Not so many years ago many thoughtful people excused the Peking Government for neglecting to attend to many important governmental functions, because it seemed almost impossible for it to do very much beyond throwing away valuable concessions for railway construction.

Continuing China Awakens 1905,

with a selection from Adachi Kinnosuke. This selection is presented in 2.5 installments, each one 5 minutes long. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in China Awakens 1905.

Time: 1905

Place: China

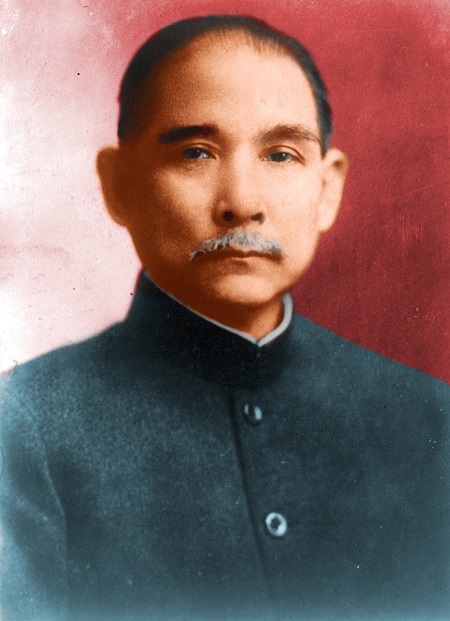

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

Next, there was issued at Peking, on March 15, 1899, an imperial decree by means of which there was conferred upon the Roman Catholic bishops an official rank similar to that of the viceroys and the governors of provinces in China. In this, China did not particularly wish to put into practice the injunction of the Master in whose name those French missionary bishops everlastingly raised so much mischief, namely, “Love your enemies.” But then there were, back of the French demand, the “battalions and cannons” which the Kaiser worships as the guardian gods of peace, and China knew better than to resist.

Finally, the method by means of which the Czar robbed China of something like 3,000,000 square miles, that is to say, of an area about twenty times as large as Japan, is too well known to require discussion.

Not so many years ago many thoughtful people excused the Peking Government for neglecting to attend to many important governmental functions, because it seemed almost impossible for it to do very much beyond throwing away valuable concessions for railway construction. Russia received the East China Railway concession; Germany, that of Kiaochau (343 miles); England, the Tientsin-Shanghai-Kwan (130 miles), the Shanghai-Kwan and Shinmin-tun (240 miles), the Tientsin and Chinkiang (600 miles), and seven others calling for the construction of over two thousand miles of railroad. The French and the Belgians received the Peking- Hankow and five other concessions, while the Americans received the Canton-Hankow concession. With the single exception of the American concession, China gave these valuable things away, not because she wished to do so, but because she could not help herself.

Such, then, was the China of yesterday. Let us now turn our attention to the China of to-day.

On the authority of Sir Chengtung Liancheng, the able and distinguished Chinese Minister to the United States, we have it that the days of concession-giving in China are over. On August 29, 1905, China purchased back from the Americans the Canton-Hankow railroad concession, at a rather fancy price, it is true, but one which was, nevertheless, very low when one looks upon it as the price of the command by China of her own artery.

Today there is no Li-Hung-Chang at Peking, neither is there a Count Cassini seated across the table from him. Nothing is more remarkable than the rise of Chang Chihtung of Nan-p’i, that famous viceroy at Hankow, to the supreme power in the council chamber of the Chinese empire. It was this enlightened Viceroy who wrote, in his famous work, “Chuen Hio Pien,” which he published shortly after the China-Nippon war: “In order to render China powerful, and at the same time preserve our institutions, it is absolutely necessary that we should utilize Western knowledge. But unless Chinese learning be made the basis of education, and a Chinese direction be given to thought, the strong will become anarchists and the weak slaves. Thus the latter end will be worse than the former.”

Happily for China, Chang looks upon education as the salvation of the Chinese empire. He was the pioneer in sending students to Nippon. And Nippon was delighted to receive with the students from Hupeh a grandson of Chang Chihtung, to whom the Nippon Government extended the courtesy of permitting him to enter the Nobles’ College at Tokyo. Vice roys Liu K’unyi and Yu-lu, and the governors of Chekiang and Kiangsi, as well as many others, followed the example of Chang Chihtung. Today over four thousand Chinese students, including both sexes, are to be found in the Nippon colleges and schools.

One day in August, 1904, there was held in Tokyo a meeting attended by a majority of the sixty Chinese girls then carrying on their educational work in the girls’ schools of that city. To see those young ladies of China mounting a public platform was certainly a novel sight. But what they said upon that occasion was still more amazing. In their modest way, they had just formed an association for the purpose of accomplishing something that would have shocked even the most extravagant immodesty of the most ambitious statesman of China. In a word, they had united in order that they might work for the abolition, once for all, of the evil custom called the “golden lily,” which tyrannizes over the women of China with a refinement of cruelty worthy of Nero; which tortures the tender years of their girlhood with an excruciating pain that does not cease even in the hours of sleep; which threatens the freedom of motion in their more mature years; and which totally destroys the grace and form of their feet. But these Chinese girl students did not content themselves with smashing the ancient sense of propriety by thus haranguing a public audience; for the association actually went so far as to print, in pamphlet form, the addresses made by the students, and to send the copies of their speeches home for distribution among the women of China. Such acts as these are certainly a far cry from the action of Chinese women generally, and particularly as the latter are understood by the people of the Western hemisphere.

All over China, schools for girls as well as for boys are springing up to-day; and many Nippon women, graduates of the various normal schools of Japan, have been engaged by the Chinese viceroys to instruct in their schools. For years, Chang Chihtung has looked to popular education as the means of accomplishing the thing of greatest importance to China, namely, the awakening of nationalism in the minds of her people; and education is now beginning to bear the desired fruit. ” The Chinaman has no fatherland, he has a native district. He has no nation, he has a family. He has no state, he has a society. He has no sovereign, he has only Government officials.” So wrote Alexander Ular not many months ago. He should have written it ten years ago.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Wu Ting Fang begins here. Adachi Kinnosuke begins here. A Chinese Cambridge Man begins here.

More information here and here.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.