We turn now to the three most recent and most successful of Arctic conquerors, Nansen, Abruzzi, and Peary.

Continuing The Search for the North Pole,

our selection from The Great Events by Famous Historians, Volume 20 by Charles F. Horne published in 1914. The selection is presented in eight easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in The Search for the North Pole.

Place: Arctic Ocean

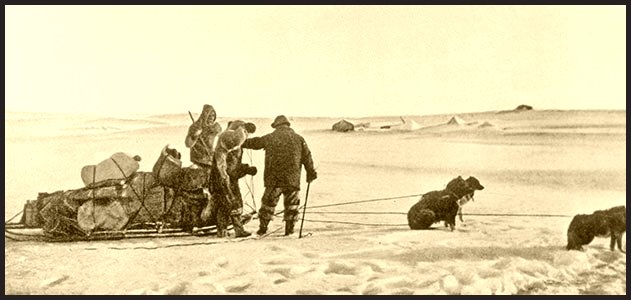

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

Thus, modern methods were established. Nordenskiold began the system of pushing forward by a series of preparatory voyages. Markham started the recent sledge expeditions. The Tegetthoff had encountered the first of some notable drifting experiences. Most tragic of these drifting trips was that of the American ship Jeanette. She set out from San Francisco in 1879, under the charge of Commander De Long, to attempt the Pole by way of Behring Strait. Forcing her way among the ice floes in this little-known region of the Arctic seas, she was finally caught in the great pack of ice. She drifted with it, helpless and immovable, for two years. The general drift was westward and a little toward the north. Some small and barren islands above the Asiatic continent were discovered, and it was proved that the Arctic here was a broad but shallow sea. Several times the ice partly opened, and then in enormous masses crushed in again upon the ship until she was completely ruined. One last time the ice opened, and the battered Jeanette sank forever. With sledges and boats her crew forced their way to the Siberian Islands, and thence to the mainland at the mouth of the Lena River. Only one small boat-load of the men survived that terrible journey. Another boat, commanded by De Long, reached the coast, but his party perished of starvation, one by one, before they could attain to food or help.

In 1879 was held the First International Circumpolar Conference, in which ten great nations took part, including all which had been prominent in Polar history. It was agreed that each nation should establish one or more polar stations which might be made bases of supply and from which exploration could be more effectively pushed onward.

Most notable and most northern of these stations was that established by the United States, under command of Lieutenant Greely. It was planted in 1881 on the shore of Lady Franklin Bay, which lies on the Smith Sound route far up above the eighty-first parallel, almost up to the polar sea where Nares had wintered in 1875. Here Greely and his companions spent two winters, those of 1881-2 and 1882-3. In the intervening summer they explored the coasts to the northward; and Lieutenant Lockwood, following up the Greenland coast almost to its farthest north, reached a latitude of 83°24’, even higher than Markham’s highest.

Then came the tragedy. The summer of 1883, the third which the heroic investigators had spent in those awesome wilds, brought no ship to take them home. They had expected one both that year and the year before; but inclement seasons, a wreck, and other delays had driven the relief ships back. Now it became necessary for Greely and his men to save themselves, fight their own way back toward civilization as best they might. They worked their way that summer back down Smith Sound to Baffin Bay; but here the winter overtook them. Poorly sheltered, worse provisioned, they suffered through terrible months of cold and darkness and starvation. When a relief expedition found them the following June more than half had died, the rest were almost dying.

We turn now to the three most recent and most successful of Arctic conquerors, Nansen, Abruzzi, and Peary. There is a striking similarity between the careers of Nansen and Peary. Each devoted himself to the North for many years, and through a number of trips. Each began his work in the later ‘8o’s, and each started by exploring the before untrodden interior of Greenland. Dr. Fridtiof Nansen, a young Norwegian scientist born in 1861, crossed the southern end of Greenland in 1888, at about the latitude of the Arctic Circle. He was accompanied by four companions. Landing on the east coast they toiled up the gigantic ice mountains, crossed the central divide of the mighty island at a height of 9,000 feet, and then with comparative ease coasted down to the western shore.

After some further experiences, Nansen persuaded the Norwegian government to aid him in what was perhaps the most daring of all Arctic ventures. The Jeanette, as we have seen, had been wrecked after entering Bering Strait. Some drifted fragments from the expedition were found, years afterward, upon the Greenland coast. The supposition was that these must have floated across the Polar Sea, perhaps across the very Pole itself, and that, therefore, a current flowed that way. Nansen resolved to commit himself to that suppositious current, in hopes that he, too, might cross the Pole. For this purpose a ship, the Fram, in English the Forward, was built of special stoutness to resist the crushing of the ice. She was provisioned for five years, and in 1893 set out under command of Nansen and Captain Sverdrup to commit herself to her fate. Steaming northeast along the Asiatic coast, Nansen forced his way into the Arctic ice not far from where the Jeanette had sunk.

At first, much to her commander’s disappointment, the Fram drifted southwest. Later, however, the ice turned north ward, and followed about the direction he had hoped. For three years the Fram floated with the pack, and though she never reached the Pole, she did, in the fall of 1895, reach a latitude far higher than man or ship had ever been before, almost to the eighty-sixth degree. In the summer of 1896 she found herself drifting southward again, north of Spitzbergen. Here, after long and desperate blasting with explosives, she broke her way clear of the ice and returned to Norway.

Nansen himself, however, had not continued in the Fram. In the early spring of 1895 ^e became convinced that the ship would never drift much higher, and with one companion, Johansen, he adopted the yet more daring expedient of abandoning the comparative security of the ship and pushing north ward with two sledges drawn by dogs. These two reckless adventurers left the Fram in March, at about latitude 840. They had no hope of ever finding the ship again in that limitless expanse, but planned, after pushing as far northward as they could, to march back across the ice to the archipelago of Franz Josef Land. This they ultimately did. Pushing forward, sometimes over water channels or “leads” in the ice, some times over soft snow and slush, sometimes over bergs so rifted and broken as to be a constant climb, they reached to north latitude 86°i^. Their advance of about a hundred and fifty miles had taken them nearly a month. Nansen kept careful count of their provisions and of their daily perishing dogs, and he decided that he had reached the farthest limit from which he might still hope to return. Therefore, he turned back; and after countless dangers, privations, and almost miraculous escapes, he and his companion reached Franz Josef Land more than three months later. They wintered there, in solitude and almost starvation. The next spring they were rescued by another exploring party, so that they got back to Norway just a week ahead of their comrades in the Fram.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.