What Dragging Canoe said was true, and the whites were taught by years of long warfare that Kentucky was indeed what the Cherokees called it, a dark and bloody ground.

Continuing Daniel Boone Settles Kentucky,

our selection from The Winning of the West, Vol. 1 by Theodore Roosevelt published in 1889. The selection is presented in seven easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Daniel Boone Settles Kentucky.

Time: 1775

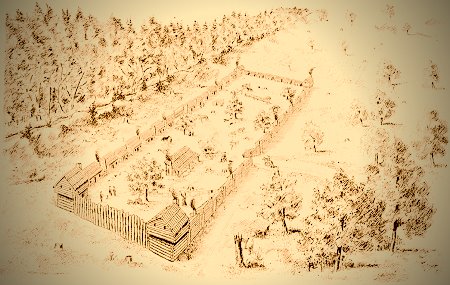

Place: Boonesboro, Kentucky

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

The Indian delegate made a favorable report in January, 1775; and then the Overhill Cherokees were bidden to assemble at the Sycamore Shoals of the Watauga. The order was issued by the head-chief, Oconostota, a very old man, renowned for the prowess he had shown in former years when warring against the English. On the 17th of March, Oconostota and two other chiefs, the Raven and the Carpenter, signed the Treaty of the Sycamore Shoals, in the presence and with the assent of some twelve hundred of their tribe, half of them warriors; for all who could had come to the treaty grounds. Henderson thus obtained a grant of all the lands lying along and between the Kentucky and the Cumberland rivers. He promptly named the new colony Transylvania. The purchase money was 10,000 pounds of lawful English money; but, of course, the payment was made mainly in merchandise, and not specie. It took a number of days before the treaty was finally concluded; no rum was allowed to be sold, and there was little drunkenness, but herds of beeves were driven in, that the Indians might make a feast.

The main opposition to the treaty was made by a chief named Dragging Canoe, who continued for years to be the most inveterate foe of the white race to be found among the Cherokees. On the second day of the talk he spoke strongly against granting the Americans what they asked, pointing out, in words of glowing eloquence, how the Cherokees, who had once owned the land down to the sea, had been steadily driven back by the whites until they had reached the mountains, and warning his comrades that they must now put a stop at all hazards to further encroachments, under penalty of seeing the loss of their last hunting-grounds, by which alone their children could live. When he had finished his speech he abruptly left the ring of speakers, and the council broke up in confusion. The Indian onlookers were much impressed by what he said; and for some hours the whites were in dismay lest all further negotiations should prove fruitless. It was proposed to get the deed privately; but to this the treaty-makers would not consent, answering that they cared nothing for the treaty unless it was concluded in open council, with the full assent of all the Indians. By much exertion Dragging Canoe was finally persuaded to come back; the council was resumed next day, and finally the grant was made without further opposition. The Indians chose their own interpreter; and the treaty was read aloud and translated, sentence by sentence, before it was signed, on the fourth day of the formal talking.

The chiefs undoubtedly knew that they could transfer only a very imperfect title to the land they thus deeded away. Both Oconostota and Dragging Canoe told the white treaty-makers that the land beyond the mountains, whither they were going, was a “dark ground,” a “bloody ground”; and warned them that they must go at their own risk, and not hold the Cherokees responsible, for the latter could no longer hold them by the hand. Dragging Canoe especially told Henderson that there was a black cloud hanging over the land, for it lay in the path of the northwestern Indians — who were already at war with the Cherokees, and would surely show as little mercy to the white men as to the red. Another old chief said to Boone: “Brother, we have given you a fine land, but I believe you will have much trouble in settling it.” What he said was true, and the whites were taught by years of long warfare that Kentucky was indeed what the Cherokees called it, a dark and bloody ground.

[The whole account of this treaty is taken from the Jefferson MSS., 5th Series, Vol. VIII.; “a copy of the proceedings of the Virginia Convention, from June 15 to November 19, 1777, in relation to the Memorial of Richard Henderson, and others”; especially from the depositions of James Robertson, Isaac Shelby, Charles Robertson, Nathaniel Gist, and Thomas Price, who were all present. There is much interesting matter aside from the treaty; Simon Girty makes depositions as to Braddock’s defeat and Bouquet’s fight; Lewis, Croghan, and others show the utter vagueness and conflict of the Indian titles to Kentucky, etc., etc. Though the Cherokees spoke of the land as a “dark” or “bloody” place or ground, it does not seem that by either of these terms they referred to the actual meaning of the name Kentucky. One or two of the witnesses tried to make out that the treaty was unfairly made; but the bulk of the evidence is overwhelmingly the other way. Haywood gives a long speech made by Oconostota against the treaty; but this original report shows that Oconostota favored the treaty from the outset, and that it was Dragging Canoe who spoke against it. Haywood wrote fifty years after the event, and gathered many of his facts from tradition; probably tradition had become confused, and reversed the position of the two chiefs. Haywood purports to give almost the exact language Oconostota used; but when he is in error even as to who made the speech, he is exceedingly unlikely to be correct in anything more than its general tenor.]

After Henderson’s main treaty was concluded, the Watauga Association entered into another, by which they secured from the Cherokees, for 2,000 pounds sterling, the lands they had already leased.

As soon as it became evident that the Indians would consent to the treaty, Henderson sent Boone ahead with a company of thirty men to clear a trail from the Holston to the Kentucky.* This, the first regular path opened into the wilderness, was long called Boone’s trace, and became forever famous in Kentucky history as the Wilderness Road, the track along which so many tens of thousands travelled while journeying to their hoped-for homes in the bountiful west. Boon started on March 10th with his sturdy band of rifle-bearing axemen, and chopped out a narrow bridle-path — a pony trail, as it would now be called in the west. It led over Cumberland Gap, and crossed Cumberland, Laurel, and Rockcastle rivers at fords that were swimming deep in the time of freshets. Where it went through tall, open timber, it was marked by blazes on the tree trunks, while a regular path was cut and trodden out through the thickets of underbrush and the dense canebrakes and reed-beds.

[* Then sometimes called the Louisa; a name given it at first by the English explorers, but by great good-fortune not retained.]

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.