The effects of this great change for the better in the Press are innumerable and somewhat difficult to analyze.

Continuing China Awakens 1905,

with a selection from A Chinese Cambridge Man. This selection is presented in 5.5 easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in China Awakens 1905.

Time: 1905

Place: China

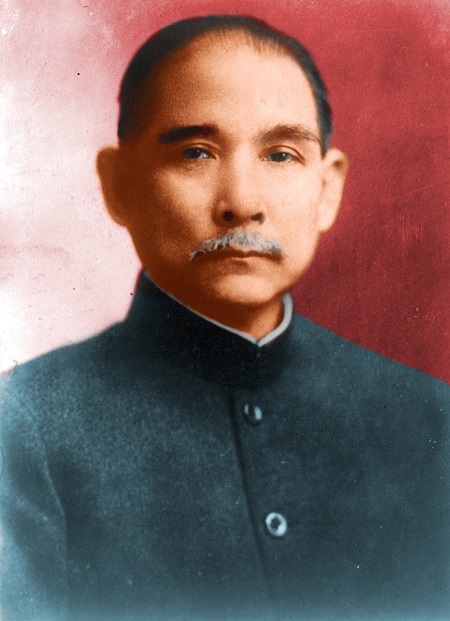

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

First and foremost among these changes came the development of the Press. True it is that there has always been a sort of official newspaper published in Peking; but it was miserably printed and contained nothing but edicts and official appointments. In some respects it resembled the London Gazette of the seventeenth century. There was no article and no discussion of any kind. No one, except those who were expecting appointments, ever dreamed of reading it. Before the Chino- Japanese War two daily papers were published in Shanghai: the Sin-pao and the Sin-min-chung-pao. They had some resemblance to a newspaper, but they were badly written and worse printed. There was a weak and timorous leading article — the editor dared not say anything beyond what was metaphorical — and the news was more or less local and hardly worth reading. Their readers were consequently very few. In my native town, where there were sixty thou sand people (out of whom at least three thousand could read), only one copy of the Sin-pao was to be found. The privileged reader of this solitary copy was, of course, an exceptionally well-read man. I remember well, when the war with Japan was going on, how people used to flock to his residence for news, and how they expressed their indignation and disbelief when a defeat on our side was announced. The paper was sent to him weekly, and often arrived at its destination after a delay of three or four weeks, although we were within a night’s journey of Shanghai, where it was published. The fact is, there was not a single Government post-office in my town then, and the papers were delivered by a merchant’s agent, who not only read them first, but circulated them among his friends and relations before finally putting them into the hands of the original subscriber. To-day, what a contrast! In the same town two hundred copies of the above-mentioned paper are sold, besides many other journals.

The number of newspapers has increased with amazing rapidity within the last decade. In Peking, where no news papers existed before 1902, there are now ten; and — most surprising of all — one of these is edited by a woman. In all the large provincial towns — even in such a one as Tai-yuan-f 00 in Shan-se, which is situated so far from the coast that until recently the difficulty of communication has been extreme — local papers are published. It is at Shanghai, however, that these palpitators of public opinion abound. Under the protection of the settlement, they are free from interference by the officials, and, taking this advantage, the editor’s attitude has become easy and bold. The result of this is that not only is the increase in numbers great, but the improvements which some of these papers have undergone within a short period is amazing. Take, for example, the Chong-wai-tse-pao (the Universal Gazette), which was founded about 1898, under a management that was shocking in the extreme. Five years ago it had only four pages, but now it has twelve. It has special correspondents all over China, and all the news is sent by wire. Important news is printed in large type and neatly arranged in order of the provinces. The leading articles are very out spoken and bold. They are probably of very little literary value, but this is arranged expressly for the purpose of widening its circulation among the less-educated classes. Foreign news is not neglected. Though it has no special correspondents in Europe, it has one in Japan, and voluntary contributions from our students in Europe (which are plentiful) are eagerly sought after and carefully chosen.

No less well-organized is the Tse-pao (the Eastern Times). In fact, as far as internal politics are concerned, no newspapers in Europe or in Japan are so well informed. Its managers spare neither pains nor expense to “fish out” those secrets which the Government wishes to keep, and their achievements toward this end are a continuous history of remarkable “scoops.” Long before the New Tibetan Treaty was signed every article in it was published and analyzed. The details of the administrative reform of last September and the appointment of the new Viceroy of Manchuria appeared two clear months before the edicts were out. Then, besides politics, many interesting topics are discussed. Serial and short stories are published: some of them are translations of well-known works in English or French, but more frequently we find in them satires written in a form calculated to expose the rottenness of the existing Government and Legislature.

Parallel with the improvements in newspapers runs the increase in the number of books and periodicals. All sorts of monthly and fortnightly reviews have literally sprung into existence, and new books come out by the score every month, most of them being translations of works on politics, history, philosophy, laws, science, and arts. In the periodicals party spirit sometimes runs very high, and two papers of different parties — for instance, the Min-pao (the People), which is conducted by Dr. Sun Yat Sen, the well-known revolutionary leader, and the Sin-min-chung-pao (the New People), the organ of Mr. K’wang Yu Wei, the great reformer — will often engage in a hot debate over questions of burning importance.

The effects of this great change for the better in the Press are innumerable and somewhat difficult to analyze. Some idea, however, may be derived from the following description. Ten years ago, to take for illustration the facts in my own town as I have done above, there was no such thing as a reading public. This has been created solely by the Press. In those days the publication of a new book was most rare. The books published were reprints of the classics, and in the latter half of the nineteenth century, a few translations of scientific text-books. As with all such books, their circulation was very limited. The majority of those who can read seldom go beyond the popular novels such as: “The History of the Three Kingdoms,” and “The Heroes of the Isle.” Nobody ever troubled himself about politics. During the Chino- Japanese War very few people had any clear idea of the events. We knew, of course, that we were disagreeably beaten, but as to how, why, when, or where we had not the slightest idea. At that time, the Government was nothing to the people. Not one in ten thousand could name the Ministers of State or the Governors and Viceroys of the different provinces, much less discuss their actions and characters. To-day, even a schoolboy can give you a fairly accurate account of the late Russo-Japanese War; and a village teacher, who has probably never been outside his native village, talks with enthusiasm about the coming Constitution, the Educational Policy, the change of the important officials, etc., etc. The influence of the Press, therefore, is immense, and the members of the Government are not slow to realize that they are being handicapped very much in their old tyrannical ways. They are trying every means to get the papers under their own control — but they will never succeed.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Wu Ting Fang begins here. Adachi Kinnosuke begins here. A Chinese Cambridge Man begins here.

More information here and here.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.