The most important of all the ancient materials for writing upon were papyrus, parchment, and vellum; and on these substances nearly all our most valuable manuscripts were written.

Continuing Early History of Printing,

our selection from Origin and Progress of Printing by Henry George Bohn published in 1857. The selection is presented in eleven easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Early History of Printing.

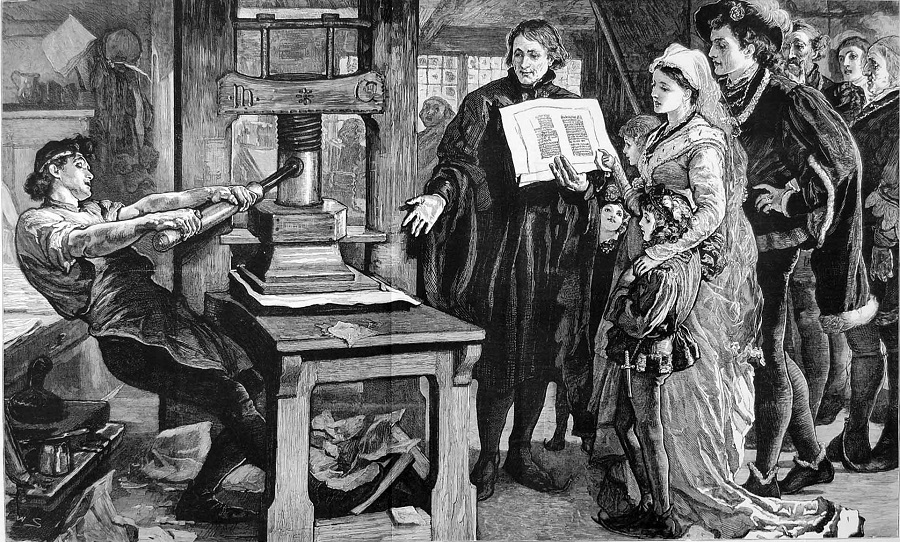

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

Next seems to have followed writing or engraving on stone, wood, ivory, and metals, of which we have many early evidences. The Decalogue, or the Ten Commandments, given by God to Moses on Mount Sinai, was originally, we are told in the Bible, written upon two tables of stone; the pillars of Seth were of brick and stone; the laws of the Greeks were graven on tables of brass, which were called cyrbes. Herodotus mentions a letter written with a style on stone slabs, which Themistocles, the Athenian general, sent to the Romans about B.C. 500; and we have another evidence of the same period still existing — the so-called Borgian inscription, which is a passport graven in bronze, entitling the holder to hospitable reception wherever he demanded it. Upward of three thousand of such engraved tablets, including the famous Roman laws of the Twelve Tables, were consumed in the great fire which destroyed the Capitol in the time of Vespasian.

I could cite a great many other evidences of early writing on stone or brass, but will merely recommend you to see the Rosetta inscription, which is conspicuously placed in the British Museum. It is this very interesting stone which, being partly Greek and partly Egyptian, has enabled us to decipher so many Egyptian monuments.

Pliny informs us that table-books of wood — generally made of box or citron wood — were in use before the time of Homer, that is, nearly three thousand years ago; and in the Bible we read of table-books in the time of Solomon. These table-books were called by the Romans pugillares, which may be translated “hand-books”; the wood was cut into thin slices, finely planed and polished, and written upon with an iron instrument called a stylus. At a later period, tables, or slices of wood, were usually covered with a thin layer of hard wax, so that any matter written upon them might be effaced at pleasure, and the tables used again. Such practice continued as late as A.D. 1395. In an account roll of Winchester College of that year we find that a table covered with green wax was kept in the chapel for noting down with a style the daily or weekly duties assigned to the officers of the choir. Ivory also was used in the same way.

Wooden table-books, as we learn from Chaucer, were used in England as late as the fifteenth century. When epistles were written upon tables of wood they were usually tied together with cord, the seal being put upon the knot. Some of the table-books must have been large and heavy, for in Plautus a schoolboy seven years old is represented as breaking his master’s head with his table-book.

Writing seems also to have been common, at a very early period, on palm and olive leaves, and especially on the bark of trees — a material used even in the present time in some parts of Asia. The bark is generally cut into thin flat pieces, from nine to fifteen inches long and two to four inches wide, and written on with a sharp instrument. Indeed, the tree, whether in planks, bark, or leaves, seems in ancient times to have afforded the principal materials for writing on. Hence the word codex, originally signifying the “trunk or stem of a tree,” now means a manuscript volume. Tabula, which properly means a “plank” or “board,” now also signifies the plate of a book, and was so used by Addison, who calls his plates “tables.” Folium (“a leaf”) has given us the word “folio”; and the word liber, originally meaning the “inner bark of a tree,” was afterward used by the Romans to signify a book; whence we derive our words, “library,” “librarian,” etc. One more such etymology, the most interesting of all, is the Greek name for the bark of a tree, biblos, whence is derived the name of our sacred volume.

Before I leave this stage of the subject, I will mention the way in which the Roman youth were taught writing. Quintilian tells us that they were made to write through perforated tablets, so as to draw the stylus through a kind of furrow; and we learn from Procopius that a similar contrivance was used by the emperor Justinian for signing his name. Such a tablet would now be called a stencil-plate, and is what to the present day is found the most rapid and convenient mode of marking goods, only that a brush is used instead of an iron pen or style.

Writing and materials have so much to do with the invention of printing that I feel obliged to tarry a little longer at this preliminary stage. The most important of all the ancient materials for writing upon were papyrus, parchment, and vellum; and on these substances nearly all our most valuable manuscripts were written. Papyrus, or paper-rush, is a large fibrous plant which abounds in the marshes of Egypt, especially near the borders of the Nile. It was manufactured into a thick sort of paper at a very early period, Pliny says three centuries before the reign of Alexander the Great; and Cassiodorus, who lived in the sixth century, states that it then covered all the desks of the world. Indeed, it had become so essential to the Greeks and Romans that the occasional scarcity of it is recorded to have produced riots. Every man of rank and education kept librarii, or book-writers, in his house; and many servi, or slaves, were trained to this service, so that they were a numerous class.

Papyrus is a very durable substance, made of the innermost pellicles of the stalk, glued together transversely, with the glutinous water of the Nile. It was for many centuries the great staple of Egypt, and was exported in large quantities to almost every part of Europe and Asia, but never, it would appear, to England or Germany. After the seventh century its use was gradually superseded by the introduction of parchment; and before the end of the twelfth century it had gone generally out of use. From “papyrus” the name of “paper,” which, with slight variations, is common to many languages, is no doubt derived.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.