The world is accustomed to call us industrious and diligent, but there exists in China a most idle and good-for-nothing class of people.

Continuing China Awakens 1905,

with a selection from A Chinese Cambridge Man. This selection is presented in 5.5 easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in China Awakens 1905.

Time: 1905

Place: China

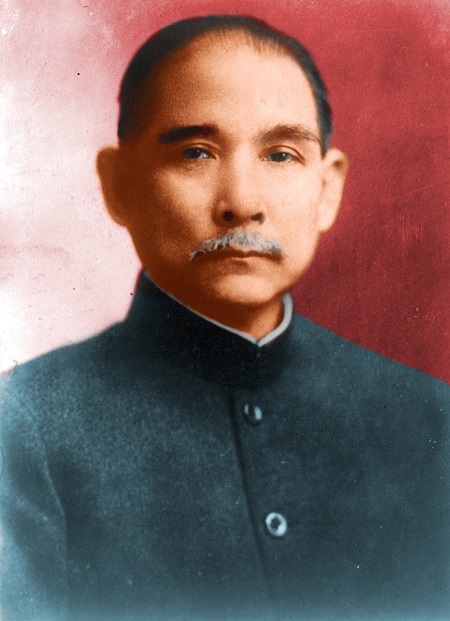

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

Again, there is a great difference between the subjects learned under the old and the new systems. The old state examinations consisted of an artificial system of literature which enslaved the students into drudgery and retarded the formation of true prose. The so-called educated class knew nothing beyond elementary Chinese history and literature, and the world outside was a dead letter to them. To-day in the schools (private or public) elementary sciences are taught and one foreign language at least is compulsory. Geography, history, and literature are methodically if not intelligently taught, and the general ignorance of things has entirely disappeared. In many schools sports and drill are considered essential, and the customary defect in the student’s physique has now vanished.

Last, but not least, the parents’ purpose in sending their children to school is very different from what it was. We have never understood what real education meant. We learned to write and read simply because the state examinations demanded it. Indeed, a child was not allowed by most parents to learn anything but reading and writing. I remember well that ten years ago I was severely handled for trying to make figures on paper. My mother was so frightened that she ordered everything that could possibly attract my attention to this subject to be removed. Therefore those who were not ambitious did not need to go very far, and they did not go far. A merchant or a shopkeeper could hardly write a commercial letter, because to keep the books was all that his situation required. To teach an apprentice anything more than arithmetic and bookkeeping was then horribly ridiculous. The idea of educating a man morally, physically, and intellectually to make him a good citizen never entered our heads. Learning was only regarded as an indispensable means of going into official life, and was therefore totally confined to this class. To-day we send our sons to school mainly for the sake of education. Whatever calling in life they may choose, they must know something more than what their profession demands. If they do their work well they have every hope of being sent abroad to be further educated at the expense of their school, and failing to achieve this, it will not be too late for them to enter on a commercial or other such life that suits them.

Next in importance to the development of the Press and education is the growth of a new system of industry. The world is accustomed to call us industrious and diligent, but there exists in China a most idle and good-for-nothing class of people. I refer to the aristocracy of the country. Being sons of officials or ex-officials, or their relations, any sort of activity is a disgrace to them. Thinking, no doubt, like Benjamin Franklin’s servant, that “the only gentleman in the world is a pig,” they went so far as to grow long nails and wear long robes in order to show how incapable and unfitted they were for work.

On the other hand, the station of the merchant is very low. When he is poor, he is little better than an agricultural laborer. When he is rich, he is liable to be insulted, robbed, or blackmailed by the official class, and this is the chief reason why the Chinese emigrants in America are afraid to come home after having made their fortunes. By degrees, however, their importance is being felt, and the proud aristocracy are beginning to feel uneasy. They may still retain their dignity, they may make their importance felt, they may rest idle all day long, but they can not live half so comfortably as those merchants whom they despise. To enter into the state service is not an easy matter, for the supply far exceeds the demand: the misery of those waiting for appointments is proverbial. They now look around and begin to think whether it is not a mistake to let others make money and themselves to starve. The Press is daily urging the importance of exploring mineral wealth, building factories, and creating new industries. The few of their class who have had the opportunity of traveling represent to them pleasant pictures of the corresponding class in other countries, where every man tries to do his share. All these forces combine to direct their attention to an active life; and, to do them justice, quite a number of them have begun devoting themselves to some occupation. The following serves for an illustration:

Chang Gien, a native of T’ung-chow, being a Chong Yuan (the Senior Wrangler in the examination for the Hanlin or third degree), was entitled to some great Government post, but instead he returned to his native province and there erected a cotton factory. This caused a great scandal in the whole province, and his relations were astonished and dis gusted. The affair was the chief topic of talk and gossip for months in the neighboring towns and everybody condemned him as being mad and unbecoming his high dignity. But in spite of all he went on with his work quietly, and with sufficient capital he introduced the most up-to-date system of manufacturing cotton goods. After nine years of hard labor he now employs 2,500 hands, and realized in 1905 a net profit of £50,000 sterling. T’ung-chow, which ranked among the poorest towns in the province, is now one of the chief industrial centers, and will soon be opened to foreign commerce, not as a “treaty port,” but as a free market. Mr. Chang is now the most influential man in the province, and nobody attempts any enterprise without first obtaining his advice. He is the president of a railway company, of the Association of Printers and Publishers, and of the Chamber of Commerce, all of which are of recent formation. Once the spell is broken, every man is following his example, and what a blessing this is to us! A modern industry cannot flourish if the prospects are not secure, and the security of an enterprise is diminished in inverse ratio to its importance in a country where blackmail and official interference are so frequent. An enterprise under taken by a member of the aristocracy is therefore the only one that can stand firm: even a viceroy risks his position by daring to interfere with it. The ex- Viceroy of Canton lost his place through acting directly against the local gentry.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Wu Ting Fang begins here. Adachi Kinnosuke begins here. A Chinese Cambridge Man begins here.

More information here and here.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.