William Caxton, by common consent, is the introducer of the art of printing into England.

Continuing Early History of Printing,

our selection from Origin and Progress of Printing by Henry George Bohn published in 1857. The selection is presented in eleven easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Early History of Printing.

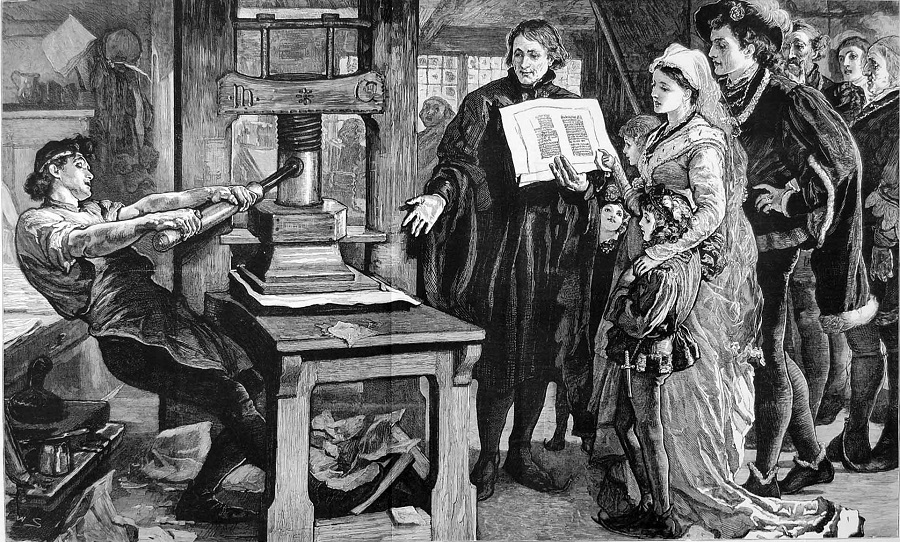

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

The accordance of the art of printing with the spirit of the times which gave it birth must be regarded as singularly providential. The Protestant Reformation in Germany was brought about by Luther’s accidentally meeting, in a monastic library, with one of Gutenberg’s printed Latin Bibles, when at the age of twenty. “A mighty change,” says Luther, “then came over me,” and all his subsequent efforts are to be attributed to that event. His recognition of the importance of printing is given in these words: “Printing is the best and highest gift, the summum et postremum donum by which God advanceth the Gospel. Thanks be to God that it hath come at last. Holy fathers now at rest would rejoice to see this day of the revealed Gospel.”

William Caxton, by common consent, is the introducer of the art of printing into England. He was born about 1422, in Kent, and received what was then thought a liberal education. His father must have been in respectable circumstances, as there was at that time a law in full force prohibiting any youth from being apprenticed to trade whose parent was not possessed of a certain rental in land. In his eighteenth year Caxton was apprenticed to Robert Large, an eminent London mercer, who in 1430 was sheriff and in 1439 Lord Mayor of London. At his death, in 1441, he bequeathed Caxton a legacy of twenty marks — a large sum in those days — and an honorable testimony to his fidelity and integrity. Soon after this the Mercers’ Company appointed him their agent in the Low Countries, in which employment he spent twenty-three years.

In 1464 he was one of two commissioners officially employed by Edward IV to negotiate a commercial treaty with Philip of Burgundy; and in 1468, when the King’s sister, Margaret of York, married Charles of Burgundy, called “the Bold,” he attached himself to their household, probably in some literary capacity, as in the next year we find him busied in translating at her request. During the greater part of this long period he was residing or travelling in the midst of the countries where the new art of printing was the great subject of interest, and would naturally take some measures to acquaint himself with it. Indeed, it has been said that he had a secret commission from Edward IV to learn the art, and to bribe some of the foreign workmen into England. Be this as it may, we know that Caxton acquired a complete knowledge of it while abroad, for he tells us so, and that he had printed at Cologne the Recueil des Histoires de Troye (or Romance History of Troy), in 1465, and in 1472 an English edition of the same, translated by himself. These two early productions are remarkable as being the first books printed in either the French or English language[26]. The English edition was sold at the Duke of Roxburghe’s sale for one thousand sixty pounds, and is now in the possession of the Duke of Devonshire.

Caxton returned to England about 1474, bringing with him presses and types, and established himself in one of the chapels of Westminster Abbey, called the Eleemosynary, Almondry, or Arm’ry, supposed to have been on the site of Henry VII’s chapel. A printer would naturally resort to the abbey for patronage, as in those days it was the head-quarters of learning as well as of religion. Before the foundation of grammar schools, there was usually a scholasticus attached to the abbeys and cathedral churches, who directed and superintended the education of the neighboring nobility and gentry. He was, besides, one of the members of the scriptorium, a large establishment within the abbey, where school and other books used to be written.

The first book Caxton printed, after he returned to England and established himself at the Almonry, is supposed to be The Game and Play of Chesse, dated 1474. But some have raised doubts whether this was printed in England, as there is no actual evidence of it. One of the arguments is that the type is exactly the same as what he had previously used at Cologne; but this is no evidence at all, as both the type and paper used in England for many years came from Cologne, and there is no doubt that Caxton brought some with him. A second edition of the book of chess, with woodcuts, was printed two or three years later, and this is generally admitted to have been printed in England.

The first book with an unmistakable imprint was his Dictes and Sayings of Philosophers, which had been translated for him by the gallant but unfortunate Lord Rivers, who was murdered in Pomfret castle by order of Richard III. The colophon of this states that it was printed in the Abbey of Westminster in 1477. He appears to have printed but one single volume upon vellum, which is The Doctrynal of Sapience, 1489, of which a copy, formerly in the King’s Library at Windsor, is now in the British Museum. This is a very interesting work as connected with Caxton, being entirely translated by himself into English verse. It is an allegorical fiction, in which the whole system of literature and science comes under consideration.

Caxton died in 1491, after having produced, within twenty years of his active career, more than fifty volumes of mark, including Chaucer, Gower, Lydgate, and his own Chronicle of England. Before Caxton’s time the youths of England were supplied with their school-books and their reading, which was necessarily very limited, by the Company of Stationers, or text-writers, who wrote and sold, by an exclusive royal privilege, the school-books then in use. These were chiefly the A B Cs, (called Absies), the Lord’s Prayer, the Creed, and the address to the Virgin Mary, called Ave Maria.

The location of these stationers was in the neighborhood of St. Paul’s Cathedral, whence arose the names Paternoster Row, Creed Lane, Amen Corner, and Ave Maria Lane. Manuscripts of a higher order, that is, in the form of books, were mostly supplied by the monks, and were scarcely accessible to any but the wealthy, from their extreme cost. Thus, a Chaucer, which may now be bought for a few shillings, then cost more than a hundred pounds; and we read of two hundred sheep and ten quarters of wheat being given for a volume of homilies.

More information here and here, and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.