The fact is that the China of yesterday is farther away from the China of to-day than are the days of Washing ton from the United States of the present time.

Continuing China Awakens 1905,

Today we begin the second part of the series with our selection by Adachi Kinnosuke. The selection is presented in 2.5 easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Adachi Kinnosuke presents the contemporary Japanese point of view.

Previously in China Awakens 1905.

Time: 1905

Place: China

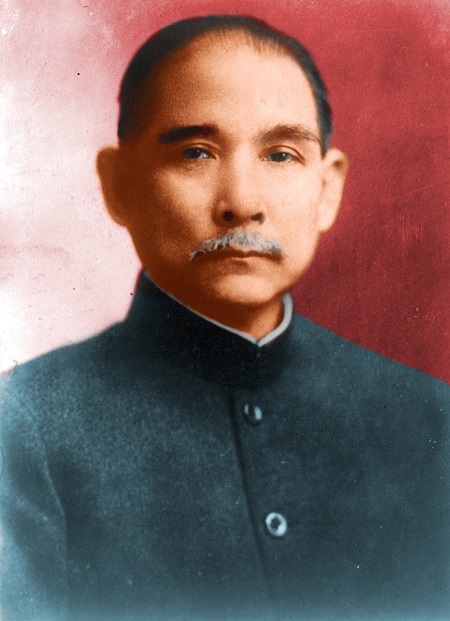

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

The year 1905, so eventful to Nippon [Japan], is to China a great year indeed. From all indications, China is likely to look back upon this year as we of Nippon look back upon 1868. That was the birth-year of the New Nippon, the first year of the present period of Meiji. Now that she is able to do so, the end and aim of Nippon effort seems to be to bring China to herself, to make her know what she is. On the fine morning when China finds herself — if only we could bring about this simple consummation so devoutly prayed for — the vivisection of the Chinese Empire may appeal to the sense of humor of enlightened Europeans, but never to their territorial ambitions. And already many voices, much more eloquent than the voice of a prophet crying in the wilderness, are telling us of the breaking of the dawn of a new day for China. The fact is that the China of yesterday is farther away from the China of to-day than are the days of Washing ton from the United States of the present time.

Not so many years ago, a French fleet went up the Min River and anchored within ten miles of the city of Foochow. A short time prior to that, France had a little trouble with the people of Tonquin. The French wanted to rob them of their native land; and, to their honor, the inhabitants fought for it against the French. France suspected that the Chinese Government might have done something to encourage this outlandish sentiment — which in other countries bears the beautiful name of patriotism. That is to say, France suspected that the Government of China might have done its duty toward the people of Tonquin. Through her Minister in Peking, France had demanded an indemnity; and this Christian power was dumfounded to see that China was not in a hurry to pay an indemnity for being so reckless as to dare to do her duty to the people of Tonquin. And the presence of the French fleet in the Min River was one of the usual arguments which civilized Europe used to employ in those days. To the still greater amazement of both the French Minister at Peking and the country he represented, China declined to apologize with a pretty heap of gold for one of the few right things she had done. The French Minister turned to the French admiral of the fleet, anchored in the Min River; and without the slightest intimation of war, the French fired upon the pitiful Chinese fleet which was trying to defend the city of Foochow. Three thousand Chinese bodies floated out to sea and came back into the river with the return of the tide; and for days the mutilated remains of the dead sailors of China spoke with gruesome eloquence of the humanity and manly justice of civilized France!

On November 1, 1897, in the Province of Shantung, two German missionaries who went into China without an invitation were killed. One might suppose that their Government would have taken a rather philosophical view of this incident, regrettable in the extreme though it was. Such, however, was far from the case; for on the 14th of that month, German marines were landed at Kiaochau, and, through the famous treaty signed on March 6, 1898, the world saw how Germany received what she considered a fair price for the misfortune of the two missionaries, namely, the cession of the finest deep harbor on the Chinese littoral; 3,000 taels of indemnity; the dismissal of the Governor of the Province of Shantung; the building of three “expiatory’ chapels; concessions for the building of two railways in the province; and the exclusive right of exploiting the mineral resources of the province within twenty kilometers of the railroad on both sides — all of which goes to show that the Kaiser sets a great value upon the lives of the pious men under his flag.

After that, the Chinese officials took the liberty of informing the Germans in the Shantung province of the feverish condition of the people, and of their feelings toward foreigners in general and Germans in particular; and they told them, moreover, with extremely un-Chinese frankness, that the interior of the province was not at all a healthy place for the Germans to take their holiday trips in. A few Germans, three of them, I think, wishing to prove how enterprising they could be when it came to serving their Kaiser in his laudable work of sending the German flag to all sorts of places where it had not the slightest business to be, laughed at the warning of the Chinese officials and wandered into the interior, whence they were barely able to escape with their lives. The German commander at Kiaochau also went into the interior. However, being a wise man, he did not go alone, but took with him many guns. On his trip he burned two villages, and did not even take the trouble to count the number of Chinese he killed. Of course, such a thing as the Germans paying for the Chinese lives a millionth part of the price that the Germans required the Chinese to pay for the fright of their own pious countrymen never entered his head. Germans required the Chinese to pay for the fright of their own pious countrymen never entered his head.

Now, the Kaiser, who knows the word of God, and, judging by what I have read, uses it not too rarely, did not even frown very harshly upon the act of the commander at Kiaochau in destroying their homes or killing a large number of villagers who had not the slightest hand in the high-priced luxury of threatening the lives of the three foolish Germans. Perhaps, in his heart, the Kaiser very much regretted the unhappy incident; but this did not cause him to overlook the fact that the affair might be turned to good account. He had been trying for many years to convince his people of the importance of building a formidable navy, while for some reason or another the people, on their part, had failed to be convinced by his eloquence of the necessity of spending so many millions for that purpose. But this incident showed clearly how necessary it was to possess a formidable fleet in order to maintain the dignity of the German flag on a distant sea, and how, without it, it would be impossible to carry out the great policy of trade expansion in the far East with which he had been baiting the commercial imagination of the Germans. In a word, the Kaiser could well afford to pay a few marks for the lives of the defenseless Chinese villagers, as well as the entire cost of the two villages that had been burned. But, of course, China did not receive a tael from the Power to which she had paid the price above mentioned for the loss of only two very rash men.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Wu Ting Fang begins here. A Chinese Cambridge Man begins here

More information here and here.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.