This series has eight easy 5 minute installments. This first installment: Earliest Polar Explorers.

Introduction

Even though the North Pole was closer the Europe than many other destinations that they explored, it remained to the twentieth century before it was reached. Horne’s article celebrates Peary’s accomplishments but was he the first to reach the Pole? Modern authorities question this. After reading the article, check out the links below.

First, we take up the attempts during the centuries before this.

This selection is from The Great Events by Famous Historians, Volume 20 by Charles F. Horne published in 1914. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Charles F. Horne (1870-1942) was a Professor of English at City College of New York who wrote over a hundred books, mostly histories.

Place: Northern Seas

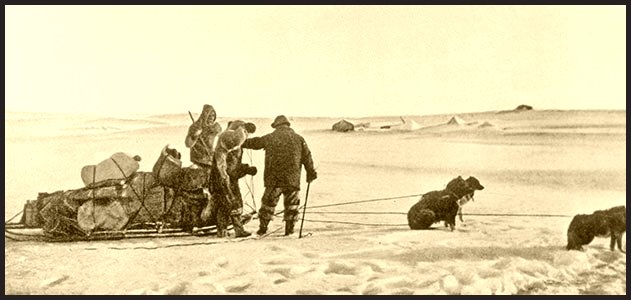

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

Othere, the old sea-captain,

Who dwelt in Helgoland,

To King Alfred, the Lover of Truth,

Brought a snow-white walrus-tooth,

Which he held in his brown right hand.”

Thus Longfellow opens his poem which tells of the beginning of Arctic exploration. In the year 886, or there-abouts, Othere, a Norse chieftain, narrated to King Alfred of England, and Alfred wrote down in a book, an account of his daring voyage in the desolate ocean north and east of Norway. Othere is the first man known to have crossed the seventieth parallel of northern latitude. He rounded North Cape, the extreme point of the European continent, and continued for three days into the unknown beyond, seeking rather, it would seem, to satisfy his own desire for knowledge than to gain any personal profit. Thus Othere stands not only as the beginner, but as the typical figure, the first self-sacrificing hero of Arctic exploration.

The Norsemen were the earliest known adventurers into the North. Others among them beside Othere felt that longing to know. Iceland, Southern Greenland, and Labrador were all discovered by their tiny shallops. Such regions can hardly be classed as “Arctic” since they are fully habitable; but the settlers in Greenland are known to have pushed their way far up its western coast, and to have hunted the whale and the walrus there. One of their “runic” stones has been found above the seventy-third parallel, bordering the very waters by which Peary has at last penetrated to the Pole. Moreover, we have such accounts as that about King Harold Hardrada, one of the greatest of Norway’s kings, who sailed to the North with all his ships until “darkness hung above the brink where the world falls away, and the king turned back just in time to escape being drawn into the abyss.” These vague tales are indeed wrapped in that mystery of wonderment in which the Norsemen lived, but they show also much keen observation and practical knowledge of the Arctic ice fields.

Modern exploration of the far North begins with the discovery of America. It is perhaps seldom sufficiently emphasized that this discovery was a disappointment, especially to Teutonic Europe. The explorers were not looking for America, but for a road by which trade might reach the wealth of India — and they would much sooner have found what they sought. To the mercantile view, America was simply an obstacle blocking the way to India. Spain indeed profited from the new world; but England and Holland, at first, merely tried to get around it. Hence there was search all along the coast for an opening to sail through. No direct western passage existed; and though the search for a “Southwest passage” was successful, Magellan passing below South America and reaching the Asiatic goal, yet the route involved many months of southward journey and terrific danger from the most tempestuous seas in the world. Hence the “Northwest passage,” and, failing that, the “Northeast passage” going northward around Europe itself, were eagerly and determinedly sought.

John and Sebastian Cabot, the earliest English discoverers of America, started their voyage to find this Indian passage (1497), and sailed with watchful merchant eyes far up the bleak coast of Labrador. More than half a century later, Sebastian, grown old in voyaging for other lords, was summoned back to England and made governor of a company of “Merchant Adventurers” to renew the unsuccessful search. Mindful of his own failure on the American coast, Sebastian determined to have the Northeast route attempted. For this purpose he sent out (1553) an expedition of three ships under Sir Hugh Willoughby. Thus was begun the exploration of the northern Asiatic coast.

The expedition produced important results, but it also involved a disaster, the first of those awful tragedies of suffering wherewith Arctic history is overfilled. Willoughby with two of the ships became separated from the other. Pressing on, he discovered the coast of Nova Zembla; then, driven back by the winter ice, he and his crew established themselves for the winter upon the desolate Arctic shore of Lapland or European Russia. This, the first winter passed by a ship’s crew in the world of ice, revealed the worst of the grim horrors which so many brave sailors have since encountered there. Scurvy, that dread disease which comes from lack of fresh food, at tacked Willoughby and his men. Their flesh grew foul, and rotted. One by one they died, without knowing either the origin or the cure of their hideous malady. Not one among them all survived till spring. Only by the records that they left, have later generations learned their piteous fate.

Meanwhile, the third ship of the expedition, under Captain Richard Chancellor, penetrated the White Sea and reached what is now Archangel, the port of Russia on the northern ocean. Russia did not then, as now, border upon other seas, the Baltic and the Black; she had no sea communication whatever with other lands; and when this bold adventurer appeared from out the northern wastes, he was hailed as a great benefactor. That long winter which Willoughby spent in dying on a barren coast, Chancellor spent in feasting at the Russian capital of Moscow. And when in spring Chancellor sailed back to England, he had established between the two countries a traffic vastly and mutually beneficial, which continued until Russia fought her way to more accessible shores.

Other explorers soon pushed beyond Willoughby’ s Nova Zembla goal. Most notable among them was Willem Barents, who made several voyages under the flag of Holland. In 1596 he discovered the islands of Spitzbergen, and then rounded the northern point of Nova Zembla. Beyond this, his ship was caught in the ice, and he and his mates were imprisoned for the winter in a bay upon Nova Zembla’s eastern coast. Here, above the seventy-sixth parallel, they are the earliest men known to have endured and survived an Arctic winter, with its months of sunless night, its eternal cold, and its ever- present menace of starvation. They had the fresh meat of polar bears to save them from scurvy; indeed they had more bears for company than they liked, and fought some desperate battles against the hungry monsters. They found driftwood to build them a hut and keep a fire; but they almost perished of the cold. Their chronicle tells of marvelous courage and deep religious spirit. Barents himself, their only navigator, died in the spring, worn out with toil. Their tiny ship was so crushed by the ice as to be useless; so, in open boats, they made their way a thousand miles back to the shores of Lapland, where the survivors found the succor they had so heroically deserved.

| Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.