The principal movements have been in stereotyping, electrotyping, the improvement of presses, and the application of steam power.

Continuing Early History of Printing,

our selection from Origin and Progress of Printing by Henry George Bohn published in 1857. The selection is presented in eleven easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Early History of Printing.

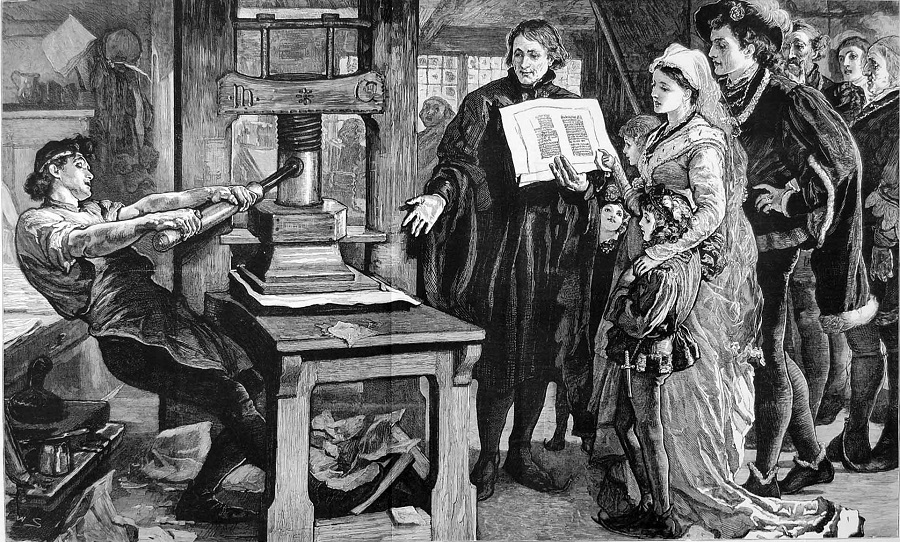

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

Minstrels, instead of books, were in early times the principal medium of communication between authors and the public; they wandered up and down the country, chanting, singing, or reciting, according to the taste of their customers, and had certain privileges of entertainment in the halls of the nobility.

It may be wondered that Caxton, like many of the foreign printers, did not begin with, or at least some time during his career print, the Scriptures, especially as Wycliffe’s translation had already been made. But there were good reasons. Religious persecution ran high, and the clergy were extremely jealous of the propagation of the Scriptures among the people. Knighton had denounced the reading of the Bible, lamenting lest this jewel of the Church, hitherto the exclusive property of the clergy and divines, should be made common to the laity; and Archbishop Arundel had issued an enactment that no part of the Scriptures in English should be read, either in public or private, or be thereafter translated, under pain of the greater excommunication. The Star Chamber, too, was big with terrors. A little later, Erasmus’ edition of the New Testament was forbidden at Cambridge; and in the county of Surrey the Vicar of Croydon said from the pulpit, “We must root out printing, or printing will root out us.”

Winkin de Worde, who had come in his youth with Caxton to England and continued with him in the superintendence of his office to the day of his death, succeeded to the business, and conducted it with great spirit for the next forty years. He began by entirely remodelling his fonts of Gothic type, and introduced both Roman and Italic; became his own founder, instead of importing type from the Low Countries; promoted the manufacture of paper in this country; and such was his activity that he printed the extraordinary number of four hundred eight different works. He deserves, perhaps, more praise than he has ever received for the important part he played in establishing and advancing the art in England.

But no one of our early printers deserves more grateful remembrance than Richard Grafton, who, in 1537, was the first publisher of the Bible in England. I say in England, because the first Bible, known as Coverdale’s, and several editions of the Testament, translated by Tyndale, had been previously printed abroad in secrecy. Grafton’s first edition of the Bible was a reprint of Coverdale and Tyndale’s translation, with slight alterations, by one who assumed the name of Thomas Matthew, but whose real name was John Rogers, then Prebendary of St. Paul’s, and afterward burned as a heretic in Smithfield. Even this was printed secretly abroad, nobody yet knows where, and did not have Grafton’s name attached to it till the King had granted him a license under the privy seal. Though this year, 1537, has by the annalists of the Bible been called the first year of triumph, on account of the King’s license, yet Bibles were still apt to be dangerous things to all concerned; and what was permitted one day was not unlikely, by a change in religion or policy, to be interdicted the next with severe visitations.

Although Henry VIII had recently completed his breach with Rome and been excommunicated, he alternately punished the religious movements of Protestants and Catholics, according to his caprice; and it was but a few years previously that the reading of the Bible had been prohibited by act of parliament, that men had been burned at the stake for having even fragments of it in their possession, and that Tyndale’s translation of the new Testament had been bought up and publicly burned (1534) by order of Cuthbert Tunstall, Bishop of London; and even as late as May, 1536, the reading of the sacred volume had been strictly forbidden.

Grafton, therefore, must have been a bold man to face the danger. Thus, in 1538, when a new edition of the Bible, commonly called the “Great Bible,” afterward published in 1539, was secretly printing in Paris at the instance of Lord Cromwell, under the superintendence of Grafton, Whitchurch, and Coverdale, the French inquisitors of the faith interfered, charging them with heresy, and they were fortunate in making their escape to England.

Shortly after the death of Caxton’s patron, Lord Cromwell, Grafton was imprisoned for the double offence of printing Matthew’s Bible and the Great Bible, notwithstanding the King’s license; and though after a while released, he was again imprisoned in the reign of Philip and Mary on account of his Protestant principles; and, after all his services to religion and literature, died in poverty in 1572.

Printing was now spreading all over England. It had already begun at Oxford in 1478 — some say earlier — at Cambridge soon after, although the first dated work is 1521; at St. Albans in 1480; York in 1509; and other places by degrees.

Printing did not reach Scotland till 1507, and then but imperfectly, and Ireland not till 1551, owing, it is said, to the jealousy with which it was regarded by the priesthood.

We will now take a rapid survey of the vast strides printing has made of late years in England, and therewith close. The principal movements have been in stereotyping, electrotyping, the improvement of presses, and the application of steam power. Stereotyping is the transfer of pages of movable type into solid metal plates, by the medium of moulds formed of plaster of Paris, papier-mâché, gutta-percha, or other substances. This art is supposed to have been invented, in or about 1725, by William Ged, a goldsmith of Edinburgh. A small capitalist, who had engaged to embark with him, withdrawing from the speculation in alarm, he accepted overtures from a Mr. William Fenner, and in 1729 came to London. Here he obtained three partners, in conjunction with whom he entered into a contract with the University of Cambridge for stereotyping Bibles and prayer-books. But the workmen, fearing that stereotyping would eventually ruin their trade, purposely made errors, and, when their masters were absent, battered the type, so that the only two prayer-books completed were suppressed by authority, and the plates destroyed. Upon this the art got into disrepute, and Ged, after much ill-treatment, returned to Edinburgh, impoverished and disheartened. Here his friends, desirous that a memorial of his art should be published, entered into a subscription to defray the expense; and a Sallust, printed in 1736, and composed and cast in the night-time to avoid the jealous opposition of the workmen, is now the principal evidence of his claim to the invention.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.