Today’s installment concludes Mexico Rejects Maximilian,

the name of our combined selection from Charles A. Fyffe and Felix Salm-Salm. The concluding installment, by Felix Salm-Salm from My Diary in Mexico, was published in 1868.

If you have journeyed through all of the installments of this series, just one more to go and you will have completed three thousand words from great works of history. Congratulations! For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Mexico Rejects Maximilian.

Time: 1867

Place: Mexico

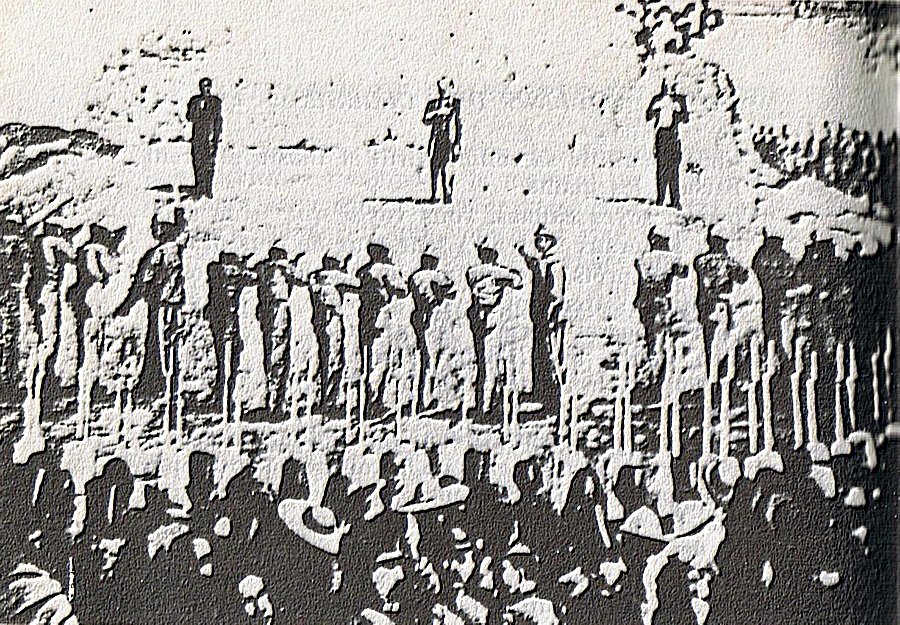

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

In the morning of the 19th, at four o’clock, all were up in our convent, for the disposable part of the battalion Supremos Poderes marched out at half past four. Soon after six o’clock Lieu tenant-Colonel Pitner came into the room adjoining the chapel, and called out, “They have already led him awayl ”

We now listened with breathless anxiety; but nothing be trayed what had happened, when on a sudden all the bells of the city began ringing after seven o’clock. Pitner called out, “He is dead now!” and, not caring for the sentinel at my door, he rushed into the chapel, and in a mute embrace our tears fell in memory of the much beloved, noble dead. Toward eight o’clock the troops returned from the execution.

The last moments of the Emperor have been frequently described; but all these descriptions differ from one another. Though it was not my lot to assist my Emperor in his last moments, I shall write down what eight or ten Liberal officers, among whom was Colonel Villanueva, concurred in saying.

The Emperor rose as early as half past three, and made a very careful toilet. He wore a short dark (blue or black) coat, black trousers and waistcoat, and a small felt hat. At four o’clock Pater Soria came, from whom the Emperor had already received the last sacraments. At five o’clock a mass was celebrated, for which purpose an altar had been placed in a convenient niche. The Emperor gave to Doctor Basch several commissions and greetings to his friends, among whom he did not forget to mention me. He then breakfasted at a quarter to six. The people in the city were much excited, and this excitement was even noticeable among some portion of the troops. Escobedo was afraid of demonstrations, and even of a riot, and to baffle such at tempts the execution was ordered to take place an hour sooner.

With the stroke of six o’clock the Liberal officer came to take the Emperor. Before he had yet spoken, the Emperor said, “I am ready,” and came from his cell, where he was surrounded by his few servants, who wept and kissed his hands. He said: “Be calm; you see I am so. It is the will of God that I should die, and we cannot act against that.”

The Emperor then went toward the cells of his two generals, and said: “Are you ready, gentlemen? I am ready.” Miramon and Mejia came forward, and he embraced his companions in death. Mejia, the brave, daring man, who hundreds of times had looked smilingly into the face of grim Death, was weakened by sickness and very low-spirited. All three went down the staircase, the Emperor in advance with a firm step. On arriving at the street before the convent he looked around, and, drawing a deep breath, he said: “Ah, what a splendid day! I always wished to die on such a day.” He then stepped with Pater Soria into the next carriage waiting for him, the fiacre No. 10; for the republican Government probably thought it below its dignity to provide a proper carriage for a fallen Emperor. Mira mon entered the fiacre No. 16, and Mejia, No. 13, and the mournful procession moved. At its head marched the Supremos Poderes. The carriages were surrounded by the Cazadores de Galeano, and the rear was brought up by the battalion Nueva Leon, which was ordered for the execution.

