We were different: we were not used to receiving lessons from others.

Continuing China Awakens 1905,

with a selection from A Chinese Cambridge Man. This selection is presented in 5.5 easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in China Awakens 1905.

Time: 1905

Place: China

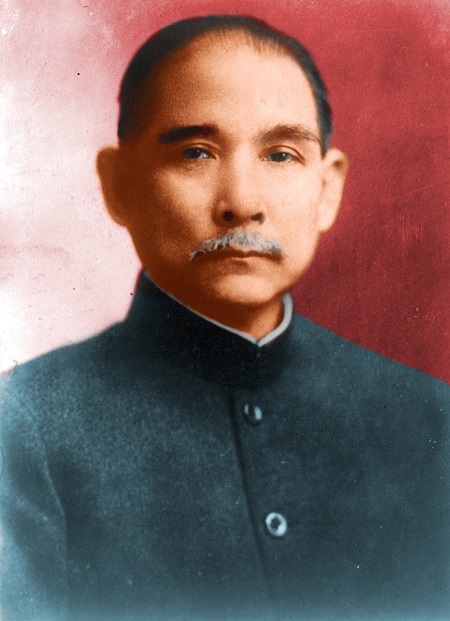

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

But the mass — I mean that of the thinking class — was not so ready to submit prejudice to reason, and therefore the nation as a whole has had to suffer on account of a few. Amour pro pre has been the chief and almost only cause of our pursuing persistently our old course. We could have learned much, but we would not. All the time recognizing that foreigners have much to teach us, and much that we should like to know, we could not for a moment think it possible to stoop to receive instruction from others: we have always been intellectually, if not politically, independent in the East. While secretly admiring, and even longing to possess that which the Europeans knew, we were inventing a thousand and one stories and prejudices to satisfy our own vanity and conceit.

It has, perhaps, never been fully understood by European observers that we were placed on quite a different intellectual standpoint from that of the Japanese. Japan was used to receiving outside influence. Once the Europeans proved to them their superiority, they had no difficulty in adapting themselves to the new state of things, just as they did years ago in adopting Chinese ideas. We were different: we were not used to receiving lessons from others. True it is that Buddhism came to us from India; but then it came mingled with religious enthusiasm, and only acquired its power through centuries of struggle, while its philosophy was almost unknown to us until the ninth century, when under the T’ang Dynasty great freedom of thought was granted. Therefore, cursed with the weakness of overestimating our own qualities, we would not change from a teacher to a pupil.

Never, therefore, was a greater service done to our country than that disastrous war with Japan. China was then really humbled, humbled to an extent she never knew before; for though she was beaten by Europeans over and over again, she was not well prepared, and the engagements were hardly anything like a battle. But not so in the war with Japan: we had a better fleet, which was then considered very efficient by Europeans, and our army, though of less repute, was well armed at least; and besides, the Japanese army was then very insignificant. Yet we were beaten! Before the war we thought that the whole power of Europe was built on cannon, battleships, and machines; so we hastened to buy and even to manufacture these things, imagining that we had nothing more to learn from the West. At least, so thought most of the great men in China then, among whom Li Hung Chang stood prominent. Had we been winners in the war, our conceit would have been immeasurably increased, and there would have been no hope of our ever inquiring into the Western life, still less of appreciating its value. Happily for us, we lost, and the loss opened our eyes. They were so unmistakably opened that even the sternest of reactionaries could not fail to notice that it was something more than mere machines which made the West so powerful, and that we must pay some attention to this or else forfeit our country.

Of late, Europe has been startled by the news that the Chinese Government has taken great steps toward a change. It has reorganized the army, established schools and colleges, sent students abroad, abolished the useless State examinations, founded new boards and offices, and even gone so far as to send a Commission abroad to study the constitutions of the Powers. A parliament has been talked of, opium has been prohibited, and a hundred other things have been done: all these events, either truly or with exaggeration, have been received with great attention in Europe.

Our friends here seem to think that we Orientals can perform miracles; that we can achieve in a few months what Europe has only achieved after years of struggle and blood shed; and that our Government will be so disinterested and generous as to give the people entire freedom at the expense of its own advantages and class privileges. Surely, a little knowledge of history will enable them to see that the road to progress, in its very nature, cannot be shortened even by the length of a step. The Chinese are, after all, but flesh and blood, and cannot, therefore, be excepted from those laws which have been proved over and over again in European history. Governments are conservative by nature, and especially such a one as ours. Every national movement is originated by the ” knowing” people of the nation, and forced upon its Government after it has been well spread among the masses. All the pretenses which the Chinese Government has made lately can be traced to the people. These pretenses were intended not so much to throw dust into the eyes of the foreigners as to quiet the discontent which had been manifesting itself throughout the country. The revolutionary movement was too strong for the weak Government, and our rulers saw that if they rested inactive the opposite movement would be irresistible; and that by grasping too much they would lose their privileges altogether. All their promises were aimed at giving the moderate element among the agitating crowd a hope of obtaining liberty without violence. I do not mean, however, that anything hitherto done by the Chinese Government has had no salutary effects. On the contrary, the abolition of gross abuses has helped us toward real freedom, although the Government did not fore see the consequence.

Enough has been said, I think, to guard us against attaching too much importance to the actions of the Government. The real salvation of China lies with her people, not her Government, and to look for it we must pay more attention to their social movements, which are, after all, the chief fac tors in any political change. I will, therefore, endeavor to show, to the best of my ability, the important changes in social organization, customs, and sentiments in China during the last ten years.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Wu Ting Fang begins here. Adachi Kinnosuke begins here. A Chinese Cambridge Man begins here.

More information here and here.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

In my view, if all web owners and bloggers made just right

content as you did, the web might be a lot more useful than ever before. https://www.construct-solutions.ca

Good day very cool blog!! Man .. Excellent .. Amazing ..

I will bookmark your blog and take the feeds additionally…I’m glad to find numerous useful information here in the post, we need develop

more strategies in this regard, thank you for sharing.

Hey very interesting blog!