The Cabinet was overwhelmingly pacific. At least three-quarters of its members were determined not to be drawn into a European quarrel.

Continuing Britain Prepares for World War I,

our selection from The World Crisis, Vol. 1 by Winston S. Churchill published in 1923. The selection is presented in seven easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Britain Prepares for World War I.

Time: July 24-30, 1914

Place: Cabinet Room, 10 Downing Street, London

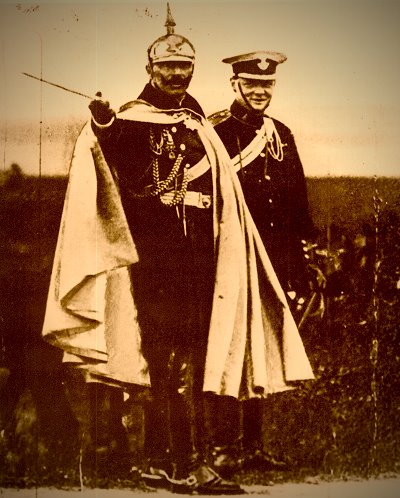

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

The next morning the following notice appeared in all the papers:

BRITISH NAVAL MEASURES

ORDERS TO FIRST AND SECOND FLEETS

NO MANOEVRE LEAVE

We received the following statement from the Secretary of the Admiralty at an early hour this morning:

Orders have been given to the First Fleet, which is concentrated at Portland, not to disperse for maneuver leave for the present. All vessels of the Second Fleet are remaining at their home ports in proximity to their balance crews.

On Monday began the first of the Cabinets on the European situation, which thereafter continued daily or twice a day. It is to be hoped that sooner or later a detailed account of the movement of opinion in the Cabinet during this period will be compiled and given to the world. There is certainly no reason for anyone to be ashamed of honest and sincere counsel given either to preserve peace or to enter upon a just and necessary war. Meanwhile it is only possible, without breach of constitutional propriety, to deal in the most general terms with what took place.

The Cabinet was overwhelmingly pacific. At least three-quarters of its members were determined not to be drawn into a European quarrel, unless Great Britain were herself attacked, which was not likely. Those who were in this mood were inclined to believe first of all that Austria and Serbia would not come to blows; secondly, that if they did, Russia would not intervene; thirdly, if Russia intervened, that Germany would not strike; fourthly, they hoped that if Germany struck at Russia, it ought to be possible for France and Germany mutually to neutralize each other without fighting. They did not believe that if Germany attacked France, she would attack her through Belgium or that if she did the Belgians would forcibly resist; and it must be remembered, that during the whole course of this week Belgium not only never asked for assistance from the guaranteeing Powers but pointedly indicated that she wished to be left alone. So here were six or seven positions, all of which could be wrangled over and about none of which any final proof could be offered except the proof of events. It was not until Monday, August 3, that the direct appeal from the King of the Belgians for French and British aid raised an issue which united the overwhelming majority of Ministers and enabled Sir Edward Grey to make his speech on that afternoon to the House of Commons.

My own part in these events was a very simple one. It was first of all to make sure that the diplomatic situation did not get ahead of the naval situation, and that the Grand Fleet should be in its War Station before Germany could know whether or not we should be in the war, and therefore if possible before we had decided ourselves. Secondly, it was to point out that if Germany attacked France, she would do so through Belgium, that all her preparations had been made to this end, and that she neither could nor would adopt any different strategy or go round any other way. To these two tasks I steadfastly adhered.

Every day there were long Cabinets from eleven onwards. Streams of telegrams poured in from every capital in Europe. Sir Edward Grey was plunged in his immense double struggle (a) to prevent war and (b) not to desert France should it come. I watched with admiration his activities at the Foreign Office and cool skill in Council. Both these tasks acted and reacted on one another from hour to hour. He had to try to make the Germans realize that we were to be reckoned with, without making the French or Russians feel they had us in their pockets. He had to carry the Cabinet with him in all he did. During the many years we acted together in the Cabinet, and the earlier years in which I read his Foreign Office telegrams, I thought I had learnt to understand his methods of discussion and controversy, and perhaps without offence I might describe them.

After what must have been profound reflection and study, the Foreign Secretary was accustomed to select one or two points in any important controversy which he defended with all his resources and tenacity. They were his fortified villages. All around in the open field the battle ebbed and flowed, but if at nightfall these points were still in his possession, his battle was won. All other arguments had expended themselves, and these key positions alone survived. The points which he selected over and over again proved to be inexpugnable. They were particularly adapted to defense. They commended themselves to sensible and fair-minded men. The sentiments of the patriotic Whig, the English gentleman, the public school boy all came into the line for their defense, and if they were held, the whole front was held, including much debatable ground.

As soon as the crisis had begun he had fastened upon the plan of a European conference, and to this end every conceivable endeavor was made by him. To get the Great Powers together round a table in any capital that was agreeable, with Britain there to struggle for peace, and if necessary to threaten war against those who broke it, was his plan. Had such a conference taken place, there could have been no war. Mere acceptance of the principle of a conference by the Central Powers would have instantly relieved the tension. A will to peace at Berlin and Vienna would have found no difficulties in escaping from the terrible net which was drawing in upon us all hour by hour. But underneath the diplomatic communications and maneuvers, the baffling proposals and counter-proposals, the agitated interventions of Tsar and Kaiser, flowed a deep tide of calculated military purpose. As the ill fated nations approached the verge, the sinister machines of war began to develop their own momentum and eventually to take control themselves.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.