This series has seven easy 5 minute installments. This first installment: Just as the Meeting Was Ending.

Introduction

What was it like when the news arrived and the realization first came that Great Britain might have to go to war? Winston Churchill takes us inside the Cabinet Room at this moment. Then what did the government do next?

This selection is from The World Crisis, Vol. 1 by Winston S. Churchill published in 1923. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Winston S. Churchill (1874-1965) was the First Lord of the Admiralty (head of the navy) at the beginning of this war. At the end of it he was Secretary of War. In the Second World War he was the Prime Minister. Later he won the Nobel Prize for Literature.

Time: July 24-30, 1914

Place: Cabinet Room, 10 Downing Street, London

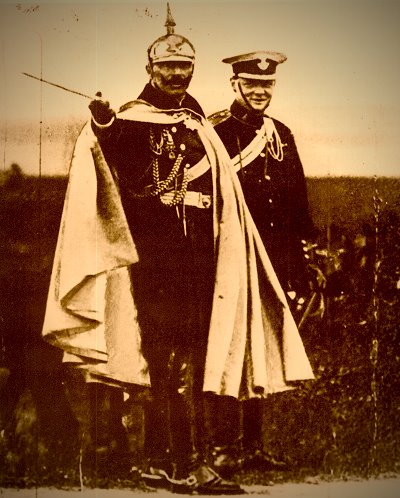

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

The Cabinet on Friday afternoon sat long revolving the Irish problem. The Buckingham Palace Conference had broken down. The disagreements and antagonisms seemed as fierce and as hopeless as ever, yet the margin in dispute, upon which such fateful issues hung, was inconceivably petty. The discussion turned principally upon the boundaries of Fermanagh and Tyrone. To this pass had the Irish factions in their insensate warfare been able to drive their respective British champions. Upon the disposition of these clusters of humble parishes turned at that moment the political future of Great Britain. The North would not agree to this, and the South would not agree to that. Both the leaders wished to settle; both had dragged their followers forward to the utmost point they dared. Neither seemed able to give an inch. Meanwhile, the settlement of Ireland must carry with it an immediate and decisive abatement of party strife in Britain, and those schemes of unity and co-operation which had so intensely appealed to the leading men on both sides, ever since Mr. Lloyd George had mooted them in 1910, must necessarily have come forward into the light of day. Failure to settle on the other hand meant something very like civil war and the plunge into depths of which no one could make any measure. And so, turning this way and that in search of an exit from toe deadlock, the Cabinet toiled around the muddy byways of Fermanagh and Tyrone. One had hoped that the events of April at the Curragh and in Belfast would have shocked British public opinion, and formed a unity sufficient to impose a settlement on the Irish factions. Apparently they had been insufficient. Apparently the conflict would be carried one stage further by both sides with incalculable consequences before there would be a recoil. Since the days of the Blues and the Greens in the Byzantine Empire, partisanship had rarely been carried to more absurd extremes. An all-sufficient shock was, however, at hand.

The discussion had reached its inconclusive end, and the Cabinet was about to separate, when the quiet grave tones of Sir Edward Grey’s voice were heard reading a document which had just been brought to him from the Foreign Office. It was the Austrian note to Serbia. He had been reading or speaking for several minutes before I could disengage my mind from the tedious and bewildering debate which had just closed. We were all very tired, but gradually as the phrases and sentences followed one another, impressions of a wholly different character began to form in my mind. This note was clearly an ultimatum; but it was an ultimatum such as had never been penned in modern times. As the reading proceeded it seemed absolutely impossible that any State in the world could accept it, or that any acceptance, however abject, would satisfy the aggressor. The parishes of Fermanagh and Tyrone faded back into the mists and squalls of Ireland, and a strange light began immediately, but by perceptible gradations, to fall and grow upon the map of Europe. I always take the greatest interest in reading accounts of how the war came upon different people; where they were, and what they were doing, when the first impression broke on their mind, and they first began to feel this overwhelming event laying its fingers on their lives. I never tire of the smallest detail, and I believe that so long as they are true and unstudied they will have a definite value and an enduring interest for posterity; so I shall briefly record exactly what happened to me.

I went back to the Admiralty at about 6 o’clock. I said to my friends who have helped me so many years in my work 1 that there was real danger and that it might be war.

I took stock of the position, and wrote out to focus them in my mind a series of points which would have to be attended to if matters did not mend. My friends kept these as a check during the days that followed and ticked them off one by one as they were settled.

Seventeen Points to Remember

- First and Second Fleets. Leave and disposition.

- Third Fleet. Replenish coal and stores.

- Mediterranean movements.

- China dispositions.

- Shadowing cruisers abroad.

- Ammunition for self-defensive merchantmen.

- Patrol Flotillas.

Disposition. Leave. Complete. 35 ex-Coastals. - Immediate Reserve.

- Old Battleships for Humber. Flotilla for Humber.

- Ships at emergency dates. Ships building for Foreign Powers.

- Coastal Watch.

- Anti-aircraft guns at Oil Depots.

- Aircraft to Sheerness. Airships and Seaplanes.

- K. Espionage.

- Magazines and other vulnerable points.

- Irish ships.

- Submarine dispositions.

I discussed the situation at length the next morning (Saturday) with the First Sea Lord. For the moment, however, there was nothing to do. At no time in all these last three years were we more completely ready.

The test mobilization had been completed, and with the exception of the Immediate Reserve, all the reservists were already paid off and journeying to their homes. But the whole of the 1st and 2nd Fleets were complete in every way for battle and were concentrated at Portland, where they were to remain till Monday morning at 7 o’clock, when the 1st Fleet would disperse by squadrons for various exercises and when the ships of the 2nd Fleet would proceed to their Home Ports to discharge their balance crews. Up till Monday morning therefore, a word instantaneously transmitted from the wireless masts of the Admiralty to the Iron Duke would suffice to keep our main force together. If the word were not spoken before that hour, they would begin to separate. During the first twenty-four hours after their separation they could be re-concentrated in an equal period; but if no word were spoken for forty-eight hours (i.e. by Wednesday morning), then the ships of the 2nd Fleet would have begun dismissing their balance crews to the shore at Portsmouth, Plymouth and Chatham, and the various gunnery and torpedo schools would have recommenced their instruction. If another forty-eight hours had gone before the word was spoken, i.e. by Friday morning, a certain number of vessels would have gone into dock for refit, repairs or laying up. Thus on the Saturday morning we had the Fleet in hand for at least four days. The night before (Friday), at dinner, I had met Herr Ballin. He had just arrived from Germany. We sat next to each other, and I asked him what he thought about the situation. With the first few words he spoke, it became clear that he had not come here on any mission of pleasure. He said the situation was grave. ‘I remember,’ he said, ‘old Bismarck telling me the year before he died that one day the great European War would come out of some damned foolish thing in the Balkans.’ These words, he said, might come true.

| Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.