Steam had now superseded sails as the motive power of ships, so Franklin had high hopes that the glory of the achievement was to be his.

Continuing The Search for the North Pole,

our selection from The Great Events by Famous Historians, Volume 20 by Charles F. Horne published in 1914. The selection is presented in eight easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in The Search for the North Pole.

Place: Arctic North

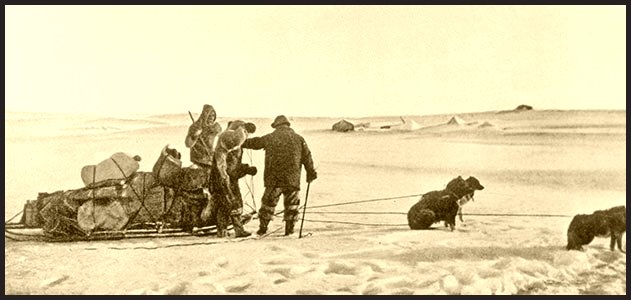

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

In 1845 the English government sent out the renowned and ill-fated Franklin expedition. What Franklin himself accomplished was little, but the numerous search expeditions dispatched to his rescue completed the investigation of the islands north of America and at last accomplished the aim of four hundred years, the discovery of the Northwest passage. Sir John Franklin had already achieved renown in the North, and was almost sixty years old when the command of his final expedition was offered him. Despite his age he eagerly accepted the responsibility and opportunity, and set forth to discover the ever-elusive road to the Northwest. Steam had now superseded sails as the motive power of ships, so Franklin had high hopes that the glory of the achievement was to be his. Passing westward as Parry had done through Lancaster Sound, he turned southward through straits which might indeed have led him to the open sea and Behring Strait. But the winter ice froze fast about his ship, so fast indeed that the next summer failed to free her from her prison. Franklin died. Another summer came, but also failed to free the ship. Then her crew, abandoning her, attempted to reach the Ameri can mainland to the southward. They attained, barely attained, that barren shore, exhausted and starving. They could go no further; and there, twenty years later, their bleaching skeletons were found by a searching party under the American Lieutenant Schwatka.

It was useless to reckon all the rescue expeditions which at tempted to follow Franklin’s track. The English government sent several; the explorer’s wife, Lady Franklin, financed others; at least three were dispatched from the United States. Gradually one trace after another of the missing men was found, but far too late to aid the dead. Two English ships, sent by way of the Pacific, pushed east from Behring Strait till they reached the western shores of the Arctic Archipelago. One of these ships under Captain McClure penetrated the archipelago eastward to within sight of Melville Island, which Parry had reached from the other side. Here McClure’ s ship, like Franklin’s, became locked inescapably in the winter’s ice; but the men of another rescue expedition coming from the east brought McClure and his crew back to England. Thus they, if not their ship, did actually complete the trip through the Northwest passage. They entered Bering Strait in the summer of 1850 and reached England, some of them in the fall of 1853, others in 1854. The other ship which had accompanied McClure also returned to England in 1854. Under her captain, Collinson, she had penetrated even farther eastward than McClure, reaching in fact to within a few miles of where Franklin’s crew had perished, but turning back before the impassable ice. Having practically circumnavigated the American continent, Collinson then sailed back through all the vast region he had traversed. Thus, the Northwest passage had actually been found, but was proved useless. McClure was knighted for his achievement.

American exploration of the far North began with the expeditions sent out in search of Franklin. The first of these was financed by Mr. Henry Grinnell, a New York merchant. The Americans turned their attention at once to the passage up Smith’s Sound by which they have at last achieved the Pole. The first search expedition, under De Haven, looked up this waterway; the second, under Dr. Elisha Kent Kane, wintered on its shores (1853), having penetrated farther north than anyone had before attained by this route. We know now, that here to the northwest of Greenland one narrow strait succeeds another for over two hundred miles. Above Smith Sound comes Kane Sea, then Kennedy Channel, Hall Basin, Robeson Channel, and at last Lincoln Sea and the Arctic Ocean. But Kane did not know of this, he hoped and believed that from the sea named after him the Arctic waters stretched away unbounded to the Pole. Some of his men who travelled north of the eightieth parallel assured him of this, and of the ice- free condition of the waters. So, after two disastrous winters, Kane returned home to spread abroad the faith in an “open polar sea.” One of his assistants, Dr. Hayes, penetrated yet a little farther in a later expedition. And then in 1872 Mr. Charles Hall in his ship, the Polaris, steamed on up the broadening channel to 82° 6’, reaching almost to its end before he was stopped by the ice.

We approach the most recent period of the Arctic struggle. In 1874 an Austrian expedition was sent out to try the northern route least tested of all, that to the northward of Nova Zembla. The fate of this, the Tegetthoff expedition under Lieutenant Weyprecht, was peculiar. Before the ship had even reached Nova Zembla, it was caught in the drift ice and became firmly embedded. Helpless, immovable, a part of the ice floe, the ship drifted for over a year, northward and eastward, until at length the wanderers were cast upon the hitherto undiscovered coast of Franz Josef Land. From there they finally escaped in open boats.

The next year (1875) the noted Finnish explorer, Nordenskiold, began his series of trips toward the northeast. His goal was the Northeast passage, the outline of which along the Asiatic coast had been mapped out in the previous century, but which no ship had ever completely covered. The necessities of Arctic exploration were now beginning to be appreciated and scientifically approached. Nordenskiold made several preliminary voyages, feeling his way, testing his route. Finally, in 1878 he set out from Tromso in Norway, passed south of Nova Zembla and steamed on eastward to within about a hundred miles of Behring Strait. Here the winter ice closed around him; but with the coming of the next summer he completed his voyage, steaming forth upon the Pacific Ocean. Thus, the Northeast passage has been actually voyaged by a ship, as the Northwest never has and perhaps never will be. For all commercial purposes one is well-nigh as dangerous and as useless as the other.

Another expedition which set out in 1875 was sent forth by the English government under Captain Nares. Its effort was to reach the Pole, west of Greenland. Captain Nares essayed the Smith Sound route, and, penetrating even farther than Hall in the Polaris, reached the far northern sea beyond the series of narrow channels there. On this bleak shore Nares wintered. The sea proved, however, not open as Hall had thought, but eternally ice-covered. The next spring, one of Nares’ officers, Lieutenant Markham, led a party forth upon the frozen sea, attempting to do what Parry had tried fifty years before, what Peary has at length accomplished, reach the Pole by marching over the ice floes. Markham dragged both boats and sledges, but even thus encumbered he reached to 83°20′, overtopping the mark Parry had set so long before.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.