Today’s installment concludes Britain Prepares for World War I,

our selection from The World Crisis, Vol. 1 by Winston S. Churchill published in 1923.

If you have journeyed through all of the installments of this series, just one more to go and you will have completed a selection from the great works of seven thousand words. Congratulations! For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Britain Prepares for World War I.

Time: July 24-30, 1914

Place: Cabinet Room, 10 Downing Street, London

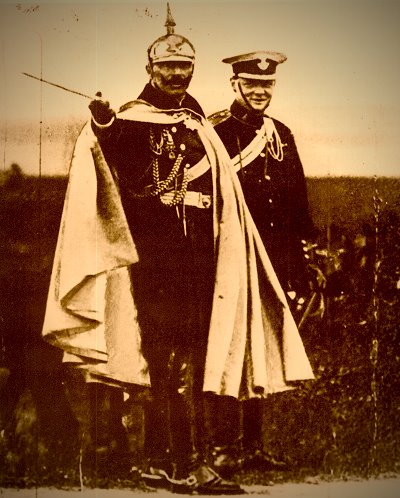

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

The German Naval Attaché thus showed himself extremely well informed. As I have already mentioned in an earlier chapter, the general warrants to open the letters of certain persons which I had signed three years before as Home Secretary, had brought to light a regular network of minor agents, mostly British, in German pay in all our naval ports. Had we arrested them, others of whom we might not have known, would have taken their place. We therefore thought it better, having detected them, to leave them at large. In this way one saw regularly from their communications, which we carefully forwarded, what they were saying to their paymasters in Berlin during these years, and we knew exactly how to put our hands upon them at the proper moment. Up to this point we had no objection to the German Government knowing that exceptional precautions were being taken throughout the Navy. Indeed, apart from details, it was desirable that they should know how seriously we viewed the situation. But the moment had now come to draw down the curtain. We no longer forwarded the letters and a few days later, on a word from me to the Home Secretary, all these petty traitors, who for a few pounds a month were seeking to sell their country, were laid by the heels. Nor was it easy for the Germans to organize on the spur of the moment others in their places.

The most important step remains to be recounted. As early as Tuesday, July 28, I felt that the Fleet should go to its War Station. It must go there at once, and secretly; it must be steaming to the north while every German authority, naval or military, had the greatest possible interest in avoiding a collision with us. If it went thus early it need not go by the Irish Channel and north-about. It could go through the Straits of Dover and through the North Sea, and therefore the island would not be uncovered even for a single day. Moreover, it would arrive sooner and with less expenditure of fuel.

At about 10 o’clock, therefore, on the Tuesday morning I proposed this step to the First Sea Lord and the Chief of the Staff and found them whole-heartedly in favor of it. We decided that the Fleet should leave Portland at such an hour on the morning of the 29th as to pass the Straits of Dover during the hours of darkness, that it should traverse these waters at high speed and without lights, and with the utmost precaution proceed to Scapa Flow. I feared to bring this matter before the Cabinet, lest it should mistakenly be considered a provocative action likely to damage the chances of peace. It would be unusual to bring movements of the British Fleet in Home Waters from one British port to another before the Cabinet. I only therefore informed the Prime Minister, who at once gave his approval. Orders were accordingly sent to Sir George Callaghan, who was told incidentally to send the Fleet up under his second-in-command and to travel himself by land through London in order that we might have an opportunity of consultation with him.

Admiralty to Commander-in-Chief Home Fleets.

July 28, 1914. Sent 5 p.m.

Tomorrow, Wednesday, the First Fleet is to leave Portland for Scapa Flow. Destination is to be kept secret except to flag and commanding officers. As you are required at the Admiralty, Vice-Admiral 2nd Battle Squadron is to take command. Course from Portland is to be shaped to southward, then a middle Channel course to the Straits of Dover. The Squadrons are to pass through the Straits without lights during the night and to pass outside the shoals on their way north. Agamemnon is to remain at Portland, where the Second Fleet will assemble.

We may now picture this great Fleet, with its flotillas and cruisers, steaming slowly out of Portland Harbor, squadron by squadron, scores of gigantic castles of steel wending their way across the misty, shining sea, like giants bowed in anxious thought. We may picture them again as darkness fell, eighteen miles of warships running at high speed and in absolute blackness through the narrow Straits, bearing with them into the broad waters of the North the safeguard of considerable affairs.

Although there seemed to be no conceivable motive, chance or mischance, which could lead a rational German Admiralty to lay a trap of submarines or mines or have given them the knowledge and the time to do so, we looked at each other with much satisfaction when on Thursday morning (the 30th) at our daily Staff Meeting the Flagship reported herself and the whole Fleet well out in the center of the North Sea. 4 The German Ambassador lost no time in complaining of the movement of the Fleet to the Foreign Office. According to the German Official Naval History, he reported to his Government on the evening of the 30th that Sir Edward Grey had answered him in the following words:

‘The movements of the Fleet are free of all offensive character, and the Fleet will not approach German waters.’

‘But,’ adds the German historian, ‘the strategic concentration of the Fleet had actually been accomplished with its transfer to Scottish ports.’ This was true. We were now in a position, whatever happened, to control events, and it was not easy to see how this advantage could be taken from us. A surprise torpedo attack before or simultaneous with the declaration of war was at any rate one nightmare gone forever. We could at least see for ten days ahead. If war should come no one would know where to look for the British Fleet. Somewhere in that enormous waste of waters to the north of our islands, cruising now this way, now that, shrouded in storms and mists, dwelt this mighty organization. Yet from the Admiralty building we could speak to them at any moment if need arose. The king’s ships were at sea.

| <—Previous | Master List |

This ends our series of passages on Britain Prepares for World War I by Winston S. Churchill from his book The World Crisis, Vol. 1 published in 1923. This blog features short and lengthy pieces on all aspects of our shared past. Here are selections from the great historians who may be forgotten (and whose work have fallen into public domain) as well as links to the most up-to-date developments in the field of history and of course, original material from yours truly, Jack Le Moine. – A little bit of everything historical is here.

More information on Britain Prepares for World War I here and here and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.