On Saturday afternoon the news came in that Serbia had accepted the ultimatum. I went to bed with a feeling things might blow over.

Continuing Britain Prepares for World War I,

our selection from The World Crisis, Vol. 1 by Winston S. Churchill published in 1923. The selection is presented in seven easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Britain Prepares for World War I.

Time: July 24-30, 1914

Place: Cabinet Room, 10 Downing Street, London

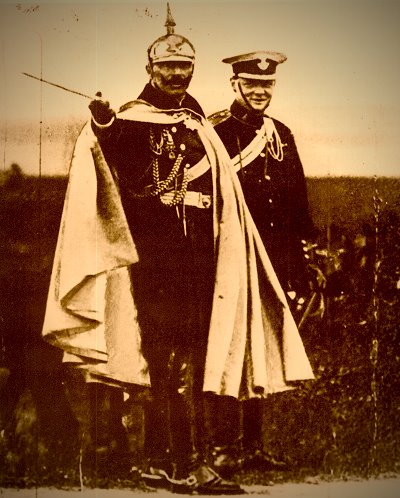

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

It all depended on the Tsar. What would he do if Austria chastised Serbia? A few years before there would have been no danger, as the Tsar was too frightened for his throne, but now again he was feeling himself more secure upon his throne, and the Russian people besides would feel very hardly anything done against Serbia. Then he said, ‘If Russia marches against Austria, we must march; and if we march, France must march, and what would England do?’ I was not in a position to say more than that it would be a great mistake to assume that England would necessarily do nothing, and I added that she would judge events as they arose. He replied, speaking with very great earnestness. ‘Suppose we had to go to war with Russia and France, and suppose we defeated France and yet took nothing from her in Europe, not an inch of her territory, only some colonies to indemnify us. Would that make a difference to England’s attitude? Suppose we gave a guarantee beforehand.’ I stuck to my formula that England would judge events as they arose, and that it would be a mistake to assume that we should stand out of it whatever happened.

I reported this conversation to Sir Edward Grey in due course, and early in the following week I repeated it to the Cabinet. On the Wednesday following the exact proposal mooted to me by Herr Ballin, about Germany not taking any territorial conquests in France but seeking indemnities only in the colonies, was officially telegraphed to us from Berlin and immediately rejected. I have no doubt that Herr Ballin was directly charged by the Emperor with the mission to find out what England would do.

Herr Ballin has left on record his impression of his visit to England at this juncture. ‘Even a moderately skilled German diplomatist,’ he wrote, ‘could easily have come to an understanding with England and France, who could have made peace certain and prevented Russia from beginning war.’ The editor of his memoirs adds: ‘The people in London were certainly seriously concerned at-the Austrian Note, but the extent to which the Cabinet desired the maintenance of peace may be seen (as an example) from the remark which Churchill, almost with tears in his eyes, made to Ballin as they parted: “My dear friend, don’t let us go to war.”

I had planned to spend the Sunday with my family at Cromer, and I decided not to alter my plans. I arranged to have a special operator placed in the telegraph office so as to ensure a continuous night and day service. On Saturday afternoon the news came in that Serbia had accepted the ultimatum. I went to bed with a feeling things might blow over. We had had, as this account has shown, so many scares before. Time after time the clouds had loomed up vague, menacing, constantly changing; time after time they had dispersed. We were still a long way, as it seemed, from any danger of war. Serbia had accepted the ultimatum, could Austria demand more? And if war came, could it not be confined to the East of Europe? Could not France and Germany, for instance, stand aside and leave Russia and Austria to settle their quarrel? And then, one step further removed, was our own case. Clearly there would be a chance of a conference, there would be time for Sir Edward Grey to get to work with conciliatory processes such as had proved so effective in the Balkan difficulties the year before. Anyhow, whatever happened, the British Navy had never been in a better condition or in greater strength. Probably the call would not come, but if it did, it could not come in a better hour. Reassured by these reflections I slept peacefully, and no summons disturbed the silence of the night.

At 9 o’clock the next morning I called up the First Sea Lord by telephone. He told me that there was a rumor that Austria was not satisfied with the Serbian acceptance of the ultimatum, but otherwise there were no new developments. I asked him to call me up againat twelve. I went down to the beach and played with the children. We dammed the little rivulets which trickled down to the sea as the tide went out. It was a very beautiful day. The North Sea shone and sparkled to a far horizon. What was there beyond that line where sea and sky melted into one another? All along the East Coast, from Cromarty to Dover, in their various sally-ports, lay our patrol flotillas of destroyers and submarines. In the Channel behind the torpedo-proof moles of Portland Harbor waited all the great ships of the British Navy. Away to the north-east, across the sea that stretched before me, the German High Sea Fleet, squadron by, squadron, was cruising off the Norwegian coast.

At 12 o’clock I spoke to the First Sea Lord again. He told me various items of news that had come in from different capitals, none however of decisive importance, but all tending to a rise of temperature. I asked him whether all the reservists had already been dismissed. He told me they had. I decided to return to London. I told him I would be with him at nine, and that meanwhile he should do whatever was necessary.

Prince Louis awaited me at the Admiralty. The situation was evidently degenerating. Special editions of the Sunday papers showed intense excitement in nearly every European capital. The First Sea Lord told me that in accordance with our conversation he had told the Fleet not to disperse. I took occasion to refer to this four months later in my letter accepting his resignation. I was very glad publicly to testify at that moment of great grief and pain for him that his loyal hand had sent the first order which began our vast naval mobilization. I then went round to Sir Edward Grey, who had rented my house at 33 Eccleston Square. No one was with him except Sir William Tyrrell of the Foreign Office. I told him that we were holding the Fleet together. I learned from him that he viewed the situation very gravely. He said there was a great deal yet to be done before a Really dangerous crisis was reached, but that he did not at all like the way in which this business had begun. I asked whether it would be helpful or the reverse if we stated in public that we were keeping the Fleet together. Both he and Tyrrell were most insistent that we should proclaim it at the earliest possible moment: it might have the effect of sobering the Central Powers and steadying Europe. I went back to the Admiralty, sent for the First Sea Lord, and drafted the necessary communiqué.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.