They were scattered over large areas, and, as elsewhere in the southwest, the county and not the town became the governmental unit.

Continuing Daniel Boone Settles Kentucky,

our selection from The Winning of the West, Vol. 1 by Theodore Roosevelt published in 1889. The selection is presented in seven easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Daniel Boone Settles Kentucky.

Time: 1775

Place: Boonesborough, Kentucky

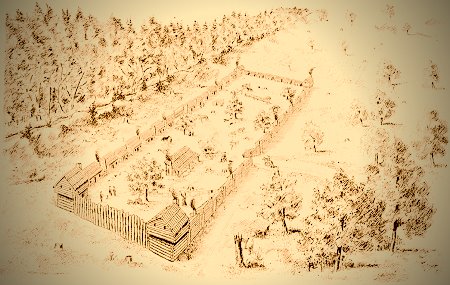

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

The fort was in shape a parallelogram, some two hundred and fifty feet long and half as wide. It was more completely finished than the majority of its kind, though little or no iron was used in its construction. At each corner was a two-storied loop-holed block-house to act as a bastion. The stout log-cabins were arranged in straight lines, so that their outer sides formed part of the wall, the spaces between them being filled with a high stockade, made of heavy squared timbers thrust upright into the ground, and bound together within by a horizontal stringer near the top. They were loop-holed like the block-houses. The heavy wooden gates, closed with stout bars, were flanked without by the block-houses and within by small windows cut in the nearest cabins. The houses had sharp, sloping roofs, made of huge clapboards, and these great wooden slabs were kept in place by long poles, bound with withes to the rafters. In case of dire need each cabin was separately defensible. When danger threatened, the cattle were kept in the open space in the middle.

Three other similar forts or stations were built about the same time as Boonesborough, namely: Harrodstown, Boiling Springs, and St. Asaphs, better known as Logan’s Station, from its founder’s name. These all lay to the southwest, some thirty odd miles from Boonesboroug. Every such fort or station served as the rallying-place for the country round about, the stronghold in which the people dwelt during time of danger; and later on, when all danger had long ceased, it often remained in changed form, growing into the chief town of the district. Each settler had his own farm besides, often a long way from the fort, and it was on this that he usually intended to make his permanent home. This system enabled the inhabitants to combine for defense, and yet to take up the large tracts of four to fourteen hundred acres,[1] to which they were by law entitled. It permitted them in time of peace to live well apart, with plenty of room between, so that they did not crowd one another — a fact much appreciated by men in whose hearts the spirit of extreme independence and self-reliance was deeply ingrained. Thus the settlers were scattered over large areas, and, as elsewhere in the southwest, the county and not the town became the governmental unit. The citizens even of the smaller governmental divisions acted through representatives, instead of directly, as in the New England town-meetings.[2] The center of county government was of course the county courthouse.

[1: Four hundred acres were gained at the price of $2.50 per 100 acres, by merely building a cabin and raising a crop of corn; and every settler with such a “cabin right” had likewise a preemption right to 1,000 acres adjoining, for a cost that generally approached forty dollars a hundred.]

[2: In Mr. Phelan’s scholarly “History of Tennessee,” pp. 202-204, etc., there is an admirably clear account of the way in which Tennessee institutions (like those of the rest of the Southwest) have been directly and without a break derived from English institutions; whereas many of those of New England are rather pre-Normanic revivals, curiously paralleled in England as it was before the Conquest.]

Henderson, having established a land agency at Boonesboro, at once proceeded to deed to the Transylvania colonists entry certificates of surveys of many hundred thousand acres. Most of the colonists were rather doubtful whether these certificates would ultimately prove of any value, and preferred to rest their claims on their original cabin rights; a wise move on their part, though in the end the Virginia Legislature confirmed Henderson’s sales in so far as they had been made to actual settlers. All the surveying was of course of the very rudest kind. Only a skilled woodsman could undertake the work in such a country; and accordingly much of it devolved on Boone, who ran the lines as well as he could, and marked the trees with his own initials, either by powder or else with his knife.[3] The State could not undertake to make the surveys itself, so it authorized the individual settler to do so. This greatly promoted the rapid settlement of the country, making it possible to deal with land as a commodity, and outlining the various claims; but the subsequent and inevitable result was that the sons of the settlers reaped a crop of endless confusion and litigation.

[3: Boone’s deposition, July 29, 1795.]

It is worth mentioning that the Transylvania company opened a store at Boonesboro. Powder and lead, the two commodities most in demand, were sold respectively for $2.66-2/3 and 16-2/3 cents per pound. The payment was rarely made in coin; and how high the above prices were may be gathered from the fact that ordinary labor was credited at 33-1/3 cents per day while fifty cents a day was paid for ranging, hunting, and working on the roads.

[Mann Butler, p. 31.]

Henderson immediately proceeded to organize the government of his colony, and accordingly issued a call for an election of delegates to the Legislature of Transylvania, each of the four stations mentioned above sending members. The delegates, seventeen in all, met at Boonesboro and organized the convention on the 23d of May. Their meetings were held without the walls of the fort, on a level plain of white clover, under a grand old elm. Beneath its mighty branches a hundred people could without crowding find refuge from the noon-day sun; it was a fit council-house for this pioneer legislature of game hunters and Indian fighters.

[Henderson’s Journal. The beauty of the elm impressed him very greatly. According to the list of names eighteen, not seventeen, members were elected; but apparently only seventeen took part in the proceedings.]

These weather-beaten backwoods warriors, who held their deliberations in the open air, showed that they had in them good stuff out of which to build a free government. They were men of genuine force of character, and they behaved with a dignity and wisdom that would have well become any legislative body. Henderson, on behalf of the proprietors of Transylvania, addressed them, much as a crown governor would have done. The portion of his address dealing with the destruction of game is worth noting. Buffalo, elk, and deer had abounded immediately round Boonesboro when the settlers first arrived, but the slaughter had been so great that even after the first six weeks the hunters began to find some difficulty in getting any thing without going off some fifteen or twenty miles. However, stray buffaloes were still killed near the fort once or twice a week.[4] Calk in his journal quoted above, in the midst of entries about his domestic work — such as, on April 29th “we git our house kivered with bark and move our things into it at Night and Begin housekeeping,” and on May 2d, “went and sot in to clearing for corn,” — mentions occasionally killing deer and turkey; and once, while looking for a strayed mare, he saw four “bofelos.” He wounded one, but failed to get it, with the luck that generally attended backwoods hunters when they for the first time tried their small-bore rifles against these huge, shaggy-maned wild cattle.

[4: Henderson’s Journal.]

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.