Though the hour had been anticipated, the streets were crowded. Everybody greeted the Emperor respectfully, and the women cried aloud. The Emperor responded to the greetings with his heart-winning smile, and perhaps compared his present march with his entrance and reception into Queretaro four months ago. What a contrast! However, the people kept quiet, and could not muster courage for any demonstration; only the soldiers were favored with odious names and missiles.

On their arrival at the Cerro de la Campafia, the door of the Emperor’s fiacre could not be opened. Without waiting for further attempts to do so, the Emperor jumped to the ground. At his side stood his Hungarian servant, Tudos. On looking around he asked the servant, “Is nobody else here?” In his fortunate days everybody strove to be near him, but now on the way to his untimely grave only a single person was at his side. However, Baron Magnus and Consul Bahnsen were present, though he could not see them.

Pater Soria dismounted as well as he could. But the comforter required comfort from the condemned. He felt sick and faint, and with a compassionate look the Emperor drew from his pocket a smelling-bottle (which my wife had given him, and which is said to be now in the possession of the widowed Empress of Brazil), and held it under his nose.

The Emperor, followed by Miramon, and Mejia, who had to be supported, now moved toward the square of soldiers, which was open toward the cerro. The troops for the execution were commanded by General Jesus Diaz de Leon. Where the square was open, a wall of adobe had been erected. In the middle, where the Emperor was to stand, who was taller than his two companions, the wall was somewhat higher. On the point of taking their respective positions, the Emperor said to Miramon: “ A brave soldier must be honored by his monarch even in his last hour: therefore, permit me to give you the place of honor,” and Miramon had to place himself in the middle.

An officer and seven men now stepped forward, until within a few yards of each of the three condemned. The Emperor went up to those before him, gave each soldier his hand and a maximilian d’or [three dollars twenty-seven cents], and said, “Muchachos [‘ boys ’], aim well, aim right here,” pointing to his heart. Then he returned to his stand, took off his hat, and wiped his forehead with his handkerchief. This and his hat he gave to Tudos, with the order to take them to his mother, the Archduchess Sophia. Then he spoke with a clear and firm voice the following words:

MEXICANS:

Persons of my rank and origin are destined by God to be either benefactors of the people or martyrs. Called by a great part of you, I came for the good of the country. Ambition did not bring me here; I came animated with the best wishes for the future of my adopted country, and for that of my soldiers, whom I thank, before my death, for the sacrifices they made for me. Mexicans, my blood be the last that shall be spilled for the welfare of the country; and if it should be necessary that its sons shall still shed theirs, may it flow for its good, but never by treason. Viva independence! Viva Mexico!”

Looking around, the Emperor noticed, not far from him, a group of men and women who sobbed aloud. He looked at them with a mild and friendly smile, then he laid both his hands on his breast and looked forward. Five shots were fired, and the Emperor fell on his right side, whispering slowly the word, “Hombrel ” (“ O Man!”). All the bullets had pierced his body, and each of them was deadly; but the Emperor still moved slightly. The officer laid him on his back, and pointed with the point of his sword on the Emperor’s heart. A soldier then stepped forward, and sent another bullet into the spot indicated.

Neither the Emperor nor Miramon nor Mejia had his eyes bandaged. Miramon, not addressing the soldiers, but the citizens assembled, said: “Mexicans: my judges have condemned me to death as a traitor to my country. I never was a traitor, and request you not to suffer this stain to be affixed to my memory, and still less to my children. Viva Mexico! Viva the Emperor! ” When the shots hit him he died instantly.

Mejia only said, “Viva Mexico! Viva the Emperor!” He lived after the firing, and two more bullets were necessary to dispatch him. All the three condemned were shot at the same moment.

| <—Previous | Master List |

This ends our selections on Mexico Rejects Maximilian by two of the most important authorities of this topic:

- History of Modern Europe by Charles A. Fyffe published in 1890.

- My Diary in Mexico by Felix Salm-Salm published in 1868.

Charles A. Fyffe began here. Felix Salm-Salm began here.

This site features short and lengthy pieces on all aspects of our shared past. Here are selections from the great historians who may be forgotten (and whose work have fallen into public domain) as well as links to the most up-to-date developments in the field of history and of course, original material from yours truly, Jack Le Moine. – A little bit of everything historical is here.

More information on Mexico Rejects Maximilian here and here and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.