything historical is here.

More information on Daniel Boone Settles Kentucky here and here and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.