Today’s installment concludes Early History of Printing,

our selection from Origin and Progress of Printing by Henry George Bohn published in 1857.

If you have journeyed through all of the installments of this series, just one more to go and you will have completed a selection from the great works of eleven thousand words. Congratulations! For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Early History of Printing.

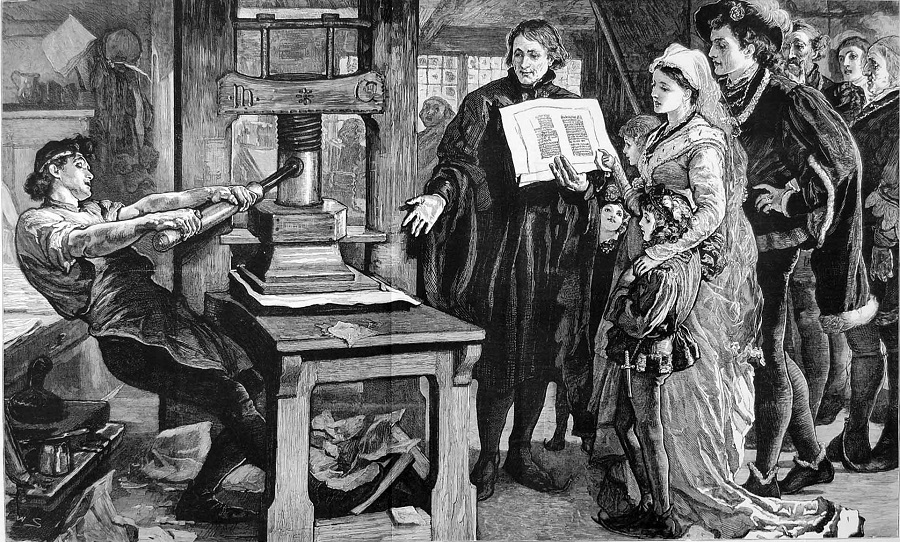

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

But the time had not come; for without a very large demand, such as could not exist in those days, stereotyping would be of no advantage. Books which sell by hundreds of thousands, and are constantly reprinting, such as Bibles, prayer-books, school-books, Shakespeares, Bunyans, Robinson Crusoes, Uncle Toms, and very popular authors and editions, will pay for stereotyping; but for small numbers it is a loss. After the invention had been neglected long enough to be forgotten, Earl Stanhope, who had for several years devoted himself earnestly to the subject, and made many experiments, resuscitated it, in a very perfect manner, in 1803; and his printer, Mr. Wilson, sold the secret to both universities and to most of the leading printers. To the art of stereotyping the public is mainly indebted for cheap literature, for when the plates are once produced the chief expense is disposed of.

Something akin to stereotyping is another method of printing, called logography, invented by John Walter of the London Times, in 1783, and for which he took out a patent. This means a system of printing from type cast in words instead of single letters, which it was thought would save time and corrections when applied to newspapers, but it was not found to answer. A joke of the time was a supposed order to the type-founder for some words of frequent occurrence, which ran thus: “Please send me a hundredweight, sorted, of murder, fire, dreadful robbery, atrocious outrage, fearful calamity, alarming explosion, melancholy accident; an assortment of honorable member, whig, tory, hot, cold, wet, dry; half a hundred weight, made up in pounds, of butter, cheese, beef, mutton, tripe, mustard, soap, rain, etc., and a few devils, angels, women, groans, hisses, etc.” This method of printing did not succeed; for if twenty-four letters will give six hundred sextillions of combinations, no printing-office could keep a sufficient assortment of even popular words.

But before the middle of the sixteenth century printing was introduced into Spanish America. Existing books show that in Mexico there was a press as early as 1540; but it is impossible to name positively the first book printed on this continent. North of Mexico the first press was used, 1639, by an English Non-conformist clergyman named Glover. In 1660 a printer with press and types was sent from England by the corporation for propagating the gospel among the Indians of New England in the Indian language. This press was taken to a printing-house already established at Cambridge, Mass. It was not until several years later that the use of a press in Boston was permitted by the colonial government, and until near the end of the seventeenth century no presses were set up in the colonies outside of Massachusetts.

In 1685 printing began in Pennsylvania, a few years later in New York, and in Connecticut in 1709. From 1685 to 1693 William Bradford, an English Quaker, conducted a press in Philadelphia, and in the latter year he removed his plant to New York. He was the first notable American printer, and became official printer for Pennsylvania, New York, New Jersey, Rhode Island, and Maryland. His first book was an almanac for 1686. In 1725 he founded the New York Gazette, the first newspaper in New York. But the first newspaper published in the English colonies was the Boston News-Letter, founded in 1704 by John Campbell, a bookseller and postmaster in Boston. Only four American periodicals had been established when, in 1729, Benjamin Franklin, who was already printer to the Pennsylvania Assembly, became proprietor and editor of the Pennsylvania Gazette.

Until the last quarter of the eighteenth century the progress of printing in America was slow. But in 1784 the first daily newspaper, the American Daily Advertiser, was issued in Philadelphia, and from this time periodical publications multiplied and the printing of books increased, until the agency and influence of the press became as marked in the United States as in the leading countries of Europe.

Even since the time when Bohn wrote, the progress made in various branches of the printer’s art has been such as might have astonished that famous publisher of so many standard works. The twenty-first century has seen printing in electronic form with ebooks and websites such as this one.

Recent improvements for increasing the capacity of the press, and often the quality of its productions, are quite comparable to those which our own time has seen in other departments of industry, as in the applications of electricity and the like. In addition to the further development of stereotyping, there has been marvelous improvement in nearly all the machinery and processes of printing. This is especially marked in rapid color-printing, and in the successors of inadequate typesetting-machines — in the linotype, the monotype, the typograph, etc.

Most wonderful of all, perhaps, is the improved printing-press itself, in various classes, each adapted to its special purpose. The sum of all improvements in this department of mechanical invention is seen in the great cylinder-presses now in general use, especially the one known as the web perfecting press. This is a machine of great size and intricate construction, which yet does its complex work with an accuracy that almost seems to denote conscious intelligence. It prints from an immense roll of paper, making the impression from curved stereotype plates, runs at high speed, prints both sides of the paper at one run, and folds, pastes, and performs other processes as provided for. By doubling and quadrupling the parts, the ordinary speed of about twenty-four thousand impressions an hour may be increased to one hundred thousand an hour. The multicolor web perfecting press prints four or more colors at one revolution of the impression cylinder.

To meet the demands of such an enormous consumption of paper as the modern press requires, it was necessary to invent other processes and to utilize more abundant and cheaper material for paper-making than those formerly employed. This requirement has been supplied in recent years mainly through the extensive manufacture of paper from wood-pulp. This method, together with improved processes in the use of other materials, has removed all fear of a paper famine such as has sometimes threatened the printing industry in the past.

| <—Previous | Master List |

This ends our series of passages on Early History of Printing by Henry George Bohn from his book Origin and Progress of Printing published in 1857. This blog features short and lengthy pieces on all aspects of our shared past. Here are selections from the great historians who may be forgotten (and whose work have fallen into public domain) as well as links to the most up-to-date developments in the field of history and of course, original material from yours truly, Jack Le Moine. – A little bit of everything historical is here.

More information on Early History of Printing here and here and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